Secular Democracy: A Medieval Idea

Within the Manuscripts Department of the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles resides one of the masterpieces of the medieval age of illumination: the vaunted Stammheim Missal. Dating to the late 12th century, the Missal figures importantly in the Getty’s manuscript reliquary as a testament to the workmanship, artistry, and scholarly tenacity that marks an era otherwise unfairly known as the “Middle Ages”—an epoch of relative darkness situated between the dual sunbeams of Classical and Renaissance enlightenment. However, one particular leaf of the Missal conveys, at least symbolically, a sense of the formative—indeed transformative—nature of this dynamic time in European history. The Creation of the World, as it is known to us, features a stunning motif: the visage of the risen Christ overawing a vividly colored roundel depicting the six days of creation as told in the Book of Genesis. It remains a powerful emblem of a time known for its piety and dogmatism.

Indeed, a new world was being created in the Middle Ages. But it was a world in which the risen Christ Himself would face the earliest challenges to His suzerainty over European political life. Buried within the deferential religiosity of the medieval world can be found the first kernels of a radical new concept: secular governance. It is well known that the Late Middle Ages, well after the Stammheim Missal’s time, was fraught with theological insurgency. It was the era of John Wycliffe and Jan Hus, the “heretical” forerunners of anticlericalism and Reformation theology. But secular postulation was an altogether different beast. Indeed, secularism’s unlikely medieval provenance accentuates an era of decisive intellectual animation and avant-garde political theorization, characterizations we today do not typically associate with the Age of Faith. In truth, it was a time ahead of its time, a realm out of its own element.

The chief prophet of this subversive conception of the political good may be one of the most significant thinkers most people of today’s world have never heard of: Marsilius of Padua. Born in Padua sometime in the early 1270s, Marsilio dei Mainardini remains to us a relatively ephemeral figure for one whose political scribblings can be said to have established a nascent bedrock for modern Western secularism. His early schooling was at the University of Padua where he may have studied medicine. In 1313 he would become rector of the University of Paris, at the time Europe’s most prestigious institution for the study of philosophy and theology. Like so many medieval and Renaissance scholars of great minds and greater egos, he would Latinize his name to lend it the Classical gravity of a Cicero or a Seneca. Since his biography thus far is sparse, we have a limited ability to penetrate Marsilius’ psyche so as to understand why just over a decade later he elected to raise his quill against that most sacrosanct of institutions, the Latin Church.

Defensor pacis and the secular state

On June 24, 1324, Marsilius completed his only great work, Defensor pacis (The Defender of Peace). The background of this tract, like its author’s, is murky. Indeed, there are scholars who doubt that Marsilius alone wrote all of it. However, what cannot be denied is its radical remonstrance of the authority of the Holy See, the one establishment that bound an otherwise fractious medieval Western Europe into something resembling a corporate whole, a “Christendom.”

Written in the throes of a dispute between Pope John XXII and Louis IV, Holy Roman Emperor, Defensor pacis asserts a defense of the prerogatives of the latter against those of the former. Louis’ path to power was a difficult one. After a series of disputed elections to fill the vacant Holy Roman throne, civil war erupted between Louis and the Duke of Austria and Styria Frederick the Fair, the Habsburg claimant. Louis’ final victory in 1322 did not settle the matter, however. The pope brazenly refused to ratify his election as emperor and excommunicated him in 1324. The stage was set for yet another conflict between the papacy and the Holy Roman Emperor, a recurring motif of medieval politics. Herein lay the peace that intrafaith quarrels broke, the peace which Marsilius sought to “defend.”

Against this contentious backdrop Marsilius penned his provocative thesis. Structured as two long discourses and a much shorter third, Defensor pacis challenged the concept of Plenitudo potestatis (the plentitude of power), an assertion of papal absolutism in matters both spiritual and temporal that had been wielded by pontiffs in various forms since perhaps as early as the 5th century. In a 1302 bull (a papal decree) entitled Unam sanctam, the pope illustrated this dual power through the allegory of two swords, the spiritual and temporal. “Both swords,” said the bull, “are in the power of the Church.” Secular rulers wielded the latter only by the “will and sufferance of the priest [read as bishop or pope].” This secular power was thus leased but never truly owned.

Marsilius begged to differ. The Church, he argued, possessed no such temporal sword. His logic dictated that the efficient causes of the worldly state “are the mind and wills of men through their thoughts and desires, individually and collectively.” Humankind as a whole, in Marsilius’ conception, received a mandate to contrive its own politics from its maker, not from a papal ordinance or clerical concession. Though not to be confused with the expression of “divine right” utilized later by 17th century monarchs, the gravity of this statement must be appreciated.

