Lessons for the Left: Achieving Our Country Revisited

If we look for people who made no mistakes, who were always on the right side, who never apologized for tyrants or unjust wars, we shall have few heroes and heroines.

“National pride is to countries what self-respect is to individuals: a necessary condition for self-improvement,” Richard Rorty wrote. “Too much national pride can produce bellicosity and imperialism, just as excessive self-respect can produce arrogance.”

This was—and still might be—a tough pill for leftists to swallow as we stumble into the third decade of the century. But Rorty pulled no punches in the his first Massey lecture, “American National Pride: Whitman and Dewey,” which would later become Achieving Our Country, a book that argues that the U.S. once had a genuine social democratic left but has since been eclipsed by a new kind of left that he sees as having exhausted its political potential. This old, social democratic left “collapsed during the late sixties under the burden of the conflagration surrounding the Vietnam War” and was replaced by one that thought the only way forward was a “complete dismantling of the ‘system.’”

“The difference,” Rorty says, “between early twentieth-century leftist intellectuals and the majority of their contemporary counterparts is the difference between agents and spectators,” between what he calls the reformist left of the first half of the 20th century and the cultural left which came to dominate not the streets but the academy after the 1960s. This shift on the left is ultimately the story of Achieving Our Country.

The necessity of national pride

As Rorty sees it, one of the driving forces behind this change on the left was its self-conscious shift from national pride to national disgust. Whereas earlier—in the first two-thirds of the century, before the Vietnam War—leftist writers from liberals to socialists had faith in America as a land of hope and inspiration, today “few inspiring images and stories are being proffered,” and “descriptions of what America will be like in the twenty-first century are written in tones either of self mockery or of self-disgust.” Earlier novels like The Jungle, An American Tragedy, and The Grapes of Wrath were “written in the belief that the tone of the Gettysburg Address was absolutely right,” and that it was enough for the American experiment to see itself as an attempt to “fulfill Lincoln’s hopes.” Today we see a proliferation of “novels not of social protest but rather of rueful acquiescence in the end of American hopes” in which America is thought of “as something we must hope will be replaced, as soon as possible, by something utterly different.”

An intense chauvinistic patriotism is, of course, one of the core components of the right, but a tempered kind of national pride has few avenues for expression on the left. When history does get brought up on the left, it usually gets associated with the laundry list of atrocities committed by the U.S.—the slave trade and slavery, the annihilation of Native Americans, the destruction of the environment, Vietnam. Who could be proud of a country with such a terrible past?

For Rorty, Walt Whitman and John Dewey represent two leftists who didn’t abandon hope in America; they neither denied America’s sinful past nor embraced it as unforgivable. Thus, according to Rorty, Whitman and Dewey should be praised not for their attempts to represent America accurately or offering us what we would call a history, but for their “attempts to forge a moral identity.” This point about forging a moral identity is important because it gives the reader a window into how Rorty thinks about the uses of American history, a subject he wrote precious little about in any substantial sense.

Rorty doesn’t think “that there is a nonmythological, nonideological way of telling a country’s story.” Calling something a myth requires contrasting it with something we would consider an objective, neutral telling of history, and frankly, Rorty says, “nobody knows what it would be like to try to be objective when attempting to decide what one’s country really is, what its history really means, any more than when answering the question of who one really is oneself, what one’s individual past really adds up to.”

With this rather radical view of history in hand, Rorty says that arguments about this or that version of history or this or that historical episode and its place or meaning for us—for example, the founding period—are not really about history at all, but are arguments “about which hopes to allow ourselves and which to forgo.” Once we rid ourselves of the idea that there is one, true objective history, we will see that our discussions about America’s past aren’t usually about facts—the way academic historians might talk about them—but are points raised about what direction we should head as a nation.

The debate over history has only increased in intensity since the time of Rorty’s writing: from the New York Times’s 1619 Project to the current arguments over monuments. But to Rorty’s point, we shouldn’t see these projects as concerned with getting down to rock-solid truth, but rather about “about which hopes to allow ourselves and which to forgo.”

