Selective Acceptance of Settled Norms: Tristan Rogers' "Conservatism: Past and Present"

Rogers has written a useful guide to the western conservative intellectual tradition that runs into trouble when it approaches the conservatives of our day.

Russell Kirk opened his classic The Conservative Mind with “the stupid party: this is John Stuart Mill’s description of conservatives.” In fact, Mill was more emphatic, insisting that “stupid people are generally conservative.” A reputation as the stupid side of the political spectrum has dogged conservatives for generations. Anyone who has listened to the other conservative Kirk, Charlie, or read Gad Saad’s The Parasitic Mind will know it is a reputation right-wing influencers don’t mind vindicating. But it is a serious mistake, historically and strategically, for liberals to think that conservatives are inherently stupid. Some of the most sparkling intellects in the philosophical canon—Burke, Nietzsche, Scruton and Hayek—were men of the center-right and right. Sadly, the tradition of right-wing thought remains little known to liberals and leftists (though in fairness, anyone who has read conservative takes on “Marxism” or Mill will know things are often worse on the other side of the spectrum). Which is a shame since there is much to be learned from it, including “knowing our enemy” as the podcast goes.

Tristan Rogers, a teacher at Donum Dei Classical Academy, has just published an eminently readable and helpful guide to Conservatism: Past and Present. The first half introduces readers to many of the seminal figures who have influenced conservative thought: Aristotle, Augustine, Hume, Burke, Hayek and Scruton. By and large, it is an erudite and careful exegesis which anyone can read with profit. Rogers deserves a lot of praise for his helpful and scholarly contribution. The second half of the book is effectively a defense of modern (American) conservatism, aiming to further defend the tradition’s ambitions in an intellectually satisfying manner. Here I think the book runs into issues, even if the quality of argumentation is of a high level.

The conservative canon

Rogers opens his book by discussing “dispositional conservatism,” which “resists change, not on intellectual grounds, but from a felt threat to the things we collectively (and individually) cherish.” In The Enforcement of Morals, Patrick Devlin described dispositional conservatism as the attitude of the “man on the Clapham omnibus” or the “right thinking man.” In American parlance we might call him the bar stool conservative. A dispositional conservative is a right thinking man since he does not necessarily reason about why he holds the views he has, and indeed might be acting entirely on prejudice and instinct. But Devlin insists that does not mean that the dispositional conservatives’ views are simply wrong, since in fact it is the common moral prejudice of a society that holds it together.

While sympathetic to dispositional conservatism, Rogers instead presents his book as a contribution to “philosophical conservatism.” Philosophical conservatism is committed to the “search for human happiness” which takes place within “a political community oriented toward the human good.” Consequently, it does not rely on unthought prejudices and an instinct for conservation—although Rogers insists unlike liberal and left philosophers, it does not arrogantly dismiss them either. Philosophical conservatism is, in part, a defense of dispositional conservatism at a higher level—offering “reasons” for why it's okay that the dispositional conservative doesn’t have or need reasons, to paraphrase Roger Scruton.

In its more ambitious modes, philosophical conservatism goes further in trying to answer age-old questions about the nature of justice and the good, while recognizing the limitations of reason. This (alleged) “moral and epistemic” humility is why philosophical conservatives believe that “beneficial change must begin with (and within) the existing institutions and culture of a society.” It inclines many philosophical conservatives, especially the ones Rogers admires, towards a kind of “traditionalism” that is a “middle position” between endorsing too much social authority or too much liberal libertinism.

By and large, Rogers’ discussion of the history of conservative thought is at a very high level. Over the course of almost 150 pages Conservatism: Past and Present surveys the major thinkers of the canon and situates them in relation to one another while defending their contemporary relevance. The sections on Robert Nozick and Roger Scruton are especially interesting to a modern reader, introducing the more right-libertarian and traditionalist wings of conservative thought. Rogers acknowledges the frequent criticism of Nozick that he simply asserts the existence of rights without providing a foundation, but rebuts that there was a widespread “postwar liberal consensus” on the importance of rights available for Nozick to draw upon to legitimate his claim. He emphasizes Nozick’s insistence that there is an “inherent conflict between liberty and equality,” because if individuals are left free to make choices about where to spend their money it will inherently disrupt any egalitarian “pattern” of justice imposed upon society.

