House Hoarders

Our media is obsessed with wealth inequality. From Succession to The White Lotus, with Parasite and Triangle of Sadness taking big-screen accolades, the comings and goings of the ultra-rich are of mass interest.

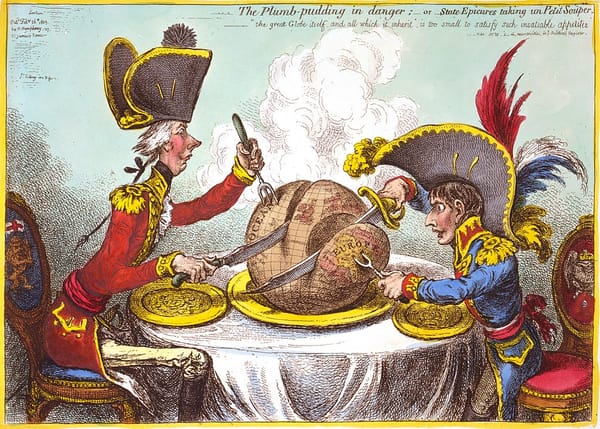

This, of course, coincides with a surge in wealth inequality. The share of the pie going to the fattest cats is growing, while everyone else has the same or less. There are many causes of this: tax law, regulation, antitrust enforcement, the financial industry, one could name basically every area of policy. But the one that receives the least attention, unfortunately, is housing—and it is one of the most important.

An owner’s world

Income and wealth inequality has soared in the last four decades, globally as well, and interest in it has matched its astronomical rise in the last decade. For most people, income comes from the wages they earn, with perhaps a little bit of savings or investing for those comfortable and prudent enough. Meanwhile, the income of the rich and especially ultra rich come mostly from what they own. Thomas Piketty’s now-legendary Capital in the Twenty-First Century pointed to this fact, and found that the share going to owners was growing simply because the value of what they owned (companies, stocks, houses, art) grew faster than the total wealth and income the economy produced. There was disagreement over his facts, but the question was not if inequality rose, but how much it did.

The search for the causes of this issue thus began, and something that was not noted very often was how Piketty defined capital (i.e. assets owned)—he included housing. As a matter of fact, the share of the pie going to capital not including residential homes remained basically flat, and the bulk of the difference can be attributed to the surging values of land. This means that the rise in inequality can be attributed to increasingly unequal homeownership.

Housing is the core component of middle and even upper middle class wealth, so the distribution of its ownership has massive implications for inequality. Similarly, higher rents represent a transfer from (poor) renters to (rich) landlords. Surging housing costs across the developed world heightened inequality—increasing the value of assets owned by a few, while the many lack access to the same ladder. In fact, in most of the developed world, homeownership inequality accounts for the vast majority of overall wealth inequality. Of course, given preexisting income disparities between white and non-white people, and due to specifically directed government policy, this has also exacerbated the racial wealth gap. This exacerbates the issue that cities were built with racist and sexist intent, most of the time, with dire consequences for equality.

Why did the cost of housing increase so much? The long and short of it is that most of the developed world stopped building enough of it, public or private. Building more housing gives tenants more options and therefore reduces the power of landlords to raise rents (or to discriminate)—even if these are units geared for the highest income buyers and renters. Without high-end units to rent or buy, high-income residents simply turn around and compete with “regular” people for “regular” units. To not get lost in the weeds of a complicated and technical topic: more housing = lower rents. The relationship of inequality with supply restrictions is particularly stark: the lower the supply, the higher the inequality.

Pulling away the ladder

There is a relationship between inequality and socioeconomic mobility known as “The Great Gatsby Curve,” which states that the more unequal the distribution of resources in a society, the fewer the opportunities of its poorer members to improve their (relative) situation. Socioeconomic mobility is the ability of lower-earning children to ascend the ranks of society—the likelier this is, the more mobile the society. In the United States, for instance, socioeconomic mobility is low (and lower than peer countries), has gone down over time, and is lower for non-whites than whites.

The first cause of im/mobility to consider is economic growth: in a growing economy, there are more opportunities up for grabs, and more openings for the talented to make their mark. By contrast, in Latin America, equal countries with low growth are just as immobile as highly unequal societies. Worse, societies and economies with slower growth tend to be more unequal overall, per Piketty’s own famous work. A shortage of housing harms economic growth, by restricting the opportunities of highly skilled individuals from participating in the most productive sectors of the economy—think of all the “geeks” who had to leave San Francisco due to high rents and could not contribute to tech. This means lower productivity in companies, and lower innovation overall—these effects are so large that the Blitz during World War Two helped the British economy by allowing more housing to be built in its main cities. Our unwillingness to build enough housing is strangling both economic growth and social mobility.

