The Case Against Dictatorship

The problem with democracies is that they are sclerotic, indecisive, and dithering; by contrast, states ruled by strong and capable dictators are capable of rapid policy change–or so it is argued. As one prominent critic puts it, democracies “are inherently reactionary and absolutist” compared with dictatorships, which “accept the most daring political and social experiments.”[1] Certain events seem to bear this perspective out: in America, a pioneer of liberal democracy, our representatives regularly struggle to perform basic tasks like agreeing on a budget. In Israel—another liberal democracy, but with very different institutions—such difficulties have led to elections being held with comical frequency.

Meanwhile, it is China’s system, rather than a monarchy or the fascist state, which stands as the alternative to liberal democracy. In 2020, The Atlantic ran a defense of China’s massive Internet censorship regime, mere months after their heavy-handed and flat-footed response to the COVID-19 outbreak allowed the novel virus to escape and become the world’s problem. Yet as liberal democracies struggled with the consequences of this for the years that followed, China was largely praised for its willingness to lock down large population centers to an extent most other countries had little political appetite for.

Now, however, China has failed to vaccinate their vulnerable elderly population to any great degree, while those who have been vaccinated have received a markedly inferior product. Their lockdowns have grown more and more intense as the contagiousness of COVID has increased by leaps and bounds; for this and other reasons, US GDP will actually grow more in percentage terms this year than China for the first time in my lifetime. Russia, meanwhile, has spent the year on a failed and pointless invasion for which they have paid a substantial cost in national wealth, geopolitical strength, military hardware, and human life.

Regimes blunder; this is not unique to China or Russia, or to non-democracies in general. But contrary to Mussolini and less nefarious critics, liberal democracy does have important structural advantages over its rivals that are too often overlooked.

One reason for this oversight among even its friends is that liberal democratic ideals are so dominant today. Today, nearly every country in the world is either a liberal democracy or to some degree pretends to be. As of 2013, 90 percent of the world’s population lived “in independent states with constitutional documents that asserted their democratic character.”[2] Moreover, most of these assert their liberal democratic character in particular; even North Korea’s constitution promises “freedom of speech, of the press, of assembly, demonstration and association.”[3] Even Mussolini himself, while rejecting that “numbers, as such, can be the determining factor in human society” or the right of “numbers to govern by means of periodical consultations” nevertheless felt compelled to portray fascism as “real democracy.”[4]

Understanding the practical strengths of liberal democracy paradoxically requires a bit of demystification. North Korea may present a stark example, but even in the best cases liberal democratic ideals soar far above the reality on the ground. Ideals are abstracted from the messy details of life; they can be used to judge just about any sort of regime or society, at any point in history. But the liberal democracies that exist today, even as varied as their institutional particulars may be, share a family of key traits. They are a particular type, which developed under particular conditions, and which may not be possible absent those conditions. Their pioneers may well have held liberal democratic ideals or older, related ones, but they needed more than ideals to navigate the political realities of their day.

Among those realities was the development of a citizenry who are “modular,” able to form links between one another “which are effective even though they are flexible, specific, instrumental.”[5] This quality emerged as part of the global transition from agrarian to commercial societies. After all, modularity is wonderfully useful for investors, business owners, and employees, and for the many who enjoy the social benefits that result from the contractual and financial links these groups form. It can be troublesome for regimes, however. After all, the average country has a population in the tens of millions; it doesn’t require a very large fraction of these modular millions to link together and cause serious trouble for the governing class.

Every society faces crises due to natural disasters or disease, or even due to social change that is on the whole positive, such as economic growth. These crises produce broad unrest among the highly capable “modular” masses, as well as among elites. Liberal democracies have the mechanisms to see the signs of unrest before it erupts, and to act decisively in response to this information. By contrast, the very means by which non-democracies insulate incumbents from competition sabotages their ability to understand and respond nimbly to changing circumstances.

Flexible, responsive, and effective

During the debates over ratification of the American Constitution, the anti-federalists made the case that republics had historically been very small, and that a geographically large one could not be sustained. James Madison famously argued for the virtues of an “extended republic,” but what was lost on both parties is that the primary reason republics had been small in the past is that it could not have been otherwise.

Our world is very different from the one that the old republics and monarchies existed in. In the agricultural societies of the pre-modern world, it would have been quite difficult to send representatives from New Hampshire or Georgia to Washington, DC, and harder still for voters to find out what those representatives were up to. Today, voters in California or Oregon can send representatives to DC and keep up with events there practically the moment that they occur. Moreover, representatives in DC can write laws which can be communicated to officials and courts across the vast continental territory of the contemporary United States. Modern transportation and communication technologies enable a degree of centralization across enormous territories that was impossible until very recently in the history of the world.

