Neon Liberalism #22: We Can Fix Housing

Samantha and guest David Vatz, founder of Pro-Housing Pittsburgh, discuss the meaning of the housing crisis, the death of the "asset economy," and what we liberals can do to fix housing despite Trump.

Neon Liberalism can be heard on Spotify, on Apple, on YouTube, on Amazon, and elsewhere via its RSS feed.

References

Pro-Housing Pittsburgh's website: https://www.prohousingpgh.org/

The Asset Economy: https://www.amazon.com/Asset-Economy-Lisa-Adkins/dp/1509543465

The Crisis of Democratic Governance: https://www.liberalcurrents.com/the-crisis-of-democratic-governance/

Full Transcript

Samantha Hancox-Li [00:00:09]

Hello and welcome back to Neon Liberalism, a weekly podcast where we talk about the world today and try to put things that are happening into a larger historical and theoretical context. This week, I am very excited to have on David Vatz, the founder of Pro Housing Pittsburgh. David, thanks so much for coming on the podcast.

David Vatz [00:00:45]

Thanks a lot for having me. I appreciate it.

Samantha Hancox-Li [00:00:48]

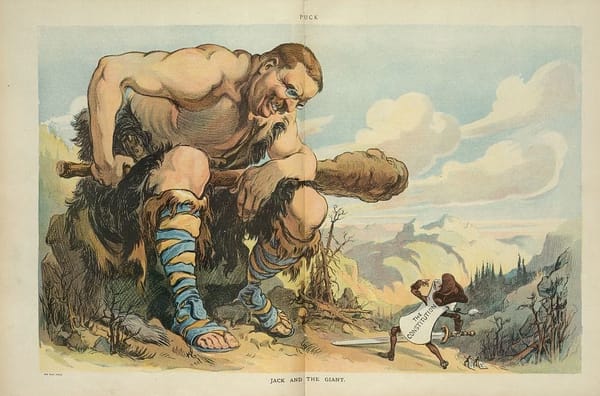

I asked you on because last week I had on Jamelle Bouie and we talked about this idea of constitutional settlements, and the alignment of large political and economic forces that stabilize the constitutional order. One of the things he said was this sense for a lot of people in America that the economy isn't working anymore, that something has really broken in the American economy.

Personally, I think one of the most fundamental things that has broken in the American economy today is housing. I wanted to talk about the context of that. Why is housing so important? How did housing break, and what can we do to fix it?

Why don't you give me the pitch? What's Pro Housing Pittsburgh about?

David Vatz [01:46]

Pro Housing Pittsburgh is a group based out of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania that I founded almost four years ago, with the goal of making Pittsburgh housing abundant and affordable to everybody. Broadly speaking, we are a YIMBY group. We advocate for building more housing.

We have seen a ton of success because many people do see housing as one of the biggest challenges. You have people, especially younger millennials and Gen Z folks, who see the American dream as being unattainable for them now. You see it in all contexts, and among people from all walks of life, that they see housing as a major challenge. It's not affordable to them, or they don't see the ability to ever own a house, or be able to be in the type of home that they envision they would be someday.

Samantha Hancox-Li [02:43]

That's great, and it's worth emphasizing that housing is not just one little thing that you purchase in your life, but it's central to everything else you're going to do. Where you live is going to determine what kind of jobs you can get. It's going to determine what kind of education your children can get. It's going to determine where you personally can go to school, depending on the situation.

It's going to influence the world you live in, what you see out your front door every day, and as we're going to probably come back to, quite often, it's going to influence your financial future, depending on what you own and whether you own and where you own. So many different things come together in housing. It's not just a little silo. It's not just one among many economic problems, but it connects all of them together.

David Vatz [03:45]

Housing is so important to people because it's tied into a lot of emotion. It is where you live. It is what you build your life around. It is your social circle. It is your educational possibilities. It's your job possibilities – it is everything.

Right now, we're in the midst of a mayoral primary in Pittsburgh, and voters are saying in some of the polls that have been released that housing is the number one priority by a wide margin of all the different topics. It's higher than public safety, it's higher than other things like that. It's very clear that people feel this. It's not just a financial consideration. It's also an emotional thing. It's also their sense of being in the community. So it's super important.

Samantha Hancox-Li [04:41]

It's also worth talking about housing because I'm a liberal, a Democrat on the federal level. Democrats are not in power. We don't control the Supreme Court, either house of Congress, or the presidency. But housing policy is mostly made at the local and the state level. So even if over the next four or however many years, we can't get our hands on the national levers of economic change, there's a lot we can do still at the local, city, and state level, to try and make housing work for everybody.

David Vatz [05:20]

One of the magical things about housing policy is that almost all housing policy is hyper local. Here in Pittsburgh, the vast majority of housing policy is set locally.

There's a federal role for things like LIHTC and some affordable housing funds, same thing with the state, but really, the ability to decide what can be built and where can it be built is almost entirely up to our local legislators. In Pittsburgh and Allegheny County, we have 130 different municipalities that set their own land use rules, Pittsburgh being the largest of those municipalities.

