Guido de Ruggiero and the Crisis of Liberalism

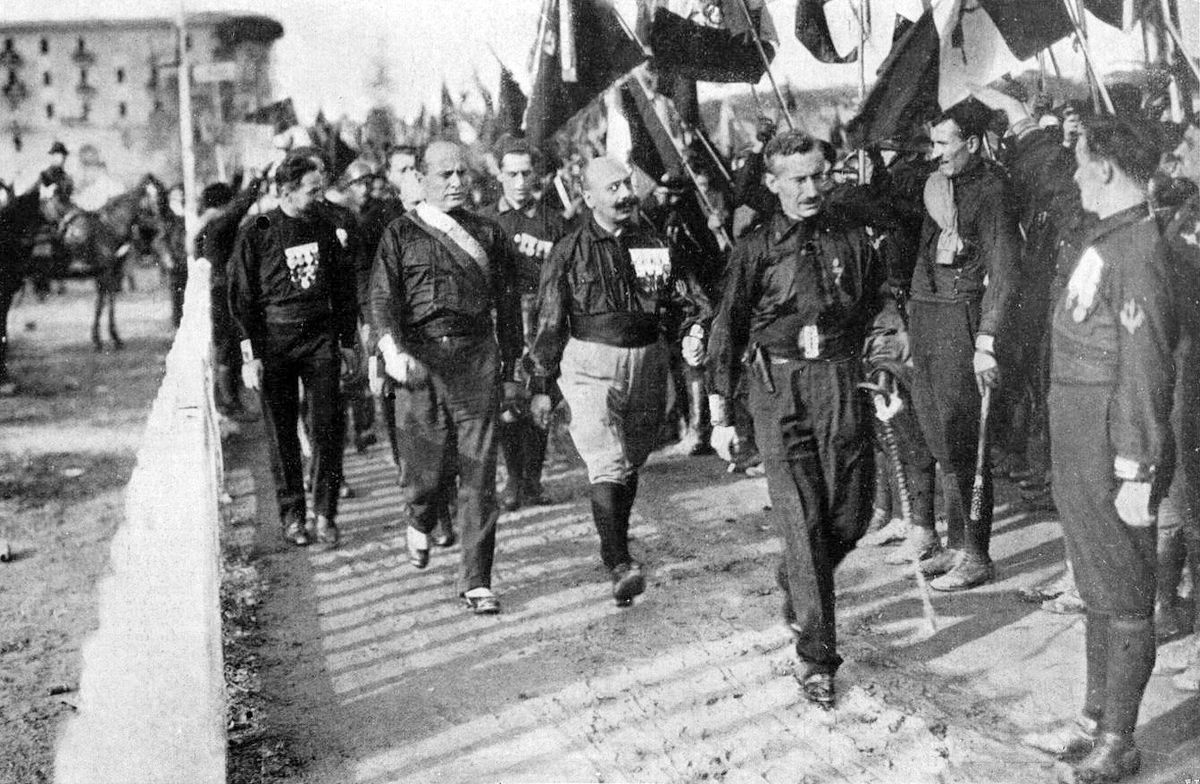

“This crisis has long been concealed by the survival of the outward forms and historical institutions created by freedom, veiling its internal decay beneath,” wrote Guido de Ruggiero ominously in his History of European Liberalism (HEL). In 1922, when de Ruggiero was an historian of philosophy, teaching at the University of Rome, he witnessed Benito Mussolini become Prime Minister after 30,000 of his paramilitary followers marched on Rome. One can only imagine that there was something both terrifying and clarifying seeing up close the rise of Mussolini and fascism. Rather than despair, de Ruggiero took a long step back and embarked on a careful and detailed history of liberalism in Europe, convinced that something in its trajectory had gone terribly wrong. In 1924—the same year that Mussolini consolidated power in a decisive and fraught election—he published his broad and deep history, covering the 17th century to the 20th, encompassing the liberalisms of Britain, France, Germany and Italy.

HEL is riveting and disturbingly relevant. The climax of de Ruggiero’s history is a detailed “diagnosis” of what ailed the liberal project. One can see in his diagnosis an extraordinary mix of idealism and insight, myopia and foresight. De Ruggiero’s diagnosis makes clear that the social classes and industries of the past—however strong their association was with the expansion of liberty—cannot long be relied on to carry forward the torch of liberal ideals. If those ideals are to persist, each generation must confront the members of the old guard that pay lip service to liberty while using the state to safeguard their power and profits. Just as de Ruggiero studied the history of liberalism in Europe to better understand contemporary threats to liberty, we might use de Ruggiero’s insights to better understand the causes and consequences of fragile commitments to liberty today.