I think Rorty would have thought the 1619 Project’s goal—to “reframe the country’s history, understanding 1619 as our true founding” and to place “the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative”—regrettable. Not because he shared any special attachment to 1776 or harbored some deep chauvinism, but because placing our country’s founding on an irreversible and seemingly unforgivable sin rather than a statement of hope is to give in to the kind of “fashionable hopelessness” Rorty saw as endemic of the post-sixties left. In one of the last essays he wrote—and a succinct summary of the historical project he was engaged in—Rorty quipped that “our country has a history, but not a nature.” To say that our founding date should be moved to 1619 when the first Africans were forcibly ripped from their homes and brought to our shores in order to argue that slavery is really the core of our history is to admit that our country has a nature and that nature is largely made up of horrifying episodes—and is thus beyond redemption. But slavery isn’t the core anymore than freedom is.

At some point, according to one story, historians stopped writing about national histories to focus on both smaller and bigger things—more niche and local histories as well as global ones. Some in this movement saw its “principal task” as debunking the “Lincolnesque story of America as a land of freedom,” focusing on, for example, the experience of Native Americans, slaves, and women in the founding period. These much-needed histories were not necessarily the efforts of nefarious historians—far from it—but they were nonetheless used to dislodge us from the collective fiction that our founders were all freedom-loving heroes that deserved our unending worship and praise and that United States was and is a beacon of freedom and liberty, that “city upon a hill.”

The 1619 Project and other projects like it follow this same debunking tradition and there are no signs of it letting up. But Rorty, in as late as 2007, thought “the work of demystification [had] been accomplished,” and “that we do not need to do it again and again.”[1] Leftists today still don’t think of themselves as Baldwin, Whitman, and Dewey thought of themselves, “as American patriots, hoping to achieve their country.”[2]

Rorty’s point is that the post-Vietnam left is so steeped in the negative episodes of our history that they come to think we, as a nation and people, are beyond redemption. But the kind of pride Rorty wants us to have, some on the left will respond, is simply incompatible “with remembering that we expanded our boundaries by massacring the tribes which blocked our way that we broke the word we had pledged in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, and that we caused the death of a million Vietnamese out of sheer macho arrogance.”

But Whitman and Dewey didn’t think America was beyond redemption. That even with the scale of justice heavily tilted to one side, it was still possible to have pride in one’s country. They thought there were “many things that should chasten and temper such pride, but that nothing a nation has done should make it impossible for a constitutional democracy to regain self-respect.” Rorty extends the metaphor from the very first line of this lecture—that “national pride is to countries what self-respect is to individuals”—when he says that there are “some acts we believe we ought to die rather than commit.” But, he says, let’s say we find ourselves having committed that act anyway. At this point, “one’s choices are suicide, a life of bottomless self-disgust, and an attempt to live so as never to do such a thing again.” Rorty thinks the current left wavers somewhere between the first two options. Having surveyed the nearly endless list of past atrocities, the left has become “a spectatorial, disgusted, mocking Left” which “leads them to step back from their country and, as they say, ‘theorize’ it. It leads them to … give cultural politics preference over real politics, and to mock the very idea that democratic institutions might once again be made to serve social justice.”

Dewey, Rorty says, recommends that we grab ahold of the third option. “He thinks you should remain an agent, rather than either committing suicide or becoming a horrified spectator of your own past. He regards self-loathing as a luxury which agents—either individuals or nations—cannot afford.” Rorty claims that the left has given into self-loathing and a kind of fashionable hopelessness that we as a nation and the left as a political force just can’t afford.

For Rorty, Whitman and Dewey represent two figures who never lost the faith in America—specifically, American democracy. Both believed that the United States was very much unlike Europe in that it was “the first country founded in the hope of a new kind of human fraternity, it would be the place where the promise of the ages would first be realized.”

For both Whitman and Dewey, the terms “America” and “democracy” are shorthand for a new conception of what it is to be human—a conception which has no room for obedience to a nonhuman authority, and in which nothing save freely achieved consensus among human beings has any authority at all.

Following Whitman’s line that democracy “is a great word whose history … remains unwritten, because that history has yet to be enacted,” Rorty’s story at the end of the first lecture takes a turn toward philosophy. This story isn’t complicated but it’s unnecessary to spell out at length here. What’s important is that Rorty thought Hegel and Dewey can help us see that hope for “the contingent future” was preferable to “knowledge of the antecedently real;” that we should “look forward rather than upward.” Progress, then, becomes defined not by “our increased proximity to a goal,” but “as a matter of solving more problems” and “the extent to which we have made ourselves better than we were in the past.”