You have the ability to make a lot of change locally just by understanding what the land use policies look like in your area, and starting to learn what could we be doing to fix those things, to make the rules better. It's really what we've focused on as a group – figuring out how we can impact some of these local rules to make housing more abundant in Pittsburgh.

Samantha Hancox-Li [06:35]

That's definitely something I want to come back to, this question of what can we do. But before we get to that, I want to talk about history and the sense that housing wasn't always a crisis in America. This isn't something that was with us from the first days of the Republic. The housing crisis is something new. It's something that broke in our lifetimes.

If I had to ask you, how did we break housing in this country? What did we do that led to housing being such an enormous chunk of our incomes, or for many people, just out of reach?

David Vatz [07:19]

It's a really good question. You do have to go back a little over 100 years to really start to figure out why housing is so broken.

Many people take for granted that we have zoning rules and restrictions on what can be built, where and how it can be built. The first zoning codes in America were put in place in some of our larger cities, and were put in place primarily to segregate certain groups, to keep certain groups out. Some of these early zoning codes in places like New York and Los Angeles - that's what their purpose was. Their purpose was to keep undesirable groups, minority groups, primarily racial minorities, ethnic minorities, out of the white areas of the cities.

The Supreme Court struck those early zoning codes down and decided this is not legal. But then there was a landmark case, Euclid versus Ambler, where they found that what we now know as zoning, Euclidean zoning, which says we can segregate by use and by type, is legal.

So what you see in a lot of cities, including Pittsburgh, is certain areas that are single family zoning only. What does that mean, and how is that a form of segregation? Single family homes are the most expensive types of homes. You hear people talk about luxury housing and luxury apartments. The real luxury housing is detached, single family homes. They're the most expensive, they're on the most land. They're always going to be the most expensive typology in a given area.

This form of zoning called Euclidean zoning, where you could say, "In this area, you can only build single family homes," was a way of creating that segregation, but doing it in a way that the Supreme Court found to be legal. That's what we have today in basically every city in the country. Cities have been separated out into small areas where you can only build multi-family housing in a very small percentage of them, and that has created scarcity. When you only allow single family homes to be built everywhere, you limit the amount of homes that can be built, creating scarcity and prices that go up.

Right now, in Pittsburgh, you can only build multi-family housing in 24% of the city. We're severely limiting the ability to build less expensive housing.

Samantha Hancox-Li [10:14]

That's a really interesting point. I want to go back to what you're talking about, the origins of zoning as a way of doing racial discrimination without saying you're doing racial discrimination. Not all zoning is necessarily like that, but a lot of it is because what we're talking about here is producing a social outcome. In this case, it's racial segregation, but you do that through technical stuff, by controlling land use, by controlling what kind of buildings can be built, by controlling the process that allows you to build different kinds of buildings.

One example I like is the way fire codes have been developed. Everybody says fire codes are obviously about safety, and in many ways they are. But there's also evidence that the people who originated our fire codes explicitly said they were going to regulate fire safety for larger buildings very intensively, and not really at all for single family homes. Inherently, that makes multifamily more expensive, resulting in less multifamily. The people who made these codes wanted that – they thought apartments were for poor people, and therefore they would regulate them out of existence, leaving only nice single family neighborhoods.

David Vatz [11:43]

You're absolutely right about that. It's funny when you start looking into why codes say this or that. The answer is, oftentimes, one person said this should be the code, and that's what we went with, and we stuck with it.

There's a lot of discussion happening right now about single stair reform. For folks who are listening that don't know, most apartment buildings require two stairwells for egress in case of a fire. Throughout the world, there are tons of apartment buildings with only a single stairwell, and they're perfectly safe. There's not really any evidence that single stair buildings, particularly with modern fire codes with sprinklers and things like that, are less safe. However, at some point back in history, someone put in "you must have two stairwells," and that became the gospel.

A single family home doesn't require two stairwells. Therefore, it's simpler and less expensive to build that than it is to build large apartment buildings, which are inherently just going to be a less expensive option, so we're forcing the prices up.

I don't think anybody would argue against basic safety regulations. Obviously we need those sorts of things, but it's when you have these regulations that are potentially produced with an ulterior motive. I don't think people think about it this way, and it's not to say that there's not good that can come out of these things, but a lot of times these are created as a back door to segregate, or to make it less appealing to build apartments, because apartments are thought of as where the poor people live. "We don't want that in our neighborhood, therefore, let's make it really hard to build it."

Samantha Hancox-Li [13:46]

That's exactly right. I want to talk a little bit more about history. We get these first zoning codes starting in the 1920s but we don't immediately proceed to what we have today - totally unaffordable housing.

One picture of what was happening in American cities in the middle of the century was that they were dominated by what was called the growth machine. Growth machine politics says we are going to build more housing in our cities, so that more people can come to live here, and they are going to get jobs, creating more tax revenue that we can use to spend more on social services, leading to more development. It's a machine.

The machine was corrupt in many ways. It had other kinds of problems with it, but it definitely grew American cities, and that economic settlement breaks down at some point. People stop being satisfied with it.