Synthesizing an ideal liberalism

De Ruggiero’s concept of liberalism followed from his study of its history in Europe. Ideal liberalism resulted from the synthesis—here we get our first taste of de Ruggiero’s affection for the Hegelian dialectical method—of English liberalism (concrete but narrow) with French liberalism (universal but abstract). English liberalism was a concrete set of rights so narrowly construed that they are better called privileges—distinct protections for certain groups against encroachment by the monarchy or the church—and therefore “enjoyed by a minority to the detriment of the community as a whole.” French liberalism, in contrast, was embodied in the abstract assertions in the Declaration of the Rights of Man, which rightly sought to replace the privileges of the old regime with universal rights, but was “devoid of practical sanction and guarantee” and without an institutional infrastructure to guard them. Synthesis would combine and take the best of the two traditions, resulting in a liberty that was concrete, and therefore practical and defensible, and universal in its application to all members of society.

This synthesis was the conceptual foundation for de Ruggiero’s liberalism, and on this foundation he described a “liberal method” and a “liberal state” that were necessary to complete the liberal project. The liberal method was de Ruggiero’s insight that the concept of liberty only functioned with an open and optimistic view of one’s fellow humanity, or “the presupposition that … the capacity to pursue a moral end … belongs to every man … and is not the privilege of the few.” The liberal state had a similarly open and universal character, describing the moral obligations of governing as distinct from the organizational function of a political party. “[A] government, even if derived from one party, governs for all and in view of the interests of all. It is obliged … to consider fairly the motives of its opponents and to reconcile these views with its own. Care for the interest of the minority is the most strictly liberal of its tasks.”

De Ruggiero’s view of the essential rights that would be protected in the liberal state was comprehensive: “freedom of conscience is considered essential …this implies religious liberty and liberty of thought” as well as “freedom to express and communicate his own thought, personal security against all oppression, free movement, economic liberty, juridical equality, and property.” Property rights here are not absolute because “if property is essential to the development of man’s natural liberty, it ought not be enjoyed exclusively by a few, as an odious privilege.” Moreover, in keeping with earlier traditions, all of these rights were natural and inherent, but ultimately safeguarded and formalized in society, becoming civil rights.

The crisis of liberalism

Well before World War II, de Ruggiero recognized that liberalism was in a profound crisis, the economic and political foundations of the liberal state greatly weakened, with more than a few disturbing echoes in our own time. The liberal ideology of the bourgeoisie and energy of the Industrial Revolution had given way to an industrial oligarchy, exploiting state power for the protection of its own profits. The discipline of “competition was replaced by the solidarity of the trust” and “the industrial classes which formerly saw in the state something hostile … come to see it as their strongest ally, able to create prosperity for certain industries out of next to nothing.” As a result, the “industrial revolution polarized the interests of society” and “began a slow but constant erosion of the middle class whose fragments were thrown into the proletariat.”

The abandonment of liberalism by the bourgeoisie was a sign of deepening moral and political crisis. Commitment to liberalism had led the bourgeoisie to “postpone or even sacrifice its own private interest to the public good, and accept the verdict of freedom even when given against itself.” However, over time “as social competition becomes aggressive the Liberal bourgeoisie stiffens into an attitude of defense to preserve its own private interests” and laws, “instead of serving to decide conflict, become the object of contention; from the safeguard of all parties alike, they become the weapon of faction.” De Ruggiero saw the conflation of political parties with economic class interests as one of the most serious threats to liberal governing, “… if the political world is to repeat in its own parties the divisions of classes, it can only provide a field for disastrous reduplication of the social conflict.” When the bourgeoisie began to think of themselves not as the scions of liberty but as just another economic unit in a Darwinian struggle, their commitment to liberalism had already vanished.

Answering the ideological challenges to liberalism

In such a debilitated state, liberalism was in no condition to respond effectively to its many intellectual competitors of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. De Ruggiero believed that liberalism must not merely confront but understand and internalize these competitors, in particular socialism, democracy, and nationalism, if it would again inspire support among citizens and governors. Here de Ruggiero’s adherence to a Hegelian dialectical method is most evident. Every challenge to liberalism was just an antithesis waiting for the appropriate synthesis. This approach, while rigid to the point of being formulaic, was also the core of de Ruggiero’s optimism. If synthesis was always possible, there would invariably be a constructive compromise to address every intellectual and practical obstacle to the liberal method. Carrying out this synthesis would strengthen and enrich the liberal method itself. It was no coincidence that each challenger to liberalism contained some seed of liberal ideas that could be harnessed and cultivated.

