The Democratic Peace as a Spontaneous Order

The importance of liberal democracy as a social system rather than merely as a state.

The fact that representative democracies have never waged war on one another, is probably the most important pattern in the modern world that few have recognized. If the democratic peace is more than a statistical fluke, it solves the most destructive problem in many thousands of years of human history. But if it is not a statistical fluke, why does it exist?

I will argue here that all the most common explanations, ideological, institutional, and realist, are flawed, and the real explanation is the such democracies are spontaneous orders in F. A. Hayek’s terms, and not traditional states.

A spontaneous order as Hayek and Michael Polanyi developed the concept was an emergent ordered pattern within society that arose ‘spontaneously’ from the actions of people pursuing ends of their own choosing. Hayek famously emphasized the market as such an order and Polanyi emphasized science, but both explored similar unplanned patterns of order in society such as language and custom. Hayek and Polanyi were part of post-war social and physical scientists investigating what we today call complex adaptive systems. Both recognized the abstract similarities between science and a free society, but neither pursued it very far (Polanyi 1969, p. 49-72; 1951; Hayek 1979, p, 179-90).

Key definitions

The key terms for grasping this issue are “democracy” and “war.”

In this paper a liberal democracy has freedom of political organization, of the press, formal equality under the law, contested elections with at least two cycles of peaceful transitions of power, and a very broad, ideally universal franchise My argument treats democracies as systems of complex interrelationships shaped by democratic rules. Such networks take time to form. Two peaceful transfers of power seem sufficient for them to arise not only within but also between democracies.

“War” refers to extended conflicts with at least a hundred casualties. War need not be declared for a conflict to be classified here as a war, for example that between Greece and Turkey in 1974. On the other hand, using the word “war” to describe the so-called “Cod Wars” between the UK and Iceland, or the “Pig War” between the US and Great Britain, were not wars as I use the term. The Cod War had one (unintended) fatality, and the “Pig War,” again, only had one: a pig.

Spontaneous order and complex adaptive systems

Today “spontaneous order” is largely applied within the social sciences as a subset of the larger category of “complex adaptive systems” and similar terms that also apply to biology and perhaps elsewhere. In the social sciences similar processes exist in the evolution of language and customs. What these terms share in common is describing how ordered patterns arise independently of the intent of those whose actions generate it. What distinguishes spontaneous orders is the nature of feedback that shapes emerging patterns (diZerega 2024, pp. 117-9).

Spontaneous orders emerge from the basic liberal principle that all people should share equal legal status, and binding relations must be shaped by formal agreement. All people are free to apply common abstract procedural rules to pursue any project of their choosing, and any project is legitimately pursued so long as it is done so within this framework. Consequently, independent equals will inevitably pursue different ends within a common framework, some of which will prove incompatible. Order emerges within such systems guided by feedback signals aiding in pursuing successful plans and avoiding those likely to fail within complex environments whose details they can never grasp. Such feedback is systemically defined and, ideally, independent of deliberate manipulation.

As Hayek emphasized, markets and science are both discovery processes where outcomes reflect the values inherent within the generating rules (1979, p, 179-90). In the market feedback signals are profit or loss defined in monetary terms. In science they are areas of consensus or rejection within a field of study. In democracies it is the ordered political system arising from seeking votes.

Some readers might object that Hayek never called democracy a spontaneous order, and in fact was often critical of it compared with market processes. However, his criticisms focused on democracy in terms of majority rule. But in reality, the majority rarely rules. Something much more complex is happening (Kingdon 1995).

In The Constitution of Liberty, he came very close to the position I am arguing here (Hayek, 1960, pp. 108-109):

We may admit that democracy does not put power in the hands of the wisest or best informed and that at any given moment the decision of the government of the elite may be more beneficial to the whole; but this need not prevent us from still giving democracy the preference. It is in its dynamic, rather than its static, aspects that the value of democracy proves itself… the benefits of democracy will show itself only in the long run, while its more immediate achievements may well be inferior to those of other forms of government

Hayek’s argument here is identical in logic to one he made for the market superiority over planning: the market is “a multi-purpose instrument which at no particular moment may be the one best adapted to the particular circumstances, but which will be the best for the greater variety of circumstances likely to occur” (Hayek, 1976, p. 115; see also Kirzner, 1973, pp. 232-3).

Crucially, both Hayek and Polanyi contrasted spontaneous orders with organizations.

Organizations and spontaneous orders

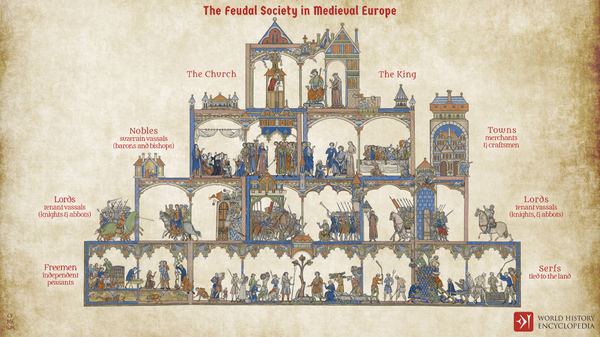

Organizations are groups of people ordered hierarchically to pursue a common goal. We are surrounded by organizations, and are likely personally involved in many. In an organization power is top-down, though the rulers could be an individual or a group. Those under their authority are subordinate to their power. They are valued in terms of their ability to contribute to the organization’s success.

