Misunderstanding Early Modern Japan

Jacobin's analysis of "Shogun" betrays an ignorance of the basic history.

Shogun was produced within a series of doublings: Asia and Europe; Japan and the outside world; the seventeenth century, the mid-twentieth century, and the present; history and fictionalized versions of it; the author’s life and his writing; his life and our view of him; a book and its adaptations; and one human being and another. It is on such half-successful encounters that the 2024 television series, based on the 1975 book by James Clavell, relies for its impact; and it is within them that the first season has been viewed and critiqued.

This story was based on the life of William Adams (1564-1620), who in 1600 became the first Englishman to visit Japan, where he became an advisor to the powerful general and eventual shōgun Tokugawa Ieasu, fictionalized as Lord Yoshii Toranaga. Early-modern maritime Asia is not well known in the English speaking world. It would be easy to describe encounters between Europe and Asia in 1600 through the lens of developments after about 1800. In this view, early-modern military and sociopolitical changes known as the “military revolution,” including gunpowder weapons, better organization, and changes in military finance, were responsible for the “rise of the west” hundreds of years later. This is the approach taken by Joe Mayall in his recent response to one half of Shogun’s first season. Mayall believes that Shogun presents “imperialism’s inaugural moments.” He believes that Portuguese traders and missionaries intended to colonize Japan, and that Portugal imposed a “capitalist or mercantile economic system” on Japan, “creating a dependence from which the indigenous population [could not] escape.”

But it didn’t take “deceitful economic plunder” to plug early-modern Japan into capitalism. This period was an “age of commerce” across all of maritime East and Southeast Asia, from Japan to what is now Indonesia. When the Portuguese arrived by accident in 1543, Japan was already deeply embedded within Asian and Asian/European networks of trade. As they expanded, these networks linked Asia, Europe, and the New World in the world’s first truly global systems. The “black ship” in Shogun is a fictionalized version of just one tiny part of these networks, Japanese merchant ships bound for Southeast Asia.

This early-modern Pacific trade was permeated with profound injustice: for instance, the silver that ran both the Spanish and the Chinese economies was extracted by forced Indian labor in the vast mine complex at Potosí. The process required mercury and the death toll was atrocious. But the oppression ran much more from powers like the Spanish, Portuguese, Japanese, or Chinese toward their own subjects than from west to east. Instead of a bipolar world, newer scholarship has emphasized the multipolarity of this region, as well as common standards of human behavior underlying cultural differences. In the 1650s, when a Dutch ship seized a Chinese ship, its owners sued the Dutch crew in a Japanese court and won.

Mayall may believe the encounter between Japan and Europe was one between a traditional and a modern society, because this is how Clavell originally presented it in the novel. But Japan in this period, like England, the Netherlands, Spain, and Portugal, was not static—they were all early modern. The societies depicted in Shogun were all changing, for similar reasons that were common throughout Eurasia. When Adams’s fictionalized counterpart John Blackthorne arrived in Japan, it was the meeting of two tines of an immense crescent.

Crucially, as of 1600 Europe and Asia were at rough technological parity. Recent scholarship has emphasized that Europeans had no general military superiority in Asia in the early-modern period. In contrast to the idea of China as isolated and militarily static, we now know that it underwent many periods of military technological change as well as periods of stasis, including the development and wide use of gunpowder and gunpowder-adapted fortifications. After gunpowder was developed in China, it diffused across Eurasia; Japan obtained more modern firearms when the first Portuguese traders arrived with Chinese seafarers more than 50 years before Shogun is set. The Japanese rapidly developed firearms of their own, as well as the tactics to use them. Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582) may have developed the musket volley independently several years before the well-known military reforms of Maurice of Nassau in the Netherlands. Clavell probably didn't know this, and just as probably it wasn’t his fault. The 2024 show changed the book’s description of Blackthorne as a source of new technology and new tactics, but not enough. (There should be more guns.)