“The only sin,” Emerson said, “is limitation.” This is a nice way of summing up Rorty’s point that the only thing we should find unforgivable is the abandonment of hope. Rorty exposed hidden forms of authority in our lives—be it God, History, or Truth—and taught us to be less anxious about them—whether we were disappointing, falling away, or fulfilling them. History doesn’t hang over our heads like a dark cloud anymore than God does. To say otherwise, to think we have something to answer to besides the “intersubjective consensus among human beings,” is to not be in full control of one’s life.

In other words, hope for a better future should replace knowledge as the principal political task. It should replace the tired task of trying to get down to the way things really are or worrying about whether we as a nation are actually racist or actually something else entirely. Whitman and Dewey “wanted to put hope for a casteless and classless America in the place traditionally occupied by knowledge of the will of God,” and wanted “the struggle for social justice to be the country’s animating principle, the nation’s soul.” And we cannot do this unless we have some semblance of pride in our country.

Marxists, liberals, and the decline of the reformist left

Rorty’s second lecture, “The Eclipse of the Reformist Left,” begins with a critique of Marxism. Rorty thinks Marxism “was not only a catastrophe for all the countries in which Marxists took power, but a disaster for the reformist Left in all the countries in which they did not.” Rorty thinks that the purity Marxism demanded drove a wedge between reformist leftists—those who “struggled within the framework of constitutional democracy to protect the weak from the strong”—and what was coming to be known as the real left: the pure left, untainted by unseemly alliances and compromising ideologies.

Rorty thinks we need to abandon the Marxist interpretation of the sixties and replace it with one that better appreciates the accomplishments of the old reformist left. This Marxist history, Rorty says, divided the left into Marxists, who wanted to overthrow capitalism, and everybody else on the left. If you didn’t want to overthrow capitalism, this interpretation went, you were labeled a “wimpy liberal” and “a self-deceiving bourgeois reformer,” which covered everyone from “the people who administered the New Deal” to “those whom Kennedy brought from Harvard to the White House in 1961.” Rorty thinks the distinctions between leftists and liberals drawn by Marxists and radicals did little more than “clutter up our vocabulary” and cause unnecessary friction between people who would otherwise agree about what kinds of policy reforms were needed.

According to Rorty, Christopher Lasch was one such intellectual who provided the force behind this Marxist interpretation even if Lasch would later repudiate most of his Marxist tendencies. At the time, though, Lasch “thought that a movement which is not mass-based must somehow be a fraud and that top-down initiatives are automatically suspect. This belief echoes the Marxist cult of the proletariat, the belief that there is virtue only among the oppressed.” In one fell swoop, Lasch condemned the early reformists’ efforts to help the poor and oppressed as elitist, insincere, and ultimately bourgeois. Thus the post-sixties left came to be seen as the real left, “or at least the only ones who had not sold out.”

The language this ‘real’ left employed was tinged with words like empire rather than community; sin instead of hope; and, ultimately, revolution rather than piecemeal progress. Vietnam, as mentioned earlier, went a long way in moving the left away from thinking America was fixable to thinking it an evil empire beyond redemption. But Rorty thinks a reconciliation between the old, reformist left and new left is possible and that it begins with acknowledging all the good this new, post-sixties left accomplished, a theme he will return to in his third lecture.

It may have saved our country from becoming a garrison state. Without the widespread and continued civil disobedience conducted by the New Left, we might still be sending our young people off to kill Vietnamese, rather than expanding our overseas markets by bribing kleptocratic Communists in Ho Chi Minh City. Without the storm that broke on the campuses after the invasion of Cambodia, we might now be fighting in the farther reaches of Asia. For suppose that no young Americans had protested—that all the young men had dutifully trotted off, year after year after year, to be killed in the name of anti-Communism. Can we be so sure that the war’s mere unwinnability would have been enough to persuade our government to make peace?

Rorty thinks that even in light of the new left’s unthinking disparagement of the old left, the United States is much better because of their “rage which rumbled through the country between 1964 and 1972.” This rage, he says, was “perfectly justified.”