Strangely enough, it was from scripture and the early Church Fathers that Marsilius derived this motion of clerical impotence in the secular realm. Paul’s Second Epistle to Timothy admonishes the “soldier of God [who] entangleth himself with secular affairs,” a notion reinforced by Saint Ambrose of Milan and Saint Augustine of Hippo, the theological titans of the late 4th and early 5th centuries. In the Latin Church’s most cherished personalities Marsilius found some of his strongest, if most unlikely, allies.

From Gregory the Great to Bernard of Clairvaux, Marsilius’ Second Discourse sought out defectors within the Church’s intellectual past to aid in his cause. At the heart of his Bernardine discussion in particular was a notion key to the Marsilian conception of secularism: secular supremacy over the church.

Here, Marsilius remarks that Bernard appended an epistle to the Bishop of Sens with a crucial disclaimer to all ecclesiastical claims to worldly jurisdiction: “For Christ avowed that even over himself the power of the Roman ruler had been ordained by heaven.” Indeed, ecclesiastical authority does not even constitute true jurisdictional prerogative and claims to such are, Marsilius shamelessly asserts, antithetical to the laws of God. There is only one state in a realm and that is the state. Here could be found no “separation of church and state” with which Marsilianism should not be confused. Rather, it was the dominance of the latter over the former that Marsilius sought.

The authority the medieval Church claimed ownership of lacked a scriptural abutment, according to Defensor pacis, and had no coercive ability to enforce in any regard. Indeed, it could not enforce its own divine law even if it was of a right to as Marsilius went on to make clear:

[an ecclesiastical authority] neither should nor can compel anyone to such observance in this world by any pain or punishment in property or person; for we do not read that such power to coerce and govern anyone in this world was given to him by the evangelic Scripture, but rather that it was forbidden by counsel or command, as is clear from the present chapter and the preceding one. For such power in this world given by the human laws or legislators; and even if it were given to the bishop or priest to coerce men in those matters which relate to divine law, it would be useless.

But who were these “legislators” and to whom did they answer? It is time to turn to the most surprising aspect of Defensor pacis regarding how Marsilius legitimized his new world order unmoored from the dictates of the Church.

Marsilian democracy

It must be quickly noted that Marsilius’ politics were explicitly not agnostic but anticlerical. Indeed, as we have seen, God played a central role in his arrangement of power and jurisdiction. His was still a world in which legitimation by the divine was paramount to ordering politics justly. But Marsilius added another layer to this process of legitimation: popular sovereignty. The legitimate state was detached from the dominion of churchmen and instead predicated on the will of the collective. In this, Marsilian politics planted the seeds of democratic politics or at least democratic theory.

To complicate matters, however, Marsilius himself explicitly denies the democratic nature of his thought at the onset of Defensor pacis. We must understand that in Marsilius’ day “democracy” was an unflattering, almost pejorative designation for almost any form of mass politics and so serious thinkers avoided it. Aristotle’s titanic presence in the scholastic world of late medieval Europe had much to do with this. His characterization of Athenian democracy, the benchmark of democratic governance at the time, was less than glowing. Marsilius therefore devised a distinctly Aristotelian tactic to outmaneuver this semantic hurdle.

In his First Discourse, Marsilius designates his brand of political ordering a “polity” wherein “every citizen participates in some way in the government or in the deliberative function in turn according to his rank and ability or condition, for the common benefit and with the will or consent of the citizens.” This he contrasts from “democracy” under which the vulgar masses legislate selfishly and sometimes without the consent of all of the governed. Here, Defensor pacis borrows from Book IV of Aristotle’s Politics in which a “polity” is said to constitute a marriage of oligarchic and democratic elements, though Marsilius seems to strongly prefer the latter. By doing this, Marsilius clearly meant to draw a distinction between his politics and those of the open air ekklesia of Classical Athens. Since Marsilius’ time, our definition of democracy has thankfully broadened and matured, allowing us to identify the strong strains of modern democratic thought in Defensor Pacis.

Marsilius’ embrace of a democratic idea of governance, however fluid, marked a bold departure from the Aristotelian consensus of the scholastics whose intellectual forbearer, Thomas Aquinas, was made famous at Marsilius’ own University of Paris some six decades before. Indeed, the medieval tumults incurred by ecclesiastical intervention in secular affairs were a “cause of strife” which “Aristotle could not have known.” The infamously antidemocratic Aristotle was thus blind to a problem for which democracy provided a solution. A divinely ordained church would—and should—be supplanted by a divinely ordained “legislator,” a human actor working for the civic good.