Organizations can be democratic, as in co-operatives and labor unions, but as organizations, the standard for their success is clear cut. A co-op must succeed in the market and a labor union must protect its members’ interests from management with business organizations. Insofar as they are democratic, other goals are subsidiary, if they exist at all. Organizationally, membership is subordinated to these goals. To see the difference between a democratic organization and a democracy, consider a town government. Citizens are not subordinated to any goals, and are free to argue for mutually exclusive ones. They may not be expelled for disloyalty to the current administration, and are free to challenge it in elections they could win. Only during times of major crisis is the democratic process subordinated to something like majority rule. A war, plague, or natural disaster can accomplish this temporarily, Significantly, it is during these times of maximal agreement as to the most important ends that democratic processes are most often suppressed.

Confusions about democracies and states

The term "state" in the modern sense refers to organizations of rule. In The Prince, Niccolo Machiavelli’s term lo stato is usually translated as “state.” In her study of his thought Hanna Pitkin argued asking whether Machiavelli meant the nation or the Prince’s position by the term is misleading. For him, “the two form a single concept” (Pitkin, 1972, p. 312). Around 100 years later, Louis XIV became known for his claim “L’etat c’est moi” or “I am the state.” The state was explicitly equated with the will of a single person. The classic image depicting a state in this sense is Thomas Hobbes’ famous frontispiece to his Leviathan. Today the institutional structure of a state is rarely a Hobbesian autocracy, but rule remains top-down. There might even be elections, as in Putin’s Russia, but their outcome is determined by the ruler.

This distinction’s clarity is obscured because “state” is used in other contexts such as being sovereign, being the source of law, and waging war. In these cases, a democracy is a state. Hayek made a distinction about the term ‘economy’ that clarifies this issue (1976, pp. 107-32). We speak of a ‘market economy’. But we also describe the economy of a business and that the Soviet Union had a ‘planned economy’. ‘Economy’ is used to describe both the market, a spontaneous order; and businesses and the Soviet Union, which are organizations. The same blurring applies to ‘state.’ In terms of sovereignty, making laws, and waging war, a democracy is a state. But in systemic terms, it is a spontaneous order.

The executive and the state

Within democracies the executive function is the equivalent of the state’s organized rule, but it has been subordinated to civil society. In the United States, were the President to control the legislature, as Putin does in Russia, we would shift from being a liberal democracy to being a state.

The apparent exceptions to the democratic peace argument concern cases where the executive has won independence from the legislature. It is then the closest to a traditional state, and acts like one when it is free from legislative oversight. The democratic system requires a subordinate executive.

Even if popular checks and controls on a powerful executive are strong, it is in the realm of international politics that institutionalized checks on the executive power are weakest. Additionally, patriotism and the general sense of standing together in the international arena helps create a relatively uncritical trust and support for the executive, especially in times of crisis. It is in the chief executive's political advantage to be in charge during times of international crisis, so long as s/he can appear to be "in charge" (Lowi, 1985).

It is here that apparent exceptions to the democratic peace contention arise. Executive secrecy enabled American actions against Iran, Guatemala, and Chile, and by any reasonable criterion Chile was a democracy. Neither internal institutional factors nor democratic norms prevented these assaults on democratic governments.

In his analysis of American foreign policy Stephen D. Krasner observed that "Central decision-makers have been able to carry out their own policies over the opposition of private corporations [and other societal interests] providing that policy implementation only required resources that were under the control of the executive branch" (Krasner 1978. 18, 89, my emphasis).

Faulty explanations

Theories seeking to explain the democratic peace generally distinguish between two broad approaches for why there has never been a war between two democracies: normative and institutional. An alternative explanation claims what we call the democratic peace has nothing to do with nations being democracies.

One emphasizes cultural and normative factors. As Bruce Russett puts it, "By this hypothesis, the culture, perceptions, and practices that permit compromise and the peaceful resolution of conflicts . . . within countries come to apply across national boundaries toward other democratic countries" (Russett, 1993, p. 31)

Cultural similarities did not prevent the War of 1812 or the U.S. Civil War and a common commitment to a religion praising peace did not prevent the Thirty Years War. The current war between Russia and Ukraine is happening despite strong cultural similarities.

Ideological similarities are no better. During the Cold War every Communist ruled state whose party had come to power on its own, and bordered another such party, fought a serious border conflict or war with its neighbor save only Albania and Yugoslavia. Russia fought China, China fought Vietnam, and Vietnam fought Kampuchea. Albania worried enough about a Yugoslav invasion to form a protective alliance with Stalin’s Russia to prevent it (Finn 2022).

