Liberalism's Positive Vision Must Be the Open Society

Liberalism is not just the mitigation of dangers. It is also an active striving towards a world that is truly free.

When The Argument launched back in August, founder and Editor-in-Chief Jerusalem Demsas lamented that “Liberals used to stand for things. But now it seems like all we do is stand against them.” Even when we are not speaking of “resistance liberals” defined by their opposition to the Trump administration, discussions of liberalism do often take on a negative quality. In describing two “origin stories” of liberalism, for example, Eric Schliesser singled out mutual toleration and taming state power as the rationales for each. Our own Paul Crider went even further, arguing that the history of liberalism can be framed around the history of its great enemies, with “MAGA, white supremacists, antifeminists, and oligarchs” being our chief enemies today.

In arguing for liberal democracy and against dictatorship, my own tendency is to emphasize a set of common problems all types of societies face in the modern world and to explain why liberalism offers the most practical tools for addressing them. While one might argue that advocating for liberal rights and representative institutions counts as standing “for things” rather than against them, it is possible to advocate in an entirely “ameliorative, mitigating spirit” as Schliesser put it.

For societies exhausted by years of open ethnic conflict, or experiencing the always precarious transition from dictatorship to democracy, that mitigating spirit may be more than enough. The practical merit of liberalism for achieving social peace under difficult conditions cannot be overstated.

Nevertheless, liberals have no need to settle for this negative vision. And indeed, even in the early days, when they were overthrowing monarchs and taking the first tentative steps towards the modern conception of human rights, liberals conceived of their success in terms of achieving a specific kind of society. As Jacob Levy put it:

A free, democratic, commercial society was thought of as more than simply a state that respected rights of various kinds. It was a society of a particular kind, one characterized by mobility, the rise and fall of elites based on achievement, and a certain fluidity.[1]

The liberal ideal must never be reduced only to the enshrining of specific rights into law, or merely accomplishing the establishment of rule of law, competitive elections, and universal enfranchisement.

To put it simply, the liberal ideal must be the achievement and defense of an open society.

The open society

Where formulations of rights and freedoms are necessarily philosophical and abstract, the open society is an empirical accomplishment, an actually existing social system. The attempt to speak of “positive liberties” among political philosophers since Isaiah Berlin gestures in this direction, but is still too grounded in the parts rather than the whole.

Where the First Amendment seeks to protect speech from government censorship, the citizen of an open society actually is free to express themselves without fear. Where some countries create legal protections for freedom of association, citizens of the open society are actually able to form, join, abandon, and dissolve voluntary associations.

It is possible, in theory, for a country that lacks strong legal protections for individual rights to nevertheless be an open society. If the government does not, in practice, behave in a heavy-handed manner, and the private norms of the society serve to facilitate rather than restrict individual choices, an on-paper not particularly liberal regime may be an open society in practice. But in the real world, the open society faces strong headwinds against it. The ameliorative tradition of liberalism is critical to mitigate those forces that push societies to become ever more rigid, suffocating, and stagnant.

But mitigation alone is not enough. In order to achieve a society where, as Rebecca Tiffany put it, “Every trans eighteen-year-old who is stuck living with unsupportive family [is] able to afford an apartment in a vibrant urban space with transit on a minimum wage job,” you need a significant amount of institutional and social infrastructure in place. You need schools that actually empower students to navigate a dynamic society. You need enough housing and transportation infrastructure of all kinds to be able to leave an untenable living situation without risking homelessness. You need economic and welfare policies that enable both general prosperity and set a high floor on personal wealth. Freedom from want is not a noble ideal just because it mitigates against the suffering inherent in poverty—it is also a key pillar in making a society truly open, as personal wealth is nearly synonymous with choice in a modern, commercial society.

The contradictions of an open society

The quest for a truly open society is neverending, and not just because it is a lofty goal. It also contains intrinsic tensions within it. Actually existing freedom to associate or disassociate can quickly become a tool to make people fear expressing themselves, if doing so carries the risk of ostracism. Actually existing freedom to express themselves, on the other hand, can quickly turn into freedom to humiliate and belittle, tactics which can intimidate people into self-restricting their own choices.

So much of the cancel culture debates circled these basic tensions without facing them squarely. There is no version of the open society where ending a friendship with someone over their beliefs or statements is out of bounds, and yet it is undeniable that if enough people are willing to end friendships over some specific belief, people will become afraid to express that belief.