Mayall relies for his understanding of early modern Japanese and European history on part of the first season of Shogun, but this history is almost all presented from Blackthorne’s point of view. He is the one who tells the audience, through telling Toranaga, that the Portuguese intend to colonize Japan, which in real life they did not. Blackthorne also believes he should ally with Toranaga against them, and that he is powerful enough to make this worthwhile. But his perspective is limited and biased; as the episodes progress, we see that Toranaga has been using both Blackthorne and the Portuguese for his own ends, which are greater than either comprehends. The scene in S1E2 where Blackthorne described Portuguese aims as he understood them is the basis for the visuals in the title sequence in which his ship draws a line through the sand in a rock garden, both ship’s course and map of the world. This scene made a great impression on Mayall: “Scribbling a world map in the sand, Blackthorne explains to his Japanese audience that, in Portugal’s view, Japan belongs to them. The Japanese are rightfully aghast. ‘Did he really say belongs?’ Lord Toranaga asks in disbelief. Blackthorne nods as dramatic music swells.” By the season’s conclusion, the viewers understand that Toranaga had been dealing with the Portuguese all along; he had probably been feigning astonishment.

Shogun and responses to it are vehicles whereby we critique ourselves through examining the image of another. Mayall views the European influence in Japan circa 1600 as “destabilizing” it in order to take it over, as an analogy to US involvement in South America during the Cold War. He does not conceptualize the early-modern Japanese as agents, as themselves capable of high politics.

The Portuguese, Spanish, and Dutch didn’t “destabilize” a previously “stable” society: Japan in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries was tumultuous already. Toranaga’s rise to power is not the end of a politically stable order in Japan, but its beginning. Blackthorne introduces no new technology, and he doesn't lock the Japanese into “capitalism.” He becomes one element of a social context that is already technologically advanced, already commercial, and already violent. It is only very late that we realize that Blackthorne is less important, far less important, than he thought he was. The book is more blatant: at the conclusion, the reader sees Blackthorne through Toranaga's thoughts. Only then do we realize that Toranaga is Richelieu in a different shade of silk, and he had played Blackthorne all along. (Meanwhile, Toranaga’s wily lieutenant Yabushige—cruel and thoughtful, swaggering, probably into men—would have made an excellent seventeenth-century European general. Which is hinted at in S1E10, when he knows he must die and asks Blackthorne to take him to England.)

Portuguese aims in maritime Eurasia were stranger than anything mentioned in the show: destroy Muslim holy sites, advance and take Jerusalem from the east, and bring about the apocalypse; failing that, undercut Venice on the spice trade. If the writers included actual early-modern Portuguese grand strategy, the audience would think they made it up. But a similar devouring ambition drove Toranaga’s predecessor. References are made throughout the show to a previous war in Korea, in which both the nobles and the ordinary villagers of Ajiro took part. This was the Imjin War (1592-1598), led by the previous overlord of Japan, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, fictionalized in S1E2 as Nakamura. Hideyoshi intended to conquer not only the Korean peninsula, but China as well—eventually the entire known world, including Portugal. To assert that East and Southeast Asia were without imperialism or commerce before the Europeans arrived is to assert they were without human activity: the garden of Eden is a place without sin, and also the place of animals.

A thousand pages of historical notes went into Shogun. Movement coordinators taught the Japanese actors how to walk and stand. The Japanese dialogue is written in seventeenth-century Japanese. The Japanese clothing—although not the makeup—is accurate. The same is not true for the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, and English characters. Blackthorne not only walks, stands, and thinks like a modern Westerner would, the guns are off by at least a hundred years and the Europeans’ clothing is not very good. The effect is not only that an Englishman has run by accident into Japan in 1600, it’s that the audience has. In real life, both the society Blackthorne grew up in and the one he worked for are alien to us.

Who sees? Who gets to be seen? As what? Mayall believes that the message of the first half of Shogun was “dehumanization,” “the heart of colonialism.” James Clavell was born, brought up, and lived within overlapping colonialist contexts—that of English servants of the British Empire abroad, but also Imperial Japan: he was captured by the Japanese in 1942 and imprisoned for several years. His work was shaped by these contexts, but reached beyond them; for instance, he wrote and directed To Sir, With Love (1967), in which a black West Indian immigrant to the UK reforms the students in a rough high school through his personal example.