Let me tell you a story, and you tell me whether you think this is plausible. There's a book I like called "The Asset Economy," by Melinda Cooper, Lisa Adkins and Matthias Koenig. Their position is that after stagflation, after the Volcker shock, after the crisis that destroys that mid-century economic consensus, a new economic consensus emerges - what they call the asset economy.

In the asset economy:

- Economic growth is going to be lower than it used to be

- Wage growth is going to be lower than it used to be

- Inflation will be managed - always very low, carefully controlled

- To compensate people for lower wage growth, we pursue asset inflation

What that means, effectively, is that we are going to really tightly restrict the supply of housing. We had zoning already, but we're going to crank zoning way up. We are going to make it much harder than it used to be to build housing through a wide variety of methods, and then other kinds of macroeconomic changes are going to pump a lot of money into the housing market.

If you're a homeowner, on one hand, your wages aren't growing as fast, but your home equity is doing great. Do you think that's an accurate picture of the 90s?

David Vatz [16:46]

For sure. We've seen it all across the country. We've seen home values go up and up where wages stagnate, but people feel okay about it, because they say, "My house is worth $200,000 more than when I bought it."

I've thought about that many times, though - if your home value goes up, what do you really have? Has that really benefited you? Because you need somewhere to live. If you say, "My house has gone up by $200,000, I'm gonna now move to a better house" - you can't do that because that house went up too.

Where does that increase actually get you? To me, it's kind of like a mirage of wealth. Home equity feels good, but is it really getting you a better life? When I think of what the purpose of the liberal project is - what are liberals and progressives trying to produce? We're trying to produce better lives for more people. Does home equity really get you a better life? Probably not in my opinion.

Maybe someone might disagree with me about that, but I'm thinking no, because you can't use it effectively. I mean, you can spend your home equity by taking out a loan on it, but that's still a loan, and you still have to pay that back. So it's not the same as getting higher wages, which actually probably leads to a markedly greater quality of life.

Samantha Hancox-Li [18:18]

I think that's exactly right, because fundamentally, people who own a home like it when their home equity grows. But on a macroeconomic level, just because we've made housing scarce doesn't mean we have more stuff in the world. It's just kind of moving around who's got which slice of the pie. It's not actually making the pie any bigger.

David Vatz [18:43]

Right, and I've had this conversation with people. You see this messaging a lot from Democrats over the last few years about "we need to get more people into home ownership so that they can build generational wealth."

I've thought about that and said, having more people as homeowners is a great goal. However, this idea of generational wealth is coming from someone else, essentially. If homes themselves are an appreciating asset that lead to generational wealth, what that means necessarily is that homes are unaffordable for other people. You can't have homes appreciating in perpetuity, and then also have homes be affordable to everybody in the general population. You kind of get to pick one there.

It's good messaging, and that's the reason why you hear that from a lot of politicians. But ultimately, that relies on scarcity. You must have scarcity if you want to see home prices go up and up. If your goal is for homes to be affordable to everybody, then you need the opposite of scarcity. You need abundance. You need more homes.

Samantha Hancox-Li [20:11]

That's exactly right. You've put your finger on the key point - my home equity is your housing costs. They are just two sides of the same coin, and there's no real way around that.

You can massage it for a while. One way that you talked about already is with debt. "My home equity is going up, so I can take out a loan against the value of my home, or I can engage in more consumer credit" and various kinds of things that let me spend that money in an immediate way.

You can massage it through sprawl where, "We are gonna build more homes, but they're always gonna be a little bit further out." People feel like, "I can get on that rung. I might have to drive an hour to work every day, might have to drive an hour and a half, might have to drive two hours. But at least I've got a house. I've got the golden ticket."

But as I think we're really seeing in a lot of cities in America these days, we've just run out of room to sprawl into. We've run out of tricks to play to make the mirage work.

For me, the moment when I saw this really visibly was when I was in Jersey City. I was wandering around a nice neighborhood of Jersey City, not a broken down neighborhood, and they were 100-year-old tenement buildings, like there are all across this part of the country. Parked in front of these crumbling, 100-year-old tenement buildings were brand new Teslas and Lexuses and luxury cars, because the people who lived in these old houses weren't poor, they were very well off.

We've created this enormous divergence in our economy where the essentials of life are expensive, where housing and health care and education and security in your retirement are expensive, even as the luxuries of life are getting cheaper than they've ever been.

David Vatz [22:25]

I think about that a lot. Looking back to my childhood, some of the things that we considered to be luxuries - my parents owned a car that had a manual transmission and had no air conditioning and had no radio. We didn't have granite countertops.

Now it seems like these sorts of luxuries, things like having air conditioning in your car, having an automatic transmission - very small things, not necessarily leading to a massive increase in your quality of life - these things are cheap. These things are everywhere now. Granite countertops are a dime a dozen now. That was a serious luxury back in the 90s when I was growing up.

But we've under-built so much in terms of housing that now an apartment in one of these old tenement buildings might be over a million dollars, might be over $2 million. This is particularly stark in cities like the New York metro area, Los Angeles, San Francisco - some of the "superstar cities" where there's clearly huge demand to be in those places.