This concept of the legislator humanus, the human legislator, was developed, along decisively voluntarist lines. Though the divine will sanctions civic life, it is the human will which shapes it. This legislator is thus granted by God the prerogative to order his or her own world. But is the legislator an individual? A body? An institution? Marsilius does not bother with the details as such. He is ever the theoretician. He does, however, make clear that the legislator is a collective, defined in this well-known passage as:

…the people or the whole body of citizens or the weightier part thereof through its election or will expressed by words in the general assembly of the citizens, commanding or determining that something be done or omitted with regard to human civil acts…whether it makes the law directly by itself or entrusts the making of it to some person or persons.

How this necessarily contrasts from his earlier unfavorable characterization of “democracy” is not quite clear. To us, it likely wouldn’t to any significant degree. For Marsilius, popular sovereignty rules the day. This is a boon that the Church cannot obtain. Its Pope rules without scriptural prerogative over a world he cannot control. Its bishops prevail over their metropolitan sees absent the consent of the legislators therein. Marsilius’ secularism was thus inextricably bound to his democracy, his “polity.” The 14th century would never forgive him.

The creation of the world

Marsilius of Padua died around 1342. The Latin Church knew immediately that he was more than a troublesome canon with a busy pen. He was driven from his native Italy and entered the service of the imperial court of Louis IV where he spent the balance of his career forcibly bringing the Bavarian clergy into line. He seems to have practiced what he preached.

The world he helped create would be drastically different from the one that spawned the Stammheim Missal. Deference to an ecclesiastical order said to have descended from Saint Peter would one day cease to be universal. His writings would even be used to forward the Henrician Reformation in the 16th century. But Marsilius’ afterlife is not bound solely to the pages of his tract. Our civic spaces today bear a Marsilian likeness and an understanding of the proper nature of the state that was conceived in a 14th century mind.

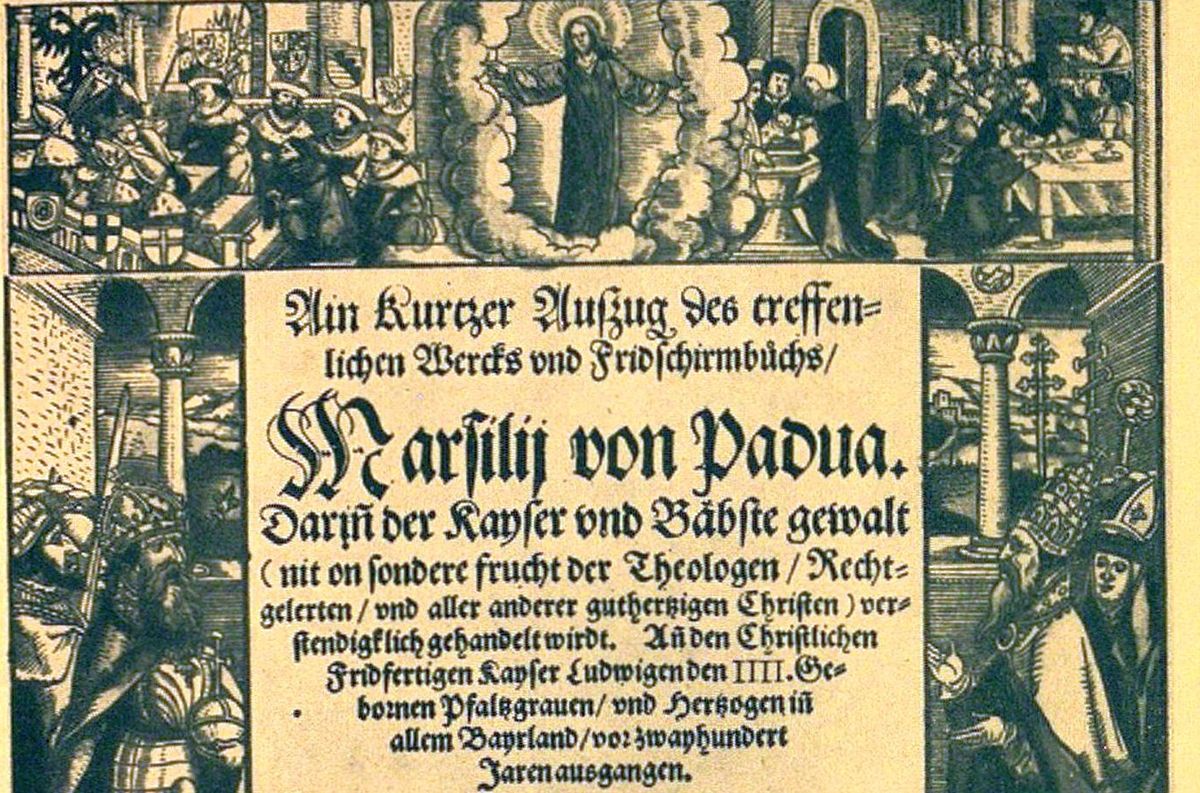

Featured image the title page of the German partial translation of the Defensor pacis printed at Neuburg