We do need to regulate the potentially domineering aspects of freedom of association. That is why we have anti-discrimination laws in this country; this isn’t a matter of abstract principle, it’s a matter of targeting the specific mechanisms by which black Americans had their freedom restricted. On the other hand, private organizations must nevertheless be allowed relatively wide latitude to determine their membership and who they associate with, even if their criteria are not exactly liberal in and of themselves. As Jacob Levy put it, you couldn’t enforce freedom of religion by forcing churches to allow all comers regardless of religious beliefs;

A church that is unable to insist on adherence to its own religious tenets as a condition of membership is unable to be a church.[2]

Here is where we cannot avoid speaking in ameliorative terms to some extent. These tensions are ineradicable and the best we can do is to aim to produce societies where it is easy to find other people who share your beliefs and values to minimize the risk of ending up completely socially isolated for holding them. Of course, some beliefs and values are at odds with the open society itself; an open society where fascists successfully persuade enough people to become fascists isn’t going to remain open for long.

And indeed, that is precisely what we are seeing in Trump’s second term: an attempt to make American society less mobile, less tolerant, less educated, less free. Really existing open societies must be able to survive the existence of small minded people who yearn for simplicity and predictability over dynamism and responsibility.

Do these contradictions and these dangers imply the open society is simply incoherent as an ideal?

They do not.

A moving and relative target

Even in 2025, the United States is without question a more tolerant and open society than the United States in 1950, 1920, or 1860. Absolute openness is certainly an incoherent ideal, for precisely the reasons discussed in the previous section—absolute freedom of association implies absolute freedom of social sanctioning regardless of its consequences for freedom, absolute openness to even fascists implies openness to the implementation of fascism and therefore the destruction of the open society.

But relative openness is perfectly coherent. If a larger share of society relative to other times and places is able to say what they wish to say without fear, and to freely associate with others without finding themselves socially isolated, that is a tremendous accomplishment, worthy of celebration. We should always seek to push those boundaries further, but not at the expense of other important goals, such as the maintenance of the open society itself. Stigmatizing fascist beliefs is not at odds with the ideal of the open society because a commitment to that ideal is not a suicide pact.

The internal tensions and dynamic nature of the open society make it not only a relative target, but a moving one. For some societies, simply creating strong property rights will introduce a great deal of dynamism and undermine entrenched elites. But over time, the winners of this new arrangement will seek to entrench themselves. A good liberal cannot stand back and let this happen; they need to be anti-oligarchical even when the oligarchy emerges in a framework of liberal rights. Technological change can also undermine old arrangements that were set up for good, liberal reasons. In short, the factors that enabled an open society in the past may end up being used against it as the factions of society adapt to the status quo arrangement. Liberal institutions must make constant adjustments to safeguard the fundamental openness of society, and liberal politics must be ready to adapt as emerging threats to that openness are identified.

Standing for an open society

If liberals are to stand for something, as Demsas insists, then it must be the open society. In spite of the words I spent arguing the particulars above, I do not think this is actually very complicated. The ordinary liberal in America today largely understands this already.

But it bears repeating: we are not just against the reactionaries, the xenophobes, the racists and sexists. We are not just against kings and dictators. We are for a world where people can go where they wish to go, be who they wish to be, do what they wish to do. A world where a trans person with an unsupportive family, but also a religious convert who feels uncomfortable living in their secular household, can move out and find community without risking homelessness. A world where people are not only allowed but encouraged and enabled to find and pursue their particular path to flourishing.

That is what liberals stand for.

[1] Jacob T. Levy, The Multiculturalism of Fear (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2004), 209.

[2] Jacob T. Levy, Rationalism, Pluralism, and Freedom (Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2015), 53.

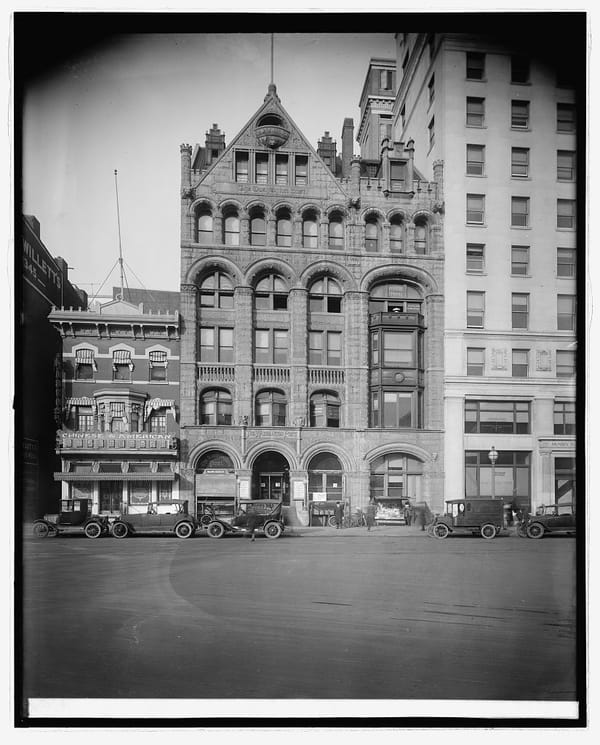

Featured image is Immigration Rally, by Karen