The way that people deal with that is, if they want to live in San Francisco and San Francisco is unaffordable, they move further out, and they keep moving further out, and they're commuting in for jobs. This is a serious negative for these people. Of course, it's positive they have a house, they have a place to live. That's a good thing. But all else being equal, they might choose to live 20 minutes from work, not an hour and a half from work, or they might choose to live in the city center, where there's more access to job opportunities, educational opportunities, cultural opportunities and social opportunities, and maybe be closer to family and friends.

It's a big loss for society when we're not providing those things. Unfortunately, particularly in our most expensive cities, in our most high opportunity cities, that has become unattainable for most people.

Samantha Hancox-Li [24:40]

That's exactly right. You see these images that go viral on social media where you'll have 20 people, 50 people lined up outside a house in order to try and make a bid on it. And the house is, to be a little crude here, a piece of shit. It's a falling down shack that was built 50 years ago, pretty badly, but it's not even that close to anything. But people want it desperately, because cities are where the jobs are, where education is and where social opportunities are, and where everything else you want in life is.

We have deliberately under-built for decades at this point, and it just seems like it is no longer working for the vast majority of Americans. So what should we do about it? You said you're from Pro Housing Pittsburgh. You founded Pro Housing Pittsburgh. You're a YIMBY group. What do you say we should do about this problem?

David Vatz [25:52]

I think this is particularly a problem in our most progressive areas, which is, for me as a progressive, frustrating. I look at our most progressive cities and I see that these problems are the most stark in those areas.

San Francisco and Los Angeles are great examples of the housing crisis and why it's become so bad. These are places that are some of the most progressive places in our country. They are the most progressive places in the most progressive state in America. And yet, they have passed a bunch of policies that have been held up as progressive housing policies, like:

- "We're going to prevent over-development"

- "We're going to create price controls"

- "We're going to put in inclusionary zoning policies"

I would call these the false prophets. These are things that people hold up as solutions. But when you look at the results of those "solutions," what do you see? You see the cities that have the worst housing crises in the country.

Pittsburgh has by and large been spared from a lot of this as a city that has seen slow or negative growth. Pittsburgh used to have 600,000 people in it, now it has 300,000 people. That has made it so that we have not experienced some of those big problems.

However, in the last 10 to 15 years, you've seen a resurgence in places like Pittsburgh, and you've seen it in other cities like Pittsburgh, where some industries have taken off a bit, and people are fleeing some of the larger, more expensive cities to a place where they can afford a home or a place where they can afford to have a life. But the result of that is more people coming in, more demand, and higher prices.

Samantha Hancox-Li [27:56]

I agree with you that you can put off the problem for a little while by moving further and further out or finding a new city. But the problems we're talking about are not just problems for San Francisco and New York.

It is worth dwelling on this point you were making about how the problems do seem most acute in the most progressive cities. This is something we mentioned at the beginning, but the housing crisis - no Republican put a gun to California's head and said, "You have to have a housing crisis." This is not some horrible policy that's been inflicted on California by conservatives. This is something that we have done to ourselves. This is something that we as progressives have done to our own states, to our own cities.

I have an article about this at Liberal Currents called "The Crisis of Democratic Governance." One of the things I note in it is that California is losing population. The state in America with the highest wages and great health outcomes and a great educational system is losing population because of cost of living, because of the cost of housing. People are on net leaving California for Texas. Even though wages are better in California and human rights are better in California, your right to an abortion is far more secure in California, but even still, people are leaving because housing is so expensive, because we have made it expensive.

David Vatz [29:26]

It's a crisis for democratic governance. I think you look back on the election of 2024 and a part of me says, especially with what we're seeing right now out of the Trump administration, "Boy, I wish people would have trusted Democrats. I wish people would have trusted Kamala Harris and elected her." Of course, that didn't happen.

But you look at it and say, what reason have Democrats given to trust them on these things? When you look at the places that are run by Democrats, you look at California, you look at San Francisco, you look at our superstar cities that produce a huge percentage of the GDP for our country, that are hugely important to the success of the whole country - but you look at the governance of those places and you say, why can no one afford housing there? Why are there people in the streets there? Why are there huge human rights crises there in terms of drug use and things like that?

I think when you look at those things, you can understand how a person who's not as deeply involved in politics, might say, "I'm not sure that I trust, I don't want that sort of governance across the entire country."

Luckily, it's a fixable problem, but it's something that we need to wrestle with as liberals, as progressives. How do we govern in such a way, and how do we, particularly in the places where we have power, in California, in our cities like Pittsburgh, where we have fully democratic governance, how do we create rules that show that we ought to be trusted with governance across the entire country? When Texas is outperforming California, it's hard to say you should really trust us to govern the rest of the country like we govern California.

Samantha Hancox-Li [31:31]

Yes, and to be clear, there are many good things about the way we govern California, but there are also very serious problems. To get at some of those problems, why don't you talk about some of the false prophets that you mentioned - the snake oil cures of the housing crisis?