While sympathetic to Nozick’s arguments for property rights and capitalism, it's pretty clear Rogers’ heart is with Scruton’s traditionalism. Scruton himself had an ambiguous attitude towards Nozick-type arguments for natural rights, since those arguments tend to have an inescapably liberal quality. Sometimes Scruton defended a Burkean approach to rights as social conventions, while in The Soul of the World he comes close to affirming the existence of natural and negative rights based on people's need to be left alone. Rogers is clearly more fond of the former Scruton, noting that his “conservatism is not fundamentally opposed to political authority. A conservative is disposed to conserve the established political order. He is motivated by an ideal of social unity, not freedom.” As Scruton himself put it in The Meaning of Conservatism, it is “allegiance” to authority that ties society together, not excess respect for the rights and interests of its mortal members.

My only major complaint with the first half of the book is not everyone Rogers is determined to canonize necessarily fits the conservative label. He follows Kirk, George Will, and others in reading the American Founding Fathers as by and large conservatives who defended a “mixed regime” predicated on a realistic vision of human nature. But Rogers is troubled by the fact that, of course, the American Founding Fathers were also revolutionaries who inveighed against the “Tories” of their time. Rogers tries to square this by insisting that their revolution was nonetheless conservative since it by and large retained the “existing regime” rather than replace it. They were “secessionists seeking reform rather than vicious seditionists seeking revolution.”

This attitude is hard to square with the fact that, by any metric, the American colonies in the 18th century were amongst the freest and most prosperous communities in the world. If revolution can only be justified under extreme circumstances, from even a moderate conservative standpoint it is very hard to make a case that colonists in a foreign land rebelling against paying taxes on tea to pay for their defense were anything but insurrectionaries upsetting the established order. Moreover it is certainly not the case that the Founding Fathers simply retained the “existing regime.” As Sheldon Wolin points out in The Presence of the Past, they were revolutionaries twice over. First, overthrowing their despotic but hardly tyrannical government, and then replacing the country’s original constitution with an entirely new one.

This, in turn, transformed the nature of American law, transitioning it from a largely common law system to one defined by what Aziz Rana calls a borderline “creedal constitutionalism” unique in its fetishism. Moreover, on a conservative reading the initial American constitution can’t even be framed as a success story since in spite of its enormous moral compromises a major civil war broke out within a lifespan. This led to enormous social upheaval and a further, transformative “Second Founding” which in turn was sufficiently compromised to pass the buck on social problems to subsequent generations. Had the Founders been more radical than the revolutionaries they already were this might have been avoided.

But the most egregious example of attempted canonization within the conservative tradition is Plato. Many conservatives quite rightly admire Plato for his insistence that there are eternal forms of the good which we have duties to align our soul with, since this cuts against the alleged liberal and left view that individuals should be left free to live their subjective truth. And of course there is a longstanding conservative appreciation for Plato’s critique of democracy. At the same time it’s hard to deny that Plato can very easily be read as a or even the utopian thinker. A radical who imagined that his kallipolis would be ruled by philosopher kings who would mandate an end to strict property divisions and raise the children of guardians in common. Karl Popper famously read Plato as a proto-communist defender of the “closed” authoritarian society. Plato’s Socrates also struck many as a proto-critical philosopher, who relentlessly undermined faith in the gods and goodness of the city and was a fierce critic of the doxastic prejudices of his fellow Athenians. Certainly conservative Willmoore Kendall thought so when he called Socrates a “revolutionary agitator” who the elites of the city were right to put down.