Rorty proposes that we consider left anyone who was “feared and hated by the Right.” Although he admits that the Communist Party of the United States did some good things like whip together a few good picket lines, on the whole, “the most enduring effects of its activities were the careers of men like Martin Dies, Richard Nixon, and Joseph McCarthy,” which gave anticommunism—and most importantly for Rorty’s story anticommunist liberals—a bad name. Yet Rorty thinks liberals should stop excoriating Marxists for leaving the party so late, and Marxists should stop excoriating liberals for seeing the disaster that was Vietnam too late. A hundred years from now, Rorty says,

Howe and Galbraith, Harrington and Schlesinger, Wilson and Debs, Jane Addams and Angela Davis, Felix Frankfurter and John L. Lewis, W. E. B. Du Bois and Eleanor Roosevelt, Robert Reich and Jesse Jackson, will all be remembered for having advanced the cause of social justice. They will all be seen as having been “on the Left.” The difference between these people and men like Calvin Coolidge, Irving Babbitt, T. S. Eliot, Robert Taft, and William Buckley will be far clearer than any of the quarrels which once divided them among themselves. Whatever mistakes they made, these people will deserve, as Coolidge and Buckley never will, the praise with which Jonathan Swift ended his own epitaph: “Imitate him if you can; he served human liberty.”

Rorty is confident that without the dangerous distraction that was Marxism and Leninism the ideals of social democracy and economic justice would have nonetheless flourished in the 20th century since these ideals “long antedated” these schools of thought anyway. He cites Herbert Croly’s The Promise of American Life—the “best-known manifesto of the Progressive Era”—as proof of this.

In his book Croly urges Americans to develop “a dominant and constructive national purpose” and says that “a more highly socialized democracy is the only practicable substitute on the part of convinced democrats for an excessively individualized democracy.” Here Croly is essentially calling for the redistribution of wealth, which Rorty sees as clear evidence that Americans, and American leftists in particular, didn’t need Marx to tell about the need to spread the wealth around or “tell us that the state was often little more than the executive committee of the rich and powerful.” It’s already abundantly clear in Croly and a number of other Progressive Era writers including Dewey. It didn’t take Marx to know how the economy worked and that we needed to unionize and organize the workers. “Cobbet knew that, I’m not sure that the Roman plebes didn’t know that. I think the idea that Marx burst upon an astonished world with the thought that the rich were ripping off the poor is weird.”[3]

Ultimately the reconciliation Rorty wants to see comes from a deep understanding that “both the New Left and the American labor movement look very good indeed … when compared with the ruthless greed, systematic corruption, and cynical deceit of the military-industrial establishment” and with conservatives who make their careers out of censuring the left but themselves “have no remedies to propose either for American sadism or for American selfishness.” Ultimately, Rorty says closing out the second lecture,

The heirs of that older Left should stop reminding themselves of the stupid and self-destructive things the New Left did and said toward the end of that decade. Those who are nostalgic for the Sixties should stop reminding themselves that Schlesinger lied about the Bay of Pigs and that Hook voted for Nixon. All of us should take pride in a country whose historians will someday honor the achievements of both of these Lefts.

The rise of the cultural left

Rorty begins his third lecture, “A Cultural Left,” by once more praising the old reformist left but hastens to add that “most of the direct beneficiaries of its initiatives were white males.” African-Americans, women (after they got the right to vote), and other minorities were mostly left out of the conversation. “Blissfully unaware” of the lynching and segregation in other parts of the country, Northern leftists of the first two-thirds of the century still largely treated the non-white, non-male, and non-straight population with derision and contempt. “From the point of view of today’s Left,” Rorty says, “the pre-Sixties Left may seem as callous about the needs of oppressed groups as was the nation as a whole.”

Nonetheless, the pre-Sixties reformist left was operating under the belief that once economic inequality was taken care of, prejudice and discrimination would largely disappear—the latter were just byproducts of the former.[4] Rorty sees this exclusive focus on the economic to be “misguided,” and that the new left was right to say that discrimination and prejudice could not be reduced to economic inequality; that regardless of one’s economic situation there seems to be a “delicious pleasure to be had from creating a class of putative inferiors and then humiliating individual members of that class.”