The unfettered union of socialism and democracy was for de Ruggiero a serious and perennial threat to liberalism: “the omnipotence of the majority is the practical corollary of democracy; and the formal respect for the rights of minorities loses all effectual sanction” while socialists “dreamed of a moribund and stagnant uniformity.” Rather than act as a check against elites, de Ruggiero argued that majoritarian control over property would inflame society’s worst instincts and encourage a demagogic political class that only claimed to speak for the majority. In both of these powerful ideas, however, de Ruggiero found much for liberalism to learn and synthesize. “No one can deny that the principles lying at the root of the democratic idea are a logical development of the ideal premises of modern Liberalism” and “the present position of the working man, as a man and not a mere machine or commodity, is largely due to Socialism, which thus appears to be the greatest movement of human emancipation since the French Revolution.”

Nationalism was perhaps the most imminent challenge to liberty in de Ruggiero’s Europe of 1924. Nations, in his mind, could be “creatures of liberty” because a shared history under an illegitimate or despotic leader “impels national feeling to assert itself against the oppressor.” National solidarity could break down old societal barriers, thus promoting more widely held rights. However, “there is in the personality of a nation something … more questionable” and “the very vitality of the new National State … has made them increasingly dissatisfied with national boundaries and anxious to expand.” This wreckless nationalism was dangerous not merely to neighboring countries: when nationalism takes hold domestically “internal policy assumes an authoritarian character in order to subject the entire nation to the will of a handful of politicians.”

Passing the torch

Against an array of intellectual adversaries and a firmly established political and economic hierarchy, could anyone mount a persuasive defense of universal liberal ideals? Here de Ruggiero found much hope for the future. “Not all industries are equally concerned in the rigid solidarity of the industrial system” and “they form a strong center of resistance for Liberalism and the tradition of free trade.” That is, “the centrifugal force of specialized production reintroduces a rich variety … whose importance consists in the autonomy of their initiative and the originality of their various products” and “here there is a reservoir of liberalism for the future.”

Just as important, there was a new middle class, “equidistant from the great capitalistic bourgeoisie and the proletariat, due to the ever-increasing specialization of industrial and agricultural activity.” This class was composed of “the innumerable branches of the professional and commercial classes and the aristocracy of labor.” They view themselves “not only as producers … but also as consumers, in which capacity they are interested in limiting the interference of the great industrial and financial organizations in the economic policy of the state” and “promoting internal and international competition.” In an alliance of these industries and social classes de Ruggiero expected liberalism would find its much needed advocates and defenders.

De Ruggiero admirably practiced this advocacy in his own life and writings. What had begun as a subtle and indirect critique of the fascist regime, and similar currents across Europe, ultimately led to his dismissal from the University of Rome, when HEL was reprinted in 1941. He also became a prominent member of the anti-fascist opposition Action Party, leading to his imprisonment in 1943 under German occupation. It is hard to know quite how to interpret de Ruggiero’s false—or at the very least premature—optimism that “the Liberal State has survived and survives…however hostile conditions may be to its manifestation” and that “freedom is triumphing over its enemies.” Regardless, there is an instructive pattern here. The nascent industries and energized social classes that once fought for the expansion of liberty will, as time passes, become corrupted by the temptation to use state power for their own advantage. This advantage will be sustained by nostalgic appeals to increasingly distant victories. Meanwhile, “the survival of the outward forms and historical institutions created by freedom” induces a complacency that prevents an honest assessment of contemporary challenges and blinds intellectuals to the need for a reinvigorated liberalism.

In 1944, after Allied victory, de Ruggiero became Italy’s Minister of Education, before returning again to the University of Rome, first as Rector and then once again as a mere professor. His work makes clear that for liberty to persist, new industries and new social groups must articulate and practice new forms of liberalism in place of the stale and anachronistic liberty of their ancestors. De Ruggiero viewed this as an opportunity for freedom to create “for itself new paths, new forms, and new institutions.” An organic process, at work on the streets, in households and neighborhoods, is essential to liberty because “[a] permanent influence of liberalism on democracy is possible only if its action begins from below, from the humble experiences of association and organization, rising by degrees to the wider manifestations of social life.”

Featured image is the March on Rome 1922