The Dangers of Overestimating America's Power to Determine Events

In opposing US imperialism, progressives often emphasize US power. The logic here is straightforward; if the United States has great power to affect international events, it also has great culpability.

The problem, though, is that the focus on US actions and US capacity can lead to the conclusion that the US can fix global problems through unilateral action. That’s a conceptual frame which plays into the hands of militarists and interventionists who want the US to police the world with an infinite flow of boots on the ground. Progressives who want to end conflict and reduce global violence would do better to acknowledge limits to US culpability and to US power. There are many conflicts the US can’t resolve or ameliorate through force. That’s a strong argument for global deescalation.

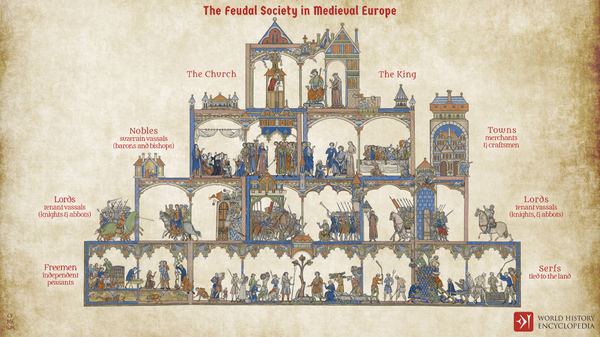

The statement on Ukraine by the Democratic Socialists of America, issued before the current Russian invasion, is a good example of the problems with framing the United States as the sole, omnipresent, and implicitly omnipotent presence on the world state. The document is a blistering condemnation of NATO expansion and US military aid to Ukraine and the region. “NATO is a mechanism for US-led Western imperialist domination, fueling expansionism, militarization, and devastating interventions,” DSA states.

As Harold Meyerson points out at The American Prospect, the DSA statement barely mentions Russia and doesn’t mention Putin at all. In the world described by the DSA, the US is the only aggressor, the Russian army on Ukraine’s border doesn’t exist, and Ukraine itself has neither aspirations nor will. There is no mention of the fact that Ukraine desperately wants to be part of NATO precisely because it has feared that Russia wanted to annex it. It hoped that a Western alliance would allow it to retain its sovereignty—and prevent war.

This vision, in which the US is the only effective actor and the people it acts upon have no internal politics or goals of their own, is a kind of mirror image of US imperialist justifications and ideology. Ukrainian appeals to the West for help are quietly sidestepped, just as Dick Cheney cheerfully ignored Iraqi opposition by claiming we would be “greeted as liberators.” The voices of US actors—imperialist or anti-imperialist, as the case may be—drown out any possible dissent. War or peace can be imposed unilaterally by the United States. No one else matters.

In reality, though, the US has severe limits on what it can do in the world, militarily and politically. Most obviously, in the last two decades, the US has lost two significant wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Its efforts to create a secure, stable order in Europe through NATO expansion have either failed or backfired, depending on how charitable you want to be about it. “Efforts to defend everything leave one defending not much of anything,” Barry Posen writes in his 2014 book Restraint. US efforts to impose a regime of democracy and liberal hegemony have been expensive failures, leading to great misery and few positive benefits.

The US is especially constrained when confronting nuclear states. It’s one thing to go bumbling about in Iraq, attempting to change the regime of a state which has little to no ability to seriously threaten the security of the United States. It’s another to involve oneself in a shooting war with a nation that could feasibly render the earth uninhabitable if its authoritarian ruler really feels that his personal safety or power is threatened.

That’s why Biden has, prudently, withdrawn US troops from Ukraine, rather than increasing forces (though he has increased troops in Poland, which Russia is notably not threatening to invade.) An exchange of fire between Russian and US soldiers could escalate to the end of the world pretty quickly. Avoiding that is imperative.

What this means is that the US doesn’t have the power to unilaterally win a war, and also doesn’t have the power to unilaterally prevent war. We can’t unilaterally do anything. Russia decied to invade Ukraine, and there is now a war, even though the US didn’t want one. Impassioned calls for the US to escalate in order to prevent war and impassioned calls for the US to deescalate to prevent war alike missed the core truth that, escalate or deescalate, the US wasn’t the main actor here. The main actor was Russia.

Of course, the US can take steps to try to end the war and pressure or encourage Russia to withdraw. The US has put in place a range of economic sanctions against Russia. The EU has done the same and has also banned Russian planes from European airspace and plans to shut down Russian media outlets operating in EU countries. Germany is sending Ukraine arms. Some politicians, like progressive VT Senator Bernie Sanders, have recommended that along with these sticks, we should try a carrot, and consider promising Russia that there will be no NATO expansion into Ukraine if Russia abandons its warmongering. These all seem like reasonable approaches to ending the war and the invasion.