Rogers works very hard to dispel this latter Plato. He offers a Strauss-like take that Plato never took the argument developed in The Republic to be a “feasible political theory.” Instead the esoteric lesson of the book is a cautionary tale about the dangers of utopianism. This would be an extremely radical way to read a seminal work of Western thought, which would amusingly deflate the entire canon erected around Platonism in a puff of Socratic irony. Unfortunately Rogers offers very little to justify reading Plato’s Republic this way beyond the fact that he finds many of its conclusions distasteful. Somewhat frustratingly, Rogers seems aware of this; initially presenting such an odd reading as a mere “intriguing possibility” before taking it as demonstrated truth for the rest of the book.

There is an attempt to argue that since the education required for philosopher kings could only be carried out in a just city already ruled by philosopher kings, Plato couldn’t possibly have meant to endorse the ideas presented in the book. But that seems very easily rebutted by the fact that Plato himself clearly thought one could offer a quality education to elite youth even in a very imperfect city like Athens, since that is exactly what Socrates and he himself did. Rogers also points to Plato’s allegedly more realistic dialogue, the Laws, as evidence he was not a utopian thinker. But as David Lay Williams notes in The Greatest of All Plagues, even in the less overtly radical Laws Plato was still calling for transformative proposals to secure a “relatively equal wealth distribution” by limiting inheritances, forbidding the buying and selling of landed property, banning the possession of gold and silver in a private capacity, and more.

My suspicion is that Rogers simply really likes Plato and is keen to attach his prestige to the conservative canon. The former impulse is admirable; there is, of course, much to be gained from reading Plato. The latter seems simply implausible to me, and an instance of trying too hard to shove an ancient thinker who did not know or share our political orientations into a box where he does not fit. Rogers would be better off simply doing what most of us already do: draw lessons of value from Plato while admitting that many of his core insights warrant criticism and are sometimes hard to apply to a modern context.

Defending modern conservatism

The strongest parts of Rogers’ book are the historical sections. My criticisms of his readings of the Founding Fathers, Plato, as well as Tocqueville and Hegel (both moderate liberals) is in no way a dismissal of the strong scholarship on display throughout the book’s first half. Anyone with an interest in learning about the conservative canon, or the “great tradition” as Scruton once put it, should pick up Conservatism: Past and Present. What is sure to be more controversial for some is the application of philosophical conservatism to contemporary problems. Rogers describes conservatism as a moderate position, committed to the cautious management of change and unafraid to use mild authority—whether cultural or via the state—to pursue human happiness and the common good. As he puts it, the “conservative disposition limits any effort to promote the good in ways that exceed human nature and the constraints of reality.” Change must begin within existing institutions and culture.