David Vatz [31:45]

When you're doing housing advocacy, it's impossible to get away from these false prophets. They will tell you:

- "If we just prevent this development, then prices won't go up"

- "We can't bring in these new homes, because if we do, everybody's prices are going to go up"

To me, that's the number one false prophecy that people tend to espouse in housing circles. It's a failed causal relationship. People believe that new development raises prices, but the reality is that new development is driven by high demand. The developers aren't creating the demand. They are responding to the demand.

That's one of those false prophecies that people try to say - "If only we prevent this development, we can save our community, and it won't become overpriced." But the reality is that people with money and means, if they are coming to your area, they will outbid the people who have less money.

In order to prevent that, you need to build more. You need to build the housing that will soak up that demand from people who have a higher means to pay. This was backed up by a whole body of research that shows that when you build new housing, it actually creates downward pressure on the existing housing. It doesn't make the existing housing more expensive. It actually makes the existing housing less expensive. Prices rising are caused by not building enough. It's not the opposite.

Samantha Hancox-Li [33:41]

That's right. I've lived a lot of places in this country, and I've seen it happening around me. It gets back to this Lexus in front of a tenement. People with money will pay to live in the tenement. They will pay for the shitty apartment. They are paying for the shitty apartment all over the greater New York metropolitan area, all over Los Angeles, because the shitty apartment is the closest thing they can afford to where they want to live.

If they have money, they will bid lower income people out of that neighborhood. This is true whether or not you build anything - they're still going to show up and still going to want to live there. The character of a neighborhood can completely change without the physical buildings changing.

It's like musical chairs. Housing in this country is like musical chairs, and who is the kid who doesn't get a chair at the end? There's always some reason for it - they're the slowest, or they have a broken leg, or they have drug problems in their life, or they have a bad job.

David Vatz [35:12]

That's a really good analogy for the housing market. One of the things that's talked about in housing spaces a lot is this idea of filtering where, when you build new supply, people go live in that and they're vacating other units. They're generally not coming from outside of the area. The vast majority of those people are already in the area, and they're going into this new housing, and they're vacating a unit, and then another person vacates a unit.

The analogy is, it's like musical chairs, but you add a chair, and so when you do that, you're providing more opportunity for people. Interestingly, the results of this, the results of these chains of moves that people have, is that it actually opens up units for bottom quintile renters. For people who are lower income renters, it opens up a bunch of units for those people when you build high income housing.

That's not to discount that you of course need other supports. There are still always going to be people in the market that do need forms of government assistance. There's a need for LIHTC projects. There's a need for Section Eight housing vouchers and things like that.

But it still behooves us to make sure that we are building enough to make it so that those programs are not needed by even more people. The more expensive housing is, the more people are going to need those forms of government assistance. Ideally, we want to use those funds in the most wise way possible and make it so that they are helping the people with the greatest need. If you don't build housing, you just have more people that have great need at that point.

Samantha Hancox-Li [36:55]

I think that's right. You can kind of see this as a situation where, if you have an artificially restricted supply of something like housing, and you say, "Some people aren't getting enough housing. So we're going to give more money to them. We're going to have funding for low income people. We're going to have funding for first time homebuyers, or we're going to build more housing for the homeless."

But if you just keep choking off the actual supply, all you do is raise the price without actually getting more people into homes. This isn't an argument against income support for poor people, for people who need housing. Income support is great if it is combined with the ability to build new housing.

David Vatz [37:42]

If you have a bunch of programs like down payment assistance and things like that, but you don't build housing, those programs won't go as far. This is the issue - you can subsidize and subsidize and subsidize, but if everybody's still fighting over the same four chairs in our game of musical chairs, ultimately the price of those chairs just go up.

You need to add chairs, or else you're just taking taxpayer money, taking government subsidies, and they're just not going to go as far, and eventually they will get eaten up by an increase in prices. Programs like down payment assistance are great, but they are still a demand subsidy. They are going to cause the prices to rise by some amount, unless you're building enough that it causes prices to not go up.

Also, if you're building enough, you might have fewer people who need those sorts of subsidies. Building is really kind of a virtuous cycle where you make it so that the limited government funds that we do have for affordability go further and people have more choices, which is a good thing.

Samantha Hancox-Li [39:00]

That's right. You can see this connecting to the political economy I was talking about earlier, the asset economy, where what do the false profits of housing do? They restrict supply and they juice demand. That fits very neatly into the asset economy, which is built on an artificial scarcity of housing, and then various kinds of policies that pump money into the housing market while keeping supply restricted, which effectively puts more money into the pockets of people who happen to own land. So there's a reason that these kinds of policies have been popular. The reason that they're everywhere is because they are inherent to this kind of political economy.

David Vatz [39:52]

One of the things that you see a lot in housing discourse is, generally speaking, the people who are showing up to argue against building new housing tend to be long-tenured homeowners. That tends to be a large group of people, and that's not to say that their opinion shouldn't be taken into account, but it is to say that they do have a vested interest in preventing housing supply. If they prevent housing supply, it creates that scarcity.

I don't think people actively think about this when they are arguing against housing. Housing is a very emotional thing. It's not just a financial transaction. Your place where you live matters a lot to you. I think people generally like where they are, and they don't want it to change.