As already discussed, the “modularity” of the modern citizen, stemming in no small part from the broad-based enrichment and access to technologies of coordination, creates a great deal of risk for regimes that outright ignore even very small interest groups. Genuinely open electoral competitions for government leadership with universal enfranchisement provides an institutional valve for the many interests and factions of a nation-state to exert influence, thereby discouraging extra-institutional measures. This is especially true of legislatures, which by their nature subdivide the electorate and thereby create representatives to negotiate on behalf of particular interests.

The chief distinguishing characteristic of liberal democracy is the way that the elected offices relate to the rest of the system. The lion’s share of non-democracies today hold elections too, but they are either rigged to some degree, or the offices themselves hold no real power. By contrast, as Joseph Heath describes, “a successful, well-administered, and reasonably responsive liberal state” is:

the product of an ongoing internal tension between an essentially technocratic executive branch, an elected legislature that is highly responsive to public opinion, and a judiciary endowed with important supervisory functions. (. . .)each brings its own considerations and concerns to the table, and policy is ultimately determined through the interaction that results.[6]

In a sense, voters choose officials who go on to use the executive branch to govern well on behalf of those very voters. This of course is a considerable simplification; Heath himself emphasizes the wide berth of discretion that actors in the executive branch effectively have in their daily decision making, in any regime type.

Nevertheless, the responsiveness of the elected officials in a liberal democracy and their ability to turn this into actually executed policy should not be underrated. Ari Berman for example cites the testimony of an Edgefield County, South Carolina council chairman on the effects of voting reform there:

We paved roads for the first time in the black communities, improved garbage collection, changed road signs, got blacks in every office in the court house, changed the land fill, got a black magistrate, and started a rural fire department.[7]

Once the electoral system was modified to be more responsive, these public benefits were quite rapidly invested in. The African American constituency’s vote was given teeth, and their representatives actually put the local government to work on their behalf.

Plainly a moral victory. In a non-democracy, such pockets of ignored populations in a country would remain so. But purely from the perspective of a regime’s stability and self-preservation, this sort of result has practical merit as well. While the Edgefield County African American population may seem harmless before the enormous power of a modern government, allowing even relatively small segments of the population to become marginalized and neglected risks creating a base for the regime’s opposition to mobilize in the future. In a liberal democracy, of course, this mobilization can be channeled through elections, potentially resulting in incumbents being removed from office peacefully. In a non-democracy it could contribute to bringing down the whole regime.

No regime type is guaranteed a particular practical outcome; be it economic growth, an uncorrupt bureaucracy, or effective pandemic prevention. All regimes will stumble, all types of regimes will at times get on the right track for some area or other. But liberal democracy has the best set of institutional arrangements to give it the best shot of getting to a good outcome, though it may involve no small amount of muddling through to get there.

If that sounds like a qualified defense, it is only so if the point of comparison is utopian. Liberal democracy holds unqualified superiority over all other actually existing regime types.

The brittleness of non-democracy

The myth of the dictator is of a man who is not held back by politics and is therefore able to act decisively on behalf of the public good. But politics is nothing more than the striving “for a share of power or to influence the distribution of power”[8] and the politics that a dictator must engage in to obtain power and to keep it thereafter is not only nastier from a moral perspective than the politics of liberal democracies, but also ties the dictator’s hands in a number of crucial ways. All regimes are constrained, but the constraints on all modern non-democratic regimes are systematically at odds with long term stability and citizens’ wellbeing.

The methods by which incumbents in non-democracies come to power are many. Some were elected by young or fragile democracies, and insulated themselves from competition after taking office. Some were military leaders who used their superior force of arms to take power from civilian leadership. Some were well organized outsiders who opportunistically seized power when the prior regime was weakened or vulnerable in some way. Some are selected through internal party procedures in a one-party state.

Once in power, they must take measures to stay there. The termination of electoral competition does not mean the termination of constituents that must be appeased; it simply means that those constituents represent a drastically narrower set of interests. Military dictators can be decisive indeed, when they are decisively pilfering the country to pay off their key supporters within the military itself. Party chairmen can be decisive when having competent officials arrested or assassinated to prevent the rise of any potential rivals.