Instead of being advertisements against capitalism, Clavell's books and movies are all, in the broad sense, liberal. Clavell was anti-communist: a free enterprise proponent who hated the Labour party and corresponded with William Buckley. He was also anti-racist, and depicted his commitment to pluralism and multiculturalism in his books. His highest virtues were adaptability, individuality, pragmatism, and strength of will. At times this leads Clavell away from the seventeenth century: Blackthorne’s commitment to personal freedom is not accurate. At times it leads Clavell toward the seventeenth century. At times it led him to something sublime, an attempt to step outside both “Asian” and “Western” points of view into the contemplation of a greater, indifferent universe.

One of the themes of Shogun which I have not seen very many people exploring is not colonialism, but gender. The show is very clear about what relationships between men and women are like in a violent society which prizes martial valor. It is through masculine acts that Blackthorne and men like Yabushige understand one another, even before they know each other’s languages, and it is as a man—as a fighter—that Blackthorne eventually attains a place in Japanese society. The similar standards of human behavior underlying European and Asian cultural differences not only include the fairness that enabled a Chinese ship’s crew to sue a Dutch crew, but also the deployment of gendered violence. The show depicts sexists while attempting to avoid sexism. Blackthorne and his Japanese translator, the Christian noblewoman Mariko, feel deeply for each other but never actually get into a relationship; he and Mariko’s brutish husband Buntaro begin as rivals, but this is also misdirection, since they bond after she dies in S1E9. In traveling to Japan, Blackthorne has gone from one militarized patriarchy to another.

Forty-four years after the real William Adams arrived in Japan, Matsuo Kinsaku (1644-1694) was born. Under the name Bashō, he became Japan’s greatest master of haiku. One of his poems reads:

the whitebait

opens black eyes

in the Net of the Law

The last line compares the fine net in which whitebait are caught to the Buddhist doctrine of interdependent origination, which refers to the networks of causality which produce all phenomena. Because they are all caused by one another, phenomena have no essential nature in the Aristotelian sense and are thus “empty;” to understand this is to be liberated, like infant fish—whitebait are immature fry—opening their eyes when they are about to die. These causal networks include the social, economic, and political organizations within which men fight. During the early modern period, these systems changed substantially in Europe and Asia. The Japanese and European men in Shogun are caught within them. In Shogun’s first sex scene, Yabushige watches a prostitute have sex with his retainer and the camera cuts immediately from the young man’s naked body to Blackthorne’s: within these terrible meshes, all men are equal.

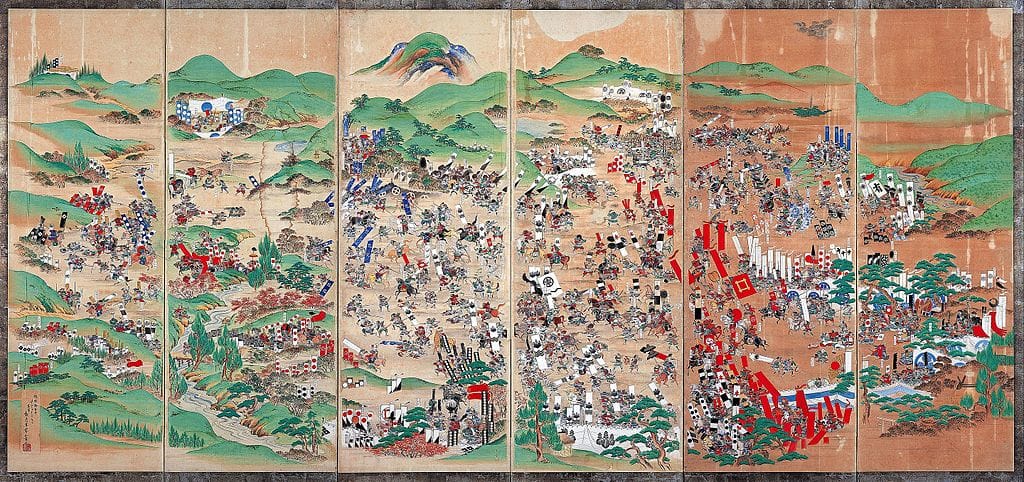

Featured image is Sekigahara Kassen Byōbu