I don't think people are going into a public hearing saying, "We can't build this new housing, because it's going to make the growth rate of my home go from 3% to 2%." I don't really think that's what people think about. But their financial incentives are aligned there. When they're arguing against housing it will likely increase the value of their home by preventing additional supply from going in.

Samantha Hancox-Li [41:08]

I think it's worth noting that in these cases, the financial incentive and the emotional incentives kind of go hand in hand. It's an asset economy that's kind of working for them, although there are some questions about that that we've talked about, like the mirage of home wealth, but it feels like wealth to them, and it feels like safety and security, and they don't want change, and they want things to stay the way they are, because they're emotionally invested in that on a certain level.

But this has all been pretty big picture, theoretical about housing, and I kind of want to bring it back down to Earth, which is to say back down to Pittsburgh. So what have you and your group been doing in Pittsburgh to try and change this situation?

David Vatz [42:00]

Building a coalition around making these sorts of changes, particularly making changes around land use policies and zoning - I don't think zoning is something that the average person really thinks about, although over the last five or so years, I think people have started to think about it more because of what we talked about at the beginning. Particularly young people are seeing that the American dream is not a reality for them. And part of the reason for that is that housing prices are just too high.

The things that we look at in Pittsburgh and the Pittsburgh area is:

- How do we adjust the land use rules to make it easier to build housing

- How do we ensure there are fewer veto points

- How do we create more possibilities on every lot, citywide and countywide

- How do we ensure there are fewer restrictions

There's something that we've spent a lot of time on - there's been talk about an expansion of inclusionary zoning. Inclusionary zoning is a great false prophet policy.

For listeners who may not know what inclusionary zoning is, it's usually some sort of a requirement that market rate developers, usually of apartment buildings, include a certain portion of their units at below market rate. It's one of those policies that to the average person generally sounds good. The first time I heard about inclusionary zoning, I thought, "Yeah, that seems sensible, we should do that."

Unfortunately, these policies have been pretty much discredited all across the nation as not accomplishing their goals. In Pittsburgh, we've had a limited inclusionary zoning policy in place since 2019. It's produced 35 units in six years.

Samantha Hancox-Li [43:56]

I want to dwell on that - 35 units across a city of 300,000 people over six years.

David Vatz [44:04]

It's a huge indictment of the policy, that that's all it's done.

When we got wind that a citywide expansion of the inclusionary zoning policy might be something that the current mayor wants to propose, we started doing some research on this. We wanted to figure out, maybe we're wrong. We want to seek truth. We want to know what is right, what is good policy, what is bad policy.

We've seen studies across the country of inclusionary zoning policies that show that it is bad and that it depresses housing supply and that it actually increases costs. What we wanted to understand is, is Pittsburgh the same? So we started doing research around April of last year, trying to understand, did the Pittsburgh inclusionary zoning policy decrease the amount of housing that's being built?

Samantha Hancox-Li [45:06]

The pilot program, I understand, correct?

David Vatz [44:08]

Yes, there was a pilot program in place, and they're trying to expand it across the city. What we wanted to see is, did the pilot program create more housing in the neighborhoods where it was or did it depress housing construction.

What we found is housing construction in the neighborhoods where it was in place was down 30%, and when we compared it to what we consider to be peer neighborhoods, those peer neighborhoods were up 36% and 18% respectively. So it's a pretty stark difference.

Granted, it's a small sample size. It's very hard to study this stuff. This is one of the things about inclusionary zoning that makes it so tough - it is really hard to study it. Because especially in a city like Pittsburgh, we're only building about 1000 units a year, give or take, so you're not working with a huge number of projects to figure that out.

But those results line up with what we've seen elsewhere in the country, what other jurisdictions have seen. I like to joke that Pittsburgh is always like 10 years late to most trends, and inclusionary zoning was definitely a trend of the 2010s where there were a lot of cities that were implementing these policies or strengthening these policies. At this point, most of those places are backtracking. Portland is a good example - Portland had an inclusionary zoning policy. Now they've decided the only way this actually works is if we fully fund these affordable units.

Samantha Hancox-Li [46:50]

My question is, so you've done some studies on the inclusionary zoning pilot program, and they don't look great. How are you taking these studies and turning them into political action and political change in Pittsburgh?

David Vatz [46:57]

One of the things that's helped us a lot is that housing has become this really hot button issue. It's become something a lot of people are interested in. We now have hundreds of people who are involved with our group, who are organizing.

One of the main things that makes these topics challenging is that public officials see programs like inclusionary zoning, and these are programs that are popular. People look at them and tend to gravitate towards them because people are not generally thinking about the second, third, fourth order effects of this policy. "Let's make the developers pay for affordable housing. Sounds good. Let's do it."

One of the things that we've really focused on, and why we've done research on it, is how can we better educate our public officials? Our public officials are not going to be experts in every topic, nor should they be expected to be. They rely on expertise from other groups, from subject matter experts and things like that, so we want to be able to provide them with some of that knowledge that might otherwise not be available. That's one of the reasons that we focused on research as definitely a core competency for our group.