In Sheena Greitens’ study of dictators’ intelligence organizations, she notes that “managing popular unrest is best accomplished using a unitary and inclusive internal security apparatus,” that is, an organization that is centralized and draws on the general population for its personnel. Securing a dictator’s position against coups by other elites, however, “calls for fragmented and exclusive coercive institutions,” that is, multiple organizations pitted against one another with tightly restricted membership.[9]

Coups are almost always the more imminent threat, and so most dictators will take measures to “coup-proof” their regime in the manner Greitens suggests. This keeps each agency dependent on the dictator’s goodwill, as they can be discarded for one of their rival agencies if they show themselves to be disloyal. The exclusivity of their membership keeps them segregated from the general population, making them unlikely to collaborate with them against the regime. But this very separation makes it more difficult to gather information about the population, and the pressure to prove themselves over their rival agencies can lead intelligence services to take unnecessary actions. The combination of a bias towards action with poor information makes it much harder to engage in “more targeted, pre-emptive, and non-violent repression” and the regime therefore ends up with “higher levels of and less discriminate violence.”[10]

This problem is most acute in personalist autocracies, “where one person rules(. . .) constrained only by the de facto power of other people, rather than by more or less impersonal rules, norms, or customs.”[11] Russia’s Putin is a contemporary example of this. By contrast:

[I]n China, after Deng Xiaoping’s death in 1997, formal rules and implicit understandings came to effectively limit the terms of General Secretaries of the Communist Party of China (CPC), and even during his lifetime party bodies met regularly to make policy[.][12]

Deng’s reforms enacted an institutionally constrained form of non-democracy, which are more successful and more numerous than personalist non-democracies. These may suffer from Greitens’ dilemma less acutely than their personalist counterparts. Nevertheless, these too face great challenges in gathering accurate information about their populations. While far from perfect, in a liberal democracy “polls, independent media, and the like provide a reasonably accurate” source of information about a regime’s level of political support among society’s factions. But for incumbents in non-democracies, “their very power gives many groups in the population incentive to hide their true feelings.”[13]

Almost by definition, non-democracies exercise substantial control over their national media. The line between non-democracy and liberal democracy, after all, rests to a great degree on the barriers that are set up against opposition groups. And one of the most common barriers placed is on the ability of opposition groups to publicize their criticisms widely or to get taken seriously by popular media outlets. The Peruvian government in 1990 kept itself in power through an extensive bribery ring of both officials and members of the media, but notably “bribes paid to TV stations were more than a hundred times the amount paid to politicians[.]”[14]

Both the barriers to electoral contestation in the institutional sphere and the barriers to public criticism in the information sphere come at a cost for the regime. While it may help them stay in power in the short term, it can leave them flying blind to the level of their true support among the population. Moreover, if state media makes claims that “habitually conflict with lived experience or deeply held popular values, or contradict other trusted sources of information,” then rather than shoring up the regime’s position it can reduce its credibility. As Xavier Marquez puts it:

[C]riticism can be a source of information about lower-level malfeasance, popular needs and desires, and general policy feedback(. . .)and allows [the regime] to modulate its own messages; and it also bolsters its own credibility on occasion. (. . .)A sophisticated information management strategy thus does not attempt to silence all government criticism, but instead tries to prevent criticism from escalating into potentially uncontrollable collective action.[15]

He notes that China’s public sphere “produces much criticism but little coordinated action.” The approach that 21st century authoritarians have by and large converged on, therefore, is not total control of the media, which in the era of the Internet is anyway impossible. Instead they must maintain a fine balance. Does anyone truly believe that such a goldilocks approach to information management is permanently sustainable? Indeed, China has just recently faced open protest of the regime, which they have responded to with a mixture of repression and concessions.

The bottom line is that those non-democracies that tend to be more successful and long lasting than others almost all emulate “the institutional repertoire of representative democracies, using parties and elections to their advantage, ditching obvious and ineffective propaganda, and learning to live with more open public spheres.”[16]

In other words, most of them come quite close to the line of being liberal democracies, and simply take measures to make it very unlikely that current incumbents will have to leave office. Can such a system truly live up to the hopes that critics of liberal democracy have for it? Would it not plainly import many of the problems of liberal democracy without the benefits of true electoral competition for the highest levels of authority?

Why bother?

No non-democracy is ever going to solve the problem of succession and peaceful transfer of power as thoroughly as liberal democracy does. Meanwhile, those non-democracies that try to have it both ways need to maintain several fragile balancing acts simultaneously in order to survive; is it so surprising that they frequently fail to do so? In China, not only has the information management regime failed to prevent the recent protests, but its current head of state has dismantled many of the institutional constraints set in place during the Deng era, moving the country towards a personalist dictatorship with all of the warts that regime type brings with it. China’s last such case did not work out especially well.

At the end of the day, if most non-democracies feel compelled to come as close to liberal democratic institutional arrangements as they can while still insulating incumbents from competition, and to characterize themselves as liberal democracies in their own official documents, one wonders what the case for dictatorship really is. Why settle for anything less than the real thing?

