Machiavelli and the Liberal Republic

It is hard to not think of ancient Rome when walking the streets of Washington, DC. Rome’s legacy is carved in marble and granite and casts long shadows on the banks of the Potomac.

The common quip that the United States is a ‘republic not a democracy’ suggests in part the intellectual dimension of this legacy. In addition to the liberalism derived from Locke, Hobbes, and Montesquieu, the Founding Fathers drew considerable inspiration from republicanism, a political tradition stretching back through Italian city-states to the “utmost height of human greatness” (Federalist No. 34), the Roman Republic.

At this moment of discontent with liberalism and growing flirtation with populism and post-liberalism, it is worth looking back at republicanism in the hope its teachings can help reinvigorate liberalism.

Republicanism is a heavily furcated tradition. Ancient republicans, their early modern students, and the neo-republicans differ in their emphases and their phrasing, each in dialogue with the politics of their times. Quite consistent, though, is a belief in the importance of non-domination, the public good, and continuity. The republican tends to view liberty, the ability to “live under … [no master] at all” (Cicero’s The Republic II.XXIII) and “[enjoy] what one has,” (Discourses on Livy I.16) as achieved through the state, not despite it. A good state is therefore one that facilitates liberty and resists the fall into tyranny. In looking to republicanism to aid liberalism, a productive place to begin is with the thinker John Adams referred to as the “first who revived the ancient politics,” Niccolò Machiavelli, and his dissection of republics in the Discourses on Livy.

It is perhaps anachronous to claim any pre-Enlightenment figure was a liberal. This is especially true for Machiavelli, that “teacher of evil” (Strauss’ Thoughts on Machiavelli). Machiavelli’s praise of Numa for establishing Roman religion and his writings on principalities may preempt his even being considered a ‘proto-liberal’, whatever that nebulous term means. To see how Machiavelli’s pre-liberal republicanism can aid liberalism, it is important to first understand how Machiavelli describes the nature of the republic.

The republic, to Machiavelli, is the only sustainable alternative to the principality and personal rule. It is a state incorporating diverse interests, ideally with a poor citizenry but abundant public wealth, and governed through a thick religion.

Liberals tend to build outward from a strong concept of individual rights and moral equality. Machiavelli works on a different scale, constructing republics from groups and class interests. Machiavelli divides society between the nobles, “haves” with a “great desire to dominate”, and the populace, “have-nots” who have “merely the desire not to be dominated” (DoL I.5). Conflict between these classes is the cause of legislation that preserves liberty but is also always capable of destroying liberty.

The best state is therefore not a principality, an aristocracy, or a democracy but “one that shared in them all, … stronger and more stable” (DoL I.2). Machiavelli does not mean here that a republic needs a king but rather the “royal power” (DoL I.2), explaining that Rome’s consuls possessed this power after its kings were driven out. Fear of royal power is necessary to temper the conflict between nobility and plebeians, enabling the strange admixture of aristocracy and democracy.

Heritable political power clashes dramatically with most liberals’ base principles, resulting in a general distrust of monarchical politics. This power by pedigree is not required for the prince of a Machiavellian republic. Indeed, when “the populace is the prince,” (DoL I.58) and the people elect their own magistrates, republics are often more successful. But we must still tease out what aspects of aristocracy Machiavelli believes are so beneficial to the republic.

The Waltons and Kochs are no Medicis, obviously, but private property is still the most volatile issue in politics—fascism often arrives when socialist movements cause the property-owners to fear expropriation. Machiavelli recognizes that “so great is the ambition of the great that unless in a city they are kept down by various ways and means, that city will soon be brought to ruin” (DoL I.37). Indeed, this is why “ways and means whereby the ambitions of the populace may find an outlet” (DoL I.4) are so necessary.

It is necessary to curb the appetites of the populace to avoid the powerful creating tyrannies to protect their hoarded wealth. Just like nobles, the products of “the evil of hereditary succession,” the wealthy must be averted from “[laying] … the world in blood and ashes” (Paine’s Common Sense). Conflict over wealth is more injurious to a republic than conflict over honors for “great was the obstinacy with which [the nobles] defended [property]” (DoL I.37).

In addition to an institutional balance between the nobles and the plebeians, moderated by the royal power, Machiavelli believes that a shared religion is a necessary element of a functioning republic.

Machiavelli’s proclamations that there is “no surer indication of the decline of a country than to see divine worship neglected” (DoL I.12) and that “the observance of divine worship is the cause of greatness in republics” (DoL I.11) appear at odds with value neutrality and religious freedom, both central to liberalism. While Locke still regarded atheism as harmful to a state, he wrote in favor of religious toleration, and religious freedom has been a cornerstone of liberalism throughout its history. It is worth asking why and how religion was necessary for Machiavelli’s republic.

Religion is “[helpful] in the control of armies, in encouraging the plebeians, in producing good men, and in shaming the bad” (DoL I.11). It is a means, not an end. Machiavelli makes much of religion’s role in reinforcing oaths and of “the magnitude of that confidence which religion gives when properly used” (DoL I.15). By wise use of religion, the republic can bind its citizens even more closely to necessary ends. While religion is well-suited to this purpose by dint of supernatural threats and promises, it is not immediately evident that this external source of legitimacy and power for the state cannot lie elsewhere.