But it’s also important to remember that reasonable approaches aren’t necessarily going to work. Sometimes, especially in international matters, there isn’t any approach which will work. The US simply doesn’t have the power to impose its will on the globe. Some politicians and pundits, of various political persuasions, may insist on seeing the US as an irresistible, colossal world policeman, dispensing war or peace at whim. But that vision has little to do with a reality in which the US is but one actor in a complicated international situation that includes Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, the EU, the UK, NATO, and numerous other countries and institutions, many of which are more directly involved or better positioned to intervene than the US.

A recognition of US limitations is the best grounds for US de-escalation, worldwide. As Posen argues, there’s little point in having large numbers of troops in Europe and Asia when realistically the cost of nuclear war is too high to risk for anything but a threat to the US much closer to home. Humanitarian democracy-building interventions are high cost for little reward, given our experience in Afghanistan and the Middle East.

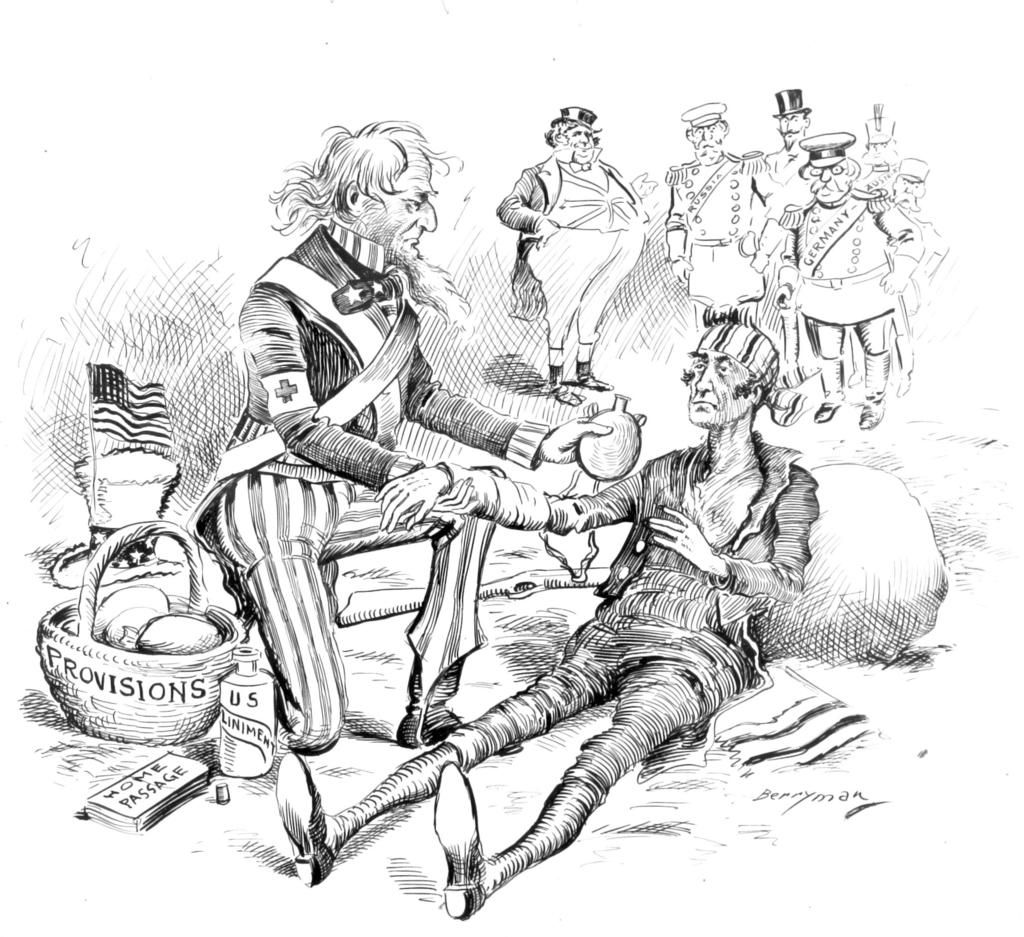

That doesn’t mean the US can’t do anything on the international stage. We could do a lot that would improve the lives of people around the globe and increase our own standing.

Vaccinating the world against Covid—at a cost of roughly $50 billion—would be cheap by defense budget standards, and would do a lot more to protect American people than more fighter planes. Rolling back restrictive immigration and refugee policies would be a huge boon to desperate people and to the reputation of the US. Spending some large portion of that defense budget on combatting global warming would again be a much more significant help to US and global security than anything we’re doing in Ukraine.

All of these are a hard sell compared to increasing military budgets. That’s because military action creates the illusion of power, force, action. Planes and bombs make politicians and the public feel like they’re in a kick-ass movie, fighting evil and taking names. Progressives can get caught up in inverted but similar narratives, heady with the rush of denouncing the all-powerful evil empire.

But the best way to peace has little to do with empowerment or genre thrills. If we want less war, we need to recognize that in a lot of situations, all our bombs and tanks and planes simply aren’t going to make the world do what we want. We’re not the sole arbiter of what happens on earth. If everyone recognized that, we’d have taken a first step towards being a less violent nation.

Featured Image is The End of the War Begins For Humanity’s Sake, by Clifford Berryman