The mechanics behind the relationship between low social mobility and high inequality (or vice-versa) are complex, but one of the main elements is education: parents with more resources can devote more money and attention to their children’s education, improving their lot in life. Education, from kindergarten to college, greatly improves lifetime earnings. But higher education is increasingly acting as a stratifier, not a leveler—because of entry. The highly educated, in fact, make up one of the richest and least downwardly mobile groups in society—the true “villains” are the people you can find in The White Lotus, not in Succession. Lawyers, doctors, and dentists are overrepresented in the top 1%—just ask Chris Rock—through lobbying to restrict entry into their profession.

Education, however, is highly tied to location. In the United States, for instance, where you live determines the quality of your education to a staggering degree—the most economically segregated locations tend to have the highest quality schools. In fact, moving from “poor” to “rich” areas (or from small to big cities) markedly improves incomes, and the younger, the bigger the effects. Part of this is that lower income areas have a number of issues, but a big part is simply that some locations are better for certain skillsets than others—better jobs, better amenities, better networks. The poorest US states stopped catching up with the rich ones because people could not move elsewhere. Such migration raises incomes for those who leave—and for those left behind.

The importance of location is also influenced by social networks: more inter-class friendships are strongly associated with higher economic mobility. This might explain one of the more baffling facts about economic mobility: the only group to consistently have it, in the United States, are the children of immigrants—and it’s not attributable to education. Given that it’s true for immigrants all over the world, and varies within regions, it can’t really be “culture” either. An option, thus, is that immigrants tend to cluster in certain industries and in certain locations—meaning they do have the kind of “interclass networks” everyone else lacks.

The role of housing for reducing the ability of the poorest families to improve their standing cannot be overstated: firstly, unequal access to homeownership results in an unequal distribution of wealth. But given how growing up in affluent communities, or at least communities with well-off members, allows for better chances of rising up in the income ladder, this also reduces future possibilities of increasing wealth—making the situation worse. Factor in how location, especially in the United States, determines the quality of education you receive, and your future opportunities to attend college, and the situation only worsens. Whoever controls housing controls access to most forms of economic participation.

Beware of the homevoters

If housing scarcity is benefitting the rich at the expense of everyone else, why have politicians not tackled it? There is a powerful coalition behind more housing: business owners who want more employees, renters, parents, progressives, and of course, real estate developers. But this group, called the “growth machine”, is facing off against another entrenched interest group: the “homevoters”.

The latter group is made up of homeowners who, for some reason or another, want to prevent more housing from being added to their neighborhoods—or to any other, for that matter. Sometimes, the reason is that they want to keep the “character of the area” similar to what it currently is (which might or might not have ulterior, let’s say, motives), and sometimes the reason is just plain greed: wanting to keep their property values up. This attitude is known as NIMBYism, short for “Not In My Back Yard”, and it even affects people who do actually want to build more—just not here, where I live.

In economics, NIMBY homevoters are an example of what’s called rent-seeking behavior: individuals who demand the government benefit them at the expense of society. This works simply because they ask for measures that have widespread costs but concentrated benefits—there is a very large group of harmed parties, who don’t suffer directly much, and a small and influential group that greatly benefits. The rent seekers simply care more. But because these groups are small and influential, and the harmed parties are widespread and more distracted, they can block progress until their heart’s content—reducing economic growth. Over time, rent seeking can cause economic backwardness—if elites can marshall themselves into these fights, they can consistently flex their muscles and prevent progress.

In reality, the NIMBYs persistently beat out the growth machine—they care more, they are more organized, and they are wealthy enough to promote policies dedicated to a single cause. This is largely caused by the undemocratic structure by which housing policy is set: having the public directly comment on it. Access to these meetings is not equitable: the majority of participants are homeowners (who also are more likely to vote in local elections in general), and they are richer, whiter, and older than renters.

These citizens are, of course, exercising their right to participate in a public process—one designed to give them the biggest say and which has an unsavory history and associations. But the reality is that allowing an angry mob to shout down anything counter to their tastes and interests is just not socially desirable—and it results in heightened inequality by restricting the amount of housing available.

Conclusion

Housing reaches every aspect of our lives—and inequality is no different. By allowing the already rich to prevent the value of their investments from ever going down, the developed world has sleepwalked into an unenviable situation: one of stratified incomes, reduced opportunities, and worse outcomes for everyone. The clear solution is eliminating the rules that prevent more housing from being built, and replace them with ones that increase, not decrease, the ability of those at the bottom to rise to the top.

Featured Image is Entrance to a guarded gated community by Parihav