Garry Wills, in his incredible exegesis of the Declaration of Independence Inventing America, describes the Declaration as lending itself to a national myth of an “extraordinary birth, outside the processes of time” (Inventing America Prologue). In this reading, the Declaration’s legendary status in the national canon has enabled the American project, with Lincoln drawing upon belief in America’s special origin and destiny in order to shepherd the nation through trial by fire. Similarly, cries of “Vive la République” still pepper French politics, referencing a political history spanning centuries and implying continuity, a shared purpose, a common bond. Civic ‘religion’, lacking any supernatural dimension, can still serve to cohere the citizenry and to connect individual action to higher values and to the future.

The degree to which Machiavelli’s republic can be harmonized with liberal values and traditions may be interesting but mere parallels do not add to practical knowledge. It is where the republic differs from the liberal state that we can glean the most insight. The most productive point of contrast presently is Machiavelli’s understanding of virtù.

A focus on public institutions seems fairly endemic to liberalism, with Acemoglu and Robinson’s Why Nations Fail a recent archetypal example. In addition to institutions, Machiavelli draws his students’ attention to the people as a body. The people can be virtuous or corrupt, accustomed to liberty or tyranny. In a republic, new laws can be made “ineffectual because the institutions, which remain constant, corrupt them” (DoL I.18) but those new laws might be required not because the old laws have lost their virtue and wisdom, but because the people have. “[A] republic cannot survive nor be governed at all well unless in it there are citizens of good repute” (DoL III.28).

A lack of public morality and sense of the common good is one of the most common critiques of liberalism. Per its critics, the liberal state creates atomized, self-interested citizens: citizens of the market, not the polis. Whether these charges come from the religious or the sacrilegious, they point through the individual to stinking rot within civic institutions, the unraveling of the social fabric.

“Those who talk about the peoples of our day being given up to robbery and similar vices, will find that they are all due to the fact that those who ruled them behaved in like manner” (III.29). Contra vulgar understandings of public vice, Machiavelli understands that the moral orientation of the public is largely a product of the orientation of the state towards the public. If the public’s virtue is a result of “the type of education by which their inhabitants have derived their way of life” (III.43), then we must strive to establish such modes and orders that individuals have the freedom to live productive lives in communion with their fellows.

If we want to create such virtuous states, we needn’t abandon the freedoms afforded us by liberalism, as the post-liberals counsel, but rather pay attention to the state’s role as an actor in and upon society. The state must now be used not as a cudgel but as the seal upon a new compact amongst and with all its people.

The New Deal provides a vital albeit imperfect model for such a state. Government power was successfully used to protect and shore up civic groups and institutions, provide for the indigent through public services and opportunities, and bring a breaking nation together. By creating “public spaces in which we are not merely welcome, but which belong to us and give us pride” (Why The New Deal Matters) and by investing in human dignity, the New Deal was able to create the social infrastructure necessary for the rare “people’s revolution [aimed] at peace and not at violence” (Wallace’s The Century of the Common Man).

Recent interventions into the economy, following the twin crises of the 2008 financial collapse and the COVID-19 pandemic, have merely restored and not refounded our flawed institutions. Public funds successfully restarted the economy’s stalled engine but no new order was created. There was no real equivalent to the new public parks, libraries, and citizenship created by the New Deal. The American Families Plan, the most recent attempt to create new pro-family institutions, died in the Senate, beset by partisan and bureaucratic obstruction. Wealth and power still accrue to those acting in the private not the public interest.

If liberalism is to benefit from that “infinite number [of highly virtuous rulers] each succeeding the other” (DoL I.20) that results from a virtuous people voting, then the horizons of what is possible must be expanded. We must be open to creating new public fora, new ways of rewarding those who act in the public interest, and new ways of curbing the returns to the myopically self-interested. The preservation of liberalism’s political and social freedoms cannot and will not be found in the glorification of everyone working in their own self-interest, but rather in the founding and refounding of social democracies consisting of friendly peers. More attention must be paid to how our institutions and rituals cultivate civic virtue. A free citizenry should encounter and understand the state not as a threat to liberty but as an enabler of it.

“A well-ordered republic, therefore, should … make it open to anyone to gain favour by his services to the public, but should prevent him from gaining it by his services to private individuals” (DoL III.28).

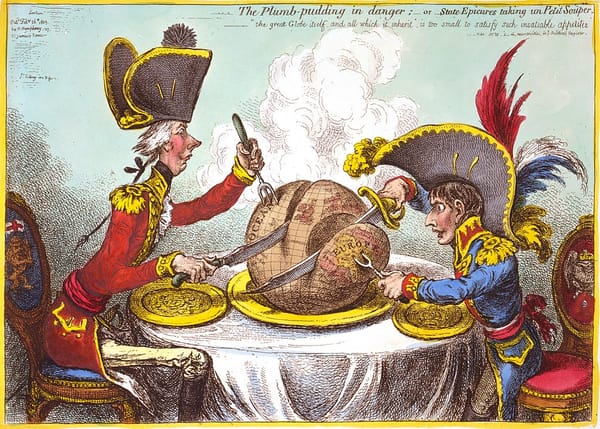

Featured Image is Cesare Borgia Seated with Machiavelli, by Federico Faruffini