[1] Mussolini, Benito, and Giovanni Gentile. “The Doctrine of Fascism.” World Future Fund, September 1, 2022. THE DOCTRINE OF FASCISM. http://www.worldfuturefund.org/wffmaster/Reading/Germany/mussolini.htm

[2] Márquez, Xavier. Non-Democratic Politics: Authoritarianism, Dictatorship, and Democratization. London: Palgrave, an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, 2017. 22.

[3] Quoted in Ibid, 23.

[4] Mussolini, Benito, and Giovanni Gentile. “The Doctrine of Fascism.” World Future Fund, September 1, 2022. THE DOCTRINE OF FASCISM. http://www.worldfuturefund.org/wffmaster/Reading/Germany/mussolini.htm

[5] Gellner, Ernest. Conditions of Liberty: Civil Society and Its Rivals. Penguin History. London: Penguin Books, 1996. 100.

[6] Heath, Joseph. The Machinery of Government: Public Administration and the Liberal State. New York, New York, United States of America: Oxford University Press, 2020. 32-33.

[7] Berman, Ari. Give Us the Ballot: The Modern Struggle for Voting Rights in America. First edition. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015. 156.

[8] Weber, Max, David S. Owen, Tracy B. Strong, Rodney Livingstone, Max Weber, and Max Weber. The Vocation Lectures. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub, 2004. 33.

[9] Sheena Chestnut Greitens, Dictators and Their Secret Police: Coercive Institutions and State Violence (Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 17-18.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Márquez, Xavier. Non-Democratic Politics: Authoritarianism, Dictatorship, and Democratization. London: Palgrave, an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, 2017. 63.

[12] Ibid. 64.

[13] Ibid. 131-132.

[14] Ibid. 141.

[15] Ibid. 138

[16] Ibid. 243.

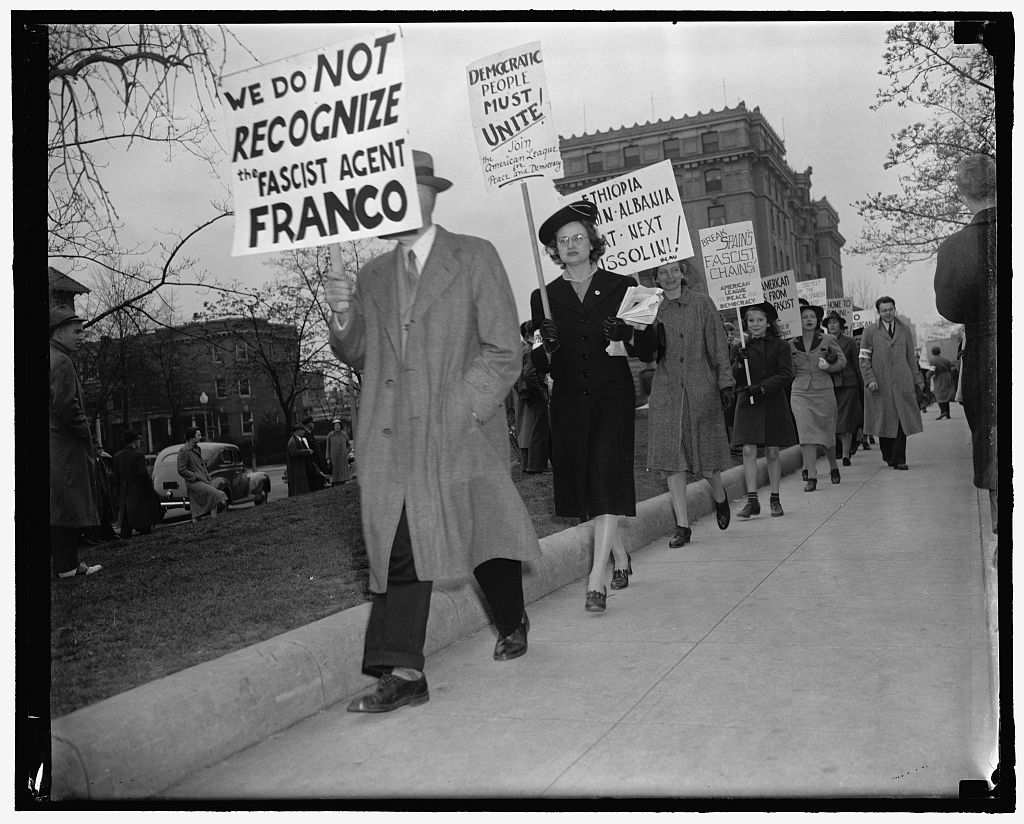

Featured Image is Protestors Hit Spanish & Italian Fascists in DC: 1939, by Harris & Ewing