Samantha Hancox-Li [48:18]

I was at one of those meetings where I believe the City Controller came to Pro Housing Pittsburgh in order to try and understand inclusionary zoning, to understand how do you actually study these policies, in order to determine their actual effects. These are city officials who are - Pittsburgh's not New York City, Pittsburgh's not the federal government. We're a small city, small enough. Like you say, these are hard working public officials who don't necessarily have all of that background and all that training, but they want to do their best. So Pro Housing Pittsburgh was, in my understanding, able to help with that.

David Vatz [48:58]

The study that we published created a really positive impact on the discourse. We are a truth-seeking group. We want to understand what's right and what's wrong. I don't think that we look at our study and say, "This is the be-all end-all. This tells the whole story." What we say is, this is a part of the story that we must take into account.

One of the things that is worth thinking about with land use policies is that they are an exercise in trade-offs. If you implement a policy like requiring affordability, that is going to create a trade-off. That trade-off is going to be it's going to become more expensive to build housing, and therefore you will get less housing. Maybe there is a situation where that is an appropriate trade-off for you to make. I don't think that's the case in Pittsburgh. We certainly don't think that's the case in Pittsburgh. But it's more about how do you create the information that helps you make that decision.

Policy decisions like this have a deep impact on the local economy. If you reduce the amount of housing that gets built by 10 or 20% you're not just impacting housing costs. You're impacting all the people who work on those buildings, who build them. You're impacting the building trades. You're impacting the neighborhoods that they exist in, whether it's by increasing their prices or providing less amenities. When you build a new building, maybe it's got new retail spaces, maybe it brings in new businesses. You're creating deep effects on these areas.

We believe that it's appropriate to do those with a clear vision into what's going to happen when you do it. Don't put the policy in because it sounds good. Put the policy in because it's going to accomplish the goal that you want.

We're also big believers in this idea that the purpose of a system is what it does. Inclusionary zoning policies - in fact, even by the admission of the original architect of the inclusionary zoning policy in Pittsburgh - one of the things she said when she announced it in 2018 or 2019 was "we need to stop runaway development in Lawrenceville."

When you hear somebody say that out loud, you think this is a policy that's supposed to be building a bunch of affordable housing, but it's also a policy that's going to curb runaway development. What is the actual purpose of it? And from what we can see, it produced 35 units, and it stopped development. So it really mostly just curbed runaway development, and it harmed people in the process.

Samantha Hancox-Li [51:51]

I live in Lawrenceville, and this is always so frustrating to me, because you can go out on Butler Street any night, especially Friday, Saturday night - people want to live in Lawrenceville. You can look at the housing crisis and you can tell people want to live in Lawrenceville. There's a lot of stuff to do here. It's close to a wide variety of jobs in Pittsburgh. You can get a one bus line or another and be right at Pitt or CMU.

So there's reasons that lots of people want to live here, and personally, I think we should let them live here. That will be better for everybody if they can live here and they can shop at the stores here and bring in more jobs for more people, that they can get their own education and work at their own jobs without having to increase their commuting time, half an hour or an hour or however long it is - which causes all kinds of environmental harms and just personal waste, economic waste, as compared to living in a better location. I just find this so frustrating. Sometimes it gets a little too personal.

David Vatz [53:04]

You're totally right, though. The prices of living in a neighborhood like Lawrenceville tell you a story. They tell you a lot of people want to live there. When people are buying up 1920s row homes for $150,000 and then you see them on the market six months later for $700,000 or $800,000, that tells you something. That tells you there is this massive amount of unmet demand for people to live in this area.

The solution is not "don't build." If you don't build anything, that just means that the lower cost housing that currently exists there will be bought up and will be converted into high cost housing. The solution is build the new high cost housing to soak up that demand and ensure that people don't get displaced in the process.

There's this idea that if you prevent the new apartment from going in, that you're going to reduce the amount of displacement. That is not what the research on this shows, and that's not what intuition would tell you. If you don't build the large apartment building, all the people who are going to live in that large apartment building who still probably want to live in the area - a subset of those people will just outbid lower income people for housing that already exists. That's what happens. That's why you're seeing people being displaced.

You're not just seeing this in Pittsburgh - this is happening across the entire country. So the solutions that we are trying to work on with our public officials, in terms of setting better policy, is let's make it easier to build that new housing. Let's create protections for people so that they're not going to get displaced from their homes. But let's make it so that this new housing can get built so that they don't get displaced. That's the solution. The solution is build a lot of housing.

Samantha Hancox-Li [55:31]

My last question for you is, as an organizer, as an activist, as someone who's trying to create political change, what would be your biggest piece of advice for listeners of Neon Liberalism if they want to try and make change in their own city and try and get housing working better in their city?

David Vatz [55:48]

One of the best lessons that I learned with this entire process is just go do the damn thing. I think sometimes just getting started is the hardest part.