But this correct diagnosis that prejudice ran deeper than economics also spawned what Rorty refers to as the cultural left, a left he would later distinguish from the new left at the behest of critics who claimed, rightly I think, that not everyone went headlong into the culture wars and forgot about economic issues like many on the cultural left did.[5] In any case the cultural left, he says, partially swapped Freud for Marx and started to focus less on economic issues or where the money was flowing and more on the “‘politics of difference’ or ‘of identity’ or ‘of recognition.’”

The cultural left, Rorty goes on, “thinks more about stigma than about money, more about deep and hidden psychosexual motivations than about shallow and evident greed.” To put the difference squarely, the “reformist Left thinks more about laws that need to be passed than about a culture that needs to be changed.” Rather than studying political economy or laws or institutional structures, required reading on the left during the ’60s became the “apocalyptic French and German philosophy” of Derrida, Lacan, Foucault, and Freud. With this curriculum in hand, the language of reform was dealt its final blow since “the very vocabulary of liberal politics is infected with dubious presuppositions which need to be exposed.” Working within the system to change the system is hopeless.

But just as Rorty didn’t think the reformist left’s policies and strategies in the first half of the century were beyond reproach, he doesn’t think the new left’s approach bore no fruit whatsoever. He says that the progress of sentiments brought about by the new left “has made our country a far better place.” In trying to root out the sadism that pervades our culture, they made

casual infliction of humiliation…much less socially acceptable than it was during the first two-thirds of the century. The tone in which educated men talk about women, and educated whites about blacks, is very different from what it was before the Sixties. Life for homosexual Americans, beleaguered and dangerous as it still is, is better than it was before Stonewall. The adoption of attitudes which the Right sneers at as “politically correct” has made America a far more civilized society than it was thirty years ago.

Yet although we treat each other much better than in the first half of the century, there has been precious little change in institutional structure and law since the Sixties. The march of what Rorty, borrowing a term from Michael Lind, calls an “economic overclass” took advantage of the new cultural focus of leftism and has since only increased its power and wealth, while the average citizen still worries that a surprise $1,000 medical bill will send them into a financial tailspin.

This is the “dark side” to the story of the cultural left. The American left, it seemed, “could not handle more than one initiative at a time.” Economic inequality soared as social stigma for women, homosexuals, and other minority groups withered. Though the situation isn’t perfect for any of these groups, Rorty admits, “such humiliation is not as frequent as it was thirty years ago.”

The problem the new cultural left confronts at the dawn of the 21st century is globalization, just as the old reformist left was wrestling with the rising tide of industrialization at the turn of the 20th. The benefactors of this “cosmopolitan” globalization have mostly been and will continue to be the upper 25 percent (if not smaller now), while the other “75 percent of Americans will find their standard of living steadily shrinking.” Even more, if this “overclass” continues to successfully fan the flames of the culture war as a distraction from real issues like economic inequality, these trends will continue.

At this point, Rorty says, the left has two options: “The first is to insist that the inequalities between nations need to be mitigated” and that sharing the wealth of nations in the northern hemisphere with those in the southern hemisphere should be our priority. The second option “is to insist that the primary responsibility of each democratic nation-state is to its own least advantaged citizens.” Clearly these two options conflict with each other, and, Rorty goes on to say, many academic leftists of the cultural left happily reach for the first option while the second choice “comes naturally to members of trade unions, and to the marginally employed people who can most easily be recruited into right-wing populist movements.”

In a much-quoted passage after the election of Donald Trump, Rorty offers one image of what might happen at this crossroads. It is worth quoting here at length.

At that point, something will crack. The nonsuburban electorate will decide that the system has failed and start looking around for a strongman to vote for—someone willing to assure them that, once he is elected, the smug bureaucrats, tricky lawyers, overpaid bond salesmen, and postmodernist professors will no longer be calling the shots. A scenario like that of Sinclair Lewis’ novel It Can’t Happen Here may then be played out. For once such a strongman takes office, nobody can predict what will happen. In 1932, most of the predictions made about what would happen if Hindenburg named Hitler chancellor were wildly overoptimistic.

One thing that is very likely to happen is that the gains made in the past forty years by black and brown Americans, and by homosexuals, will be wiped out. Jocular contempt for women will come back into fashion… All the sadism which the academic Left has tried to make unacceptable to its students will come flooding back. All the resentment which badly educated Americans feel about having their manners dictated to them by college graduates will find an outlet.