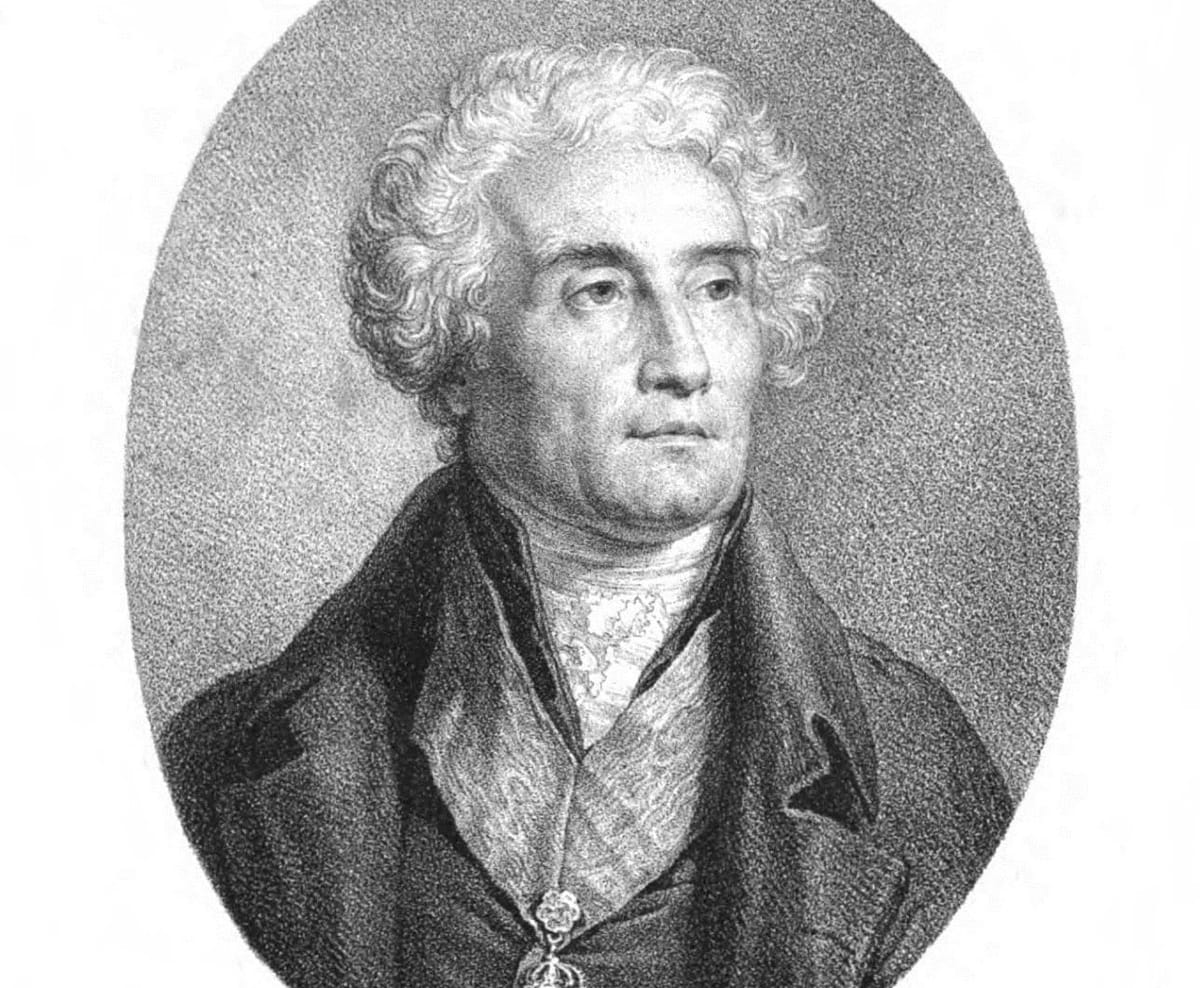

The problem with this is how difficult it is to square with actually existing conservative practices, historically and in the present day. Counter-revolutionaries across Europe were far from seeing the French Revolution as an organic evolution towards freedom. Many followed De Maistre is musing that providence had ordained that millions of Frenchmen must die for the crime of executing Louis XVI and waged wars to roll back the rising tide of popular discord. That this was often done in the name of prudence is profoundly unconvincing in 2025 given that only the most reactionary would accept 18th century arguments that ceding basic rights to freedom of expression and assembly to the masses would lead to disaster. In this respect conservatives were simply wrong about what human nature and reality were capable of, and we are all the more fortunate for it.

Margaret Thatcher insisted her goal was nothing less than to “remake the soul” of the nation, and economics was just one means to do it. To do so she upended the post-war consensus around a robust British welfare state, initiating what many have called a revolution which sought radical transformations of the sort needed to make the world safer for capitalism. This was followed up by British Conservatives taking the dramatic step of bringing the UK into the European Union, before following that act with an equally dramatic Brexit. Ronald Reagan also famously initiated the “Reagan Revolution” and was fond of quoting the most ultra-radical of the American revolutionaries, Thomas Paine, who suggested humanity had the ability to fundamentally reshape the world. During the Bush Administration, neoconservatives like Karl Rove dismissed the “reality based community” and opined that imperial power could remake the world. This led the Bushites to the rather un-Burkean view that one could remake entire societies at the cost of hundreds of thousands or lives. Scruton notably approved.