This group that now has several hundred people involved, and we have meetings with public officials, and we've produced research, and we've clearly impacted the public discourse on this topic - it started because I heard people complaining about building new housing, and I was like, "Hey, my three other friends, let's go speak at this public meeting, and let's say that we're in favor of this." There's going to be this meeting where 20 people are going to speak against it. Let's be the voice in favor of it. And that was it. That was truly the beginning of it. It was a text message thread with me and a few friends, and we went and we spoke.

Following that, we heard from some of the leaders who were at that meeting, and they said, "Thanks for doing that. We never hear people say we want new housing. We always hear people saying it's going to impact traffic, it's going to impact parking, it's going to block my view, this and that and the other thing."

From there, it was mostly just a continued, slow build. At that point, we didn't have the name of our group. We were just people speaking in favor of a project. The next time we did it, we had the name for the group, and people said, "Oh, what's Pro Housing Pittsburgh? How can I get involved?"

We graduated from a text message thread to a WhatsApp group, and then it kept growing. Then we had our first in-person event, which was just a Saturday afternoon meetup where we said, "Hey, everybody, come and let's talk about how we keep doing this." And then we graduated to Slack from WhatsApp, because we kept getting bigger.

I think you just have to start somewhere. You can't go from zero to 500 people. You have to go from zero to five to 10 to 15. And then just slowly, keep making those inroads.

Samantha Hancox-Li [57:35]

You're not a professional activist. You don't make your living from politics. You have a regular job. I think that's really inspiring, in a way that there's a real hunger in America for doing something about housing.

And you who is listening to this right now - you can start doing it in your own town, in your own city. Find a meeting - a zoning meeting or a development meeting. They are happening all around you. Just go to one. Go to one and talk about housing. You can make a difference.

David Vatz [58:09]

Go to one, and then go to the next one, and then go to the next one. Eventually what you'll find is, whether it's your city councilors or your commissioners, whoever it is that you're speaking to, they'll start to notice it. And they'll start to notice, "Hey, here's this normal, thoughtful person who's saying they want this common sense thing to be fixed," and they'll want to work with you on that.

A lot of times, public officials hear a lot of ranting and raving from people who are upset about things. What we strive to be is regular people who just want to see some change. We're going to talk to you about it regularly, and we're going to spend the time and put in the effort to build the relationship over time. We're not going to come scream at you in your office. What we're going to do is just be present all the time, and continue to talk about these issues and continue to talk about why they impact us.

Samantha Hancox-Li [59:00]

I'm going to have some charts and some graphs and some white papers, some evidence and some explanations.

David Vatz [59:17]

We're providing something that is of value to the local leaders. We're providing information about topics that they might not understand that well. We're providing the ability to come and support initiatives that they might care about. If you're having a public meeting, you don't want to have a public meeting and have everybody say, "No, we hate this."

So we're helping them with things that are important to them, we're also helping them to become better informed on the topics. Hopefully the outcome of this is that we get good policies passed, and we get more abundance in housing in the area, and everybody is able to live where they want to live, and is able to do so affordably.

Samantha Hancox-Li [1:00:00]

I agree with that entirely. In these times, it can be very easy to fall into a bit of despair, a bit of doom scrolling. Things seem to be happening at the federal level that are incomprehensible and probably very bad.

Housing is something that can also feel kind of incomprehensible - it's so complicated, and there are so many different laws and so many different municipalities, but that also means it's something that we can get our hands on. It is close enough to you that you can make a difference.

We had better start making a difference. If we want to prove to the people of America that we can be trusted with governance, that we have a better future on offer, that starts in blue states and blue cities.

David Vatz [1:01:08]

That's so critical - this idea of having a positive vision of the future instead of a negative vision of the future, having positive things to say, not always grievances.

I think that's actually something that's really important to the YIMBY movement in general. The YIMBY movement is a positive and aspirational movement. It's a movement that says we want everybody to be able to afford to live in San Diego or LA or New York or wherever it is you want. We're not saying you need to be stuck in the same neighborhood that you grew up in for the rest of your life, and there's nothing wrong with that if that's what you want. But what we believe is that people should have options, and that there's this future of abundance where everybody can have what they want and can do so affordably.

I think that's really powerful. When so much of politics is dominated by grievance and negativity right now, being positive is really powerful.

Samantha Hancox-Li [1:02:09]

That's exactly right. David, thank you so much for coming on the podcast. If you happen to live in Pittsburgh, go on over to - I believe that's the website.

David Vatz [1:02:23]

Pro Housing PGH dot org, actually, but you can probably just Google it too, and it'll get you the right place.

Samantha Hancox-Li [1:02:29]

That's probably right. So ProHousingPGH.org, or just Google "Pro Housing Pittsburgh," to find some of the upcoming events, or get hooked into the community. Look into your own community and see if there is a YIMBY group around there.

Meanwhile, here on Neon Liberalism, we will continue trying to chart out that brighter future that we've been talking about, something to work towards, not just work against.

Thank you again for listening. As a reminder, Liberal Currents and Neon Liberalism are listener supported publications, so if you like the work we do here, going over to LiberalCurrents.com or Patreon.com/LiberalCurrents and subscribe. Thank you so much, and I will see you all again next week.