In the wake of this, people will begin to ask: Where was the left? Why could they not speak to the rage of the labor unions and unorganized unskilled workers in the same way that the reformist left did in the early years of the 20th century (while duly noting who was left out of that conversation)?

To avoid this “crack,” Rorty suggests that the left drop its philosophy habit, “stop thinking up ever more abstract and abusive names for ‘the system,’” and “begin to form alliances with people outside the academy, and, specifically, with the labor unions.” Part of this strategy, as Rorty mentions in his first lecture, will require the left dropping its deep-seated cynicism about America and its past. Outside of academia, in the real world, people, Rorty says, “still want to feel patriotic” and “want to feel part of a nation which can take control of its destiny and make itself a better place.” Until the left tries to build broader coalitions and alliances with other groups, laws will stay the same and the overclass will continue to make all the decisions—and money.

In order to build this broad leftist coalition, it will also be necessary for a vast array of people to put their identities in the back seat—at least when it comes to national politics. It is perfectly reasonable to “take pride in being black or gay…but insofar as this pride prevents someone from also taking pride in being an American citizen, from thinking of his or her country as capable of reform, or from being able to join with straights or whites in reformist initiatives, it is a political disaster.” Put another way, one’s rightful indignation at the past and continuing victimization of one’s identity group cannot prevent various leftist coalitions from getting together to accomplish larger goals. This includes, of course, the white working class, which has, for reasons clearly related to identity politics, been almost entirely forgotten. Rorty also seems to suggest that leftists should even go so far as to seek out alliances with otherwise unseemly or sketchy groups in order to get certain laws and policies passed—something, admittedly, that seems further and further from the realm of the possible today.

While no doubt a leftist faux pas today, Rorty’s mentioning of the white working class was not an expression of sympathy for the plight of white people or men’s rights. He just thought that in order to build an effective leftist coalition one needed to appeal to the sentiments of those who make up a considerable amount of the population—and have legitimate complaints too. Part of appealing to this broad group of people requires, as mentioned earlier, ditching or at least tempering the historical “debunking” projects. “Unless the left wraps itself in the flag,” Rorty said, the left “hasn’t got a chance of practicing a majoritarian politics.” But Rorty acknowledged the double-edged sword of this project and we seem to experiencing the same kind of tensions today.

Rorty thought it was necessary for the left to split its attention: to give half of their attention to race and gender issues and the other half to economic ones. But he was well aware of the tensions involved with a schizophrenic approach. He knew an exclusive focus on the former, race and gender, would lead to losing the white working class—who for all intents and purposes are in the same economic situation as everybody else in the bottom 75%—and focusing on the latter, class, would blind us to the ways that race and gender mix with class in terrible, often more oppressive, ways. The danger with focusing solely on class, in other words, is that African-Americans will feel neglected, and “the danger of the academy’s concentration on race and gender is that white workers think they were being neglected by the academy” and “the white workers are being neglected.” It’s a lose-lose.

Perhaps there’s no way to cut this Gordian Knot, but denying it exists certainly makes the problem worse. Rorty thought that proposing broad policies that relieve suffering was all the left needed to do—never mind whether there was some grand, theoretical integration behind all of them. And never mind whether one of those policies benefited more working-class whites than working-class blacks; the response shouldn’t be to denigrate or demean that program as racist but rather to simply propose another that aimed to benefit more working-class blacks. “I don’t see why there shouldn’t be sixteen initiatives, each of which in one way or another might relieve some suffering, and no overall theoretical integration,” Rorty said.[6]

Ultimately, Rorty isn’t nostalgic but conciliatory. He pinpoints what he sees as the pitfalls and dead ends of a range of leftist attitudes, from the reformist left’s inattention to the harms inflicted on minorities, to the cultural left’s inattention to the fact that most people, minorities included, would much rather have a better economic situation than have their ‘otherness’ recognized by people of different groups. Achieving Our Country is a good mirror for those on the left to hold up every now again and ask themselves, “What have we left out? What do we ultimately want to accomplish? Do we want to be politically effective or intellectually pure?” Rorty thought demands for intellectual purity would be the end of the left having any influence whatsoever and would only serve to drive a wedge between those who who might otherwise join the cause. Surveying the fault lines today, one cannot help but think Rorty’s fears not only have come true but the situation has worsened further.