And of course in the current day Trumpism has very much rocked American democracy. From denying he lost an election he clearly lost to provoking the January 6th riots, Trump I was as far from prudential as it is possible to be. The second Trump administration hit the ground running, launching a sustained assault on the Federal government, proffering completely new interpretations of the 14th Amendment to put an end to birthright citizenship, promising mass deportations by the millions, disintegrating old alliances by threatening dangerous countries like Canada, Panama and Greenland with annexation, and of course smashing the global economic order that was itself very much the product of center-right neoliberal efforts. The list goes on and on.

Rogers admirably acknowledges much of this, pointing out that conservatives have good reason to criticize such “flagrant display[s] of populism” as we saw on January 6th. But he thinks some populist zeal is defensible given that our society is not in a “state of health,” which means that a “destabilizing force” will be required to “recover the health of the political order. Prudence, therefore, counsels to treat the symptom while paying attention to the underlying causes. As I have argued, it is better for conservatives to embrace populism so that it can be moderated or directed toward the right ends, rather than to ignore or try to stamp it out.”

The problem is Rogers’ own positions are often anything but “moderated” or indeed even about preventing change. Destabilization seems to be aimed not just at standing athwart history yelling stop, but a counter-revolutionary zeal to “recover” or “retvrn” to an imagined past through what Patrick Deneen defends as overt “regime change” to challenge liberal hegemony. Such regime change often runs counter to the common sense views of Americans Rogers in other contexts tries to defend.

To give a clear example, the vast majority of Americans now accept same sex marriage at record high levels. Rather than seeing this as a widely settled norm, or even insisting he privately disapproves but accepts the right of people to be left alone, Rogers thinks we should “consider same-sex marriage no more than a tactical truce” which has “already borne unforeseen costs.” Despite the aforementioned polls, Rogers still insists there is an ”intensely felt need and desire to return to the traditional” on these matters, which warrants reviving another divisive debate. The social disunity conservatives always resent be damned. “Reality comes first,” according to Rogers, which one would think would inoculate him against defending a President who has told tens of thousands of lies and counting.

The prudence of the left

This brings me to my main point. I think Rogers is right to say that there are forms of conservatism which are inherently moderate, prudent, and cautious. But none of those are qualities which are essential to conservatism, let alone the broader right. By any historical metric the Nordic Social Democrats and socialists were prudent and cautious while implementing reforms to build a far more democratic, egalitarian and (let’s face it) empirically successful form of society than what we see in the United States. Nor is conservatism based on a rejection of what Rogers calls “liberal abstraction[s]” since many of the notions conservatives appeal to—such as the nation or the “West”—are extremely abstract reifications and imagined communities.

The essence of conservatism and the broader right lies, as Hayek wrote in “Why I Am Not A Conservative,” in the belief that there are recognizably superior persons in society who are entitled to greater agency, wealth, status, and political clout. In moderate forms this can be reconciled, as Rogers notes, with a commitment to democratic and liberal principles. But as Corey Robin argues in The Reactionary Mind, when conservatives feel that liberals or the left have been “in the driver's seat” for too long they are pushed by their own agency to reject an unworthy present and adopt the future as their preferred political tense. This will be a future where we will once again recognize, as James Fitzjames Stephen put it, that to obey a real superior is a great virtue. And the multitude better remember it.

Such an outlook is ultimately incompatible with the liberal and for that matter socialist conviction that all persons are moral equals and only a more or less egalitarian society is compatible with taking seriously our obligations to morally and spiritually respect the sacredness of each person’s life. I follow Charles Taylor in regarding this as an ethically higher outlook than conservatism because it is more demanding. But liberal and socialist convictions are by no means self-evidently true, as the best thinkers in the conservative canon have always reminded us through their probing objections. This is why it is extremely valuable that we learn more about the conservative canon, and why readers would benefit from picking up Rogers’ thought provoking book.

Featured image is Lithograph of Joseph de Maistre, by Pierre Bouillon