Rorty’s reminder to the left is twofold: remember who the real enemy is—those who “have no remedies to propose either for American sadism or for American selfishness”—and don’t give up hoping that America can one day live up to its high-minded ideals. Indeed, that hope is all we have.

I have been arguing that the appropriate response to such observations is that we Americans should not take the point of view of a detached cosmopolitan spectator. We should face up to unpleasant truths about ourselves, but we should not take those truths to be the last word about our chances for happiness, or about our national character. Our national character is still in the making. Few in 1897 would have predicted the Progressive Movement, the forty-hour week, Women’s Suffrage, the New Deal, the Civil Rights Movement, the successes of second-wave feminism, or the Gay Rights Movement. Nobody in 1997 can know that America will not, in the course of the next century, witness even greater moral progress … As long as we have a functioning political Left, we still have a chance to achieve our country, to make it the country of Whitman’s and Dewey’s dreams.

[1] “The Unpredictable American Empire,” Richard Rorty

[2] Against Bosses, Against Oligarchies: A Conversation with Richard Rorty, Kent Puckett, Derek Nystrom, Richard Rorty

[3] Against Bosses, Against Oligarchies: A Conversation with Richard Rorty, Kent Puckett, Derek Nystrom, Richard Rorty

[4] You can see this pretty explicitly in the writings of John Dewey who some chastise for his racial blindspot. As Dewey scholar Gregory Pappas says, Dewey thought “that most racial friction does not originate out of racial prejudice; instead, racial prejudice grows out of some actual social (political or economical) tensions and antagonism that are conveniently and effectively tied to racial differences… [and that these tensions] are effectively associated, centered, and concealed behind racial differences because of other human psychological factors such as the natural antagonism toward that which is strange. The spontaneous negative reaction to the features that identify a group effectively replace and conceal the complex and contextual set of reasons for antagonism in the first place.”

[5] Rorty would later say that he didn’t intend to run all leftists together. The “Vietnam War, Watergate, and the loss of public confidence in the presidency and the government all conspired to move the student radicals into non-majoritarian politics,” and this is largely the left he had in mind. How much of the post-sixties left was made up of these student radicals and traditional leftists is still the focus of much debate. I, with Rorty, happen to think they were the majority. The evidence for this is the current leftist landscape.

[6] Against Bosses, Against Oligarchies: A Conversation with Richard Rorty, Kent Puckett, Derek Nystrom, Richard Rorty

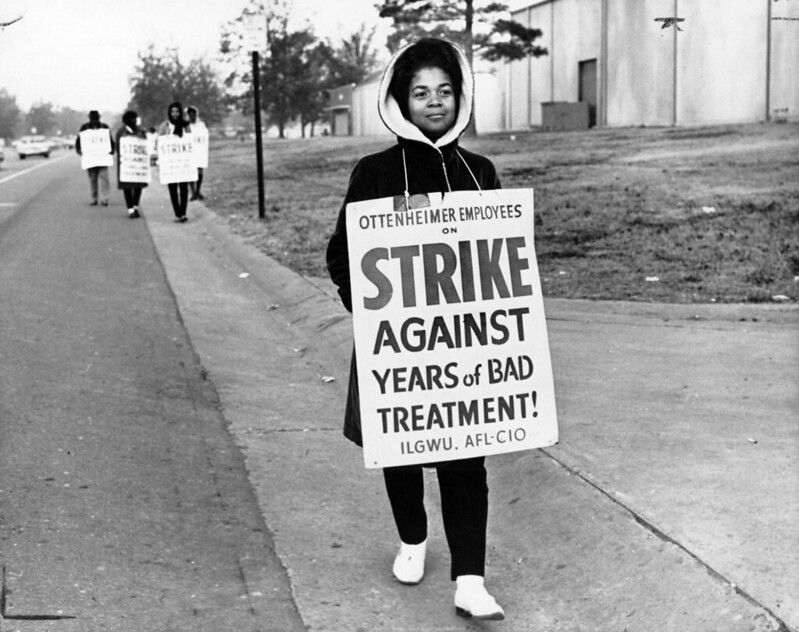

Featured Image is African American employees of Ottenheimer on strike for poor treatment