Religions of peace fare no better. From the beginning of the Sinhalese civil war in 1983 to its end in 2009, Buddhist monks opposed negotiations and cease fire agreements and most supported military solution to the conflict. The head of the Department of Buddhist Philosophy in the Postgraduate Institute of Pali and Buddhist Studies in Colombo, observed "Sinhala Buddhist nationalists are ... opposed to any attempt to solve the ethnic problem by peaceful means; and they call for a ‘holy war’ against Tamils" (Wikipedia 2023). Over and over, throughout human history, similar or even identical cultures, religions and ideologies have proven inadequate to maintain peace.

Internal institutional constraints

Another explanation for the democratic peace is that internal constraints such as the need to ensure popular support, difficulty of planning a surprise attack, and the need for different interests within government to agree, make war between democracies unlikely. But institutional constraints have not prevented democracies from attacking nondemocracies, sometimes in wars of pure aggression, as with America’s invasion of Iraq. The impetus to war there was entirely one-sided. Iraq sought no conflict.

The ‘Realist’ argument

Sebastian Rosato offered a Realist approach as a better explanation for the post WWII peace among democracies in Europe than their internal characteristics, cultural or institutional. Rosato and other realists argue that the international system is a Hobbesian anarchy, and every state is vulnerable to other states and must act accordingly. It was American hegemonic power within the Western alliance that kept the peace (Rosato 2003, pp. 599-600).

John Mearsheimer, perhaps the principle contemporary realist, predicted the end of the Cold War and US domination in Western Europe, would see a rebirth of the international anarchy that long plagued Europe (Mearsheimer 1990)

If you believe (as the Realist school of international-relations theory, to which I [Rosato has co-authored papers with him] belong, believes) that the prospects for international peace are not markedly influenced by the domestic political character of states--that it is the character of the state system, not the character of the individual units composing it, that drives states toward war--then it is difficult to share in the widespread elation of the moment about the future of Europe.

In 1990 Mearsheimer predicted

The next forty-five years in Europe are not likely to be so violent as the forty-five years before the Cold War, but they are likely to be substantially more violent than the past forty-five years.

In an additional criticism of the democratic peace argument, Rosato also claimed ‘democracies’ did fight one another in the past, and provided a list to prove his point. But Rosato’s claim rests on a more minimal definition of democracy than the one we propose to analyze here.

These practices of broad and universal suffrage, a free press, competitive elections, and at least two peaceful transfers of power develop an internal system of political peace. Structural and institutional issues do play a role in the democratic peace, but the reason is the systemic context within which they exist. When democracies interact with one another these systemic characteristic spill over into their international relationships. It is the embracing international system arising between democracies that keeps the peace, not actors and not specific institutions.

As spontaneous orders, democracies are far more than just elections, for they require the entire society to be engaged in various ways leading to the final choice (Kingdon 1995). The same holds for markets and science, by the way.

What about the ‘realist’ alternative? US dominance of other democracies in a bipolar world imposed order cannot account for the war between Greece and Turkey in 1974. The military junta overthrew Greek democracy, and then attacked Cyprus, precipitating a military response by Turkey. Thousands died. Both were NATO members, although Greece then left its military wing, rejoining in 1980. That the US was the dominant power made little difference. That the junta was a military dictatorship made a great deal.

Nearly 35 years have passed since Mearsheimer’s 1990 article, and there has been no weakening of peaceful relations between democratic European nations. Quite the opposite. There has been continued blurring of national boundaries throughout the EU. Britain joined, then left, peacefully. Many Britons, perhaps a majority, want to rejoin. This is not what Mearsheimer's theory predicted. Indeed, his predictions are now supported only by the actions of undemocratic regimes such as Russia and, now, Hungary (Reuters, 2024). The democratic peace hypothesis fits actual events and the realists’ alternative does not.

Democratic transformations

We can return now to the question of whether norms or structures are most important in explaining the democratic peace. They cannot be separated. Systems are networks of interconnected relationships. The rules which generate a democratic polity embody specific liberal normative principles, including tolerance of differences, equality under the law, and unwillingness to resort to force. They generate complex social connections that operate independently of particular intentions. Crucially, boundaries become more porous. We can expect norms and institutions to mutually strengthen one another over time.

The internal society of a democracy will be progressively transformed by that system. The causes of the democratic peace, then, have to do with the fundamentally different systemic character of democratic polities growing out of the mutual interaction of norms and institutions. War is not rooted in ‘human nature.’ It emerges from specific systemic contexts, as peace reflects others (diZerega 2015). War, as Randolph Bourne wrote, “is the health of the state” (Bourne 1918). But representative democracies are not states. They have incorporated the executive functions that characterize states into a radically different framework, subordinating it to civil society.

Liberal democracy is the first institutional form to solve one of humanity’s greatest curses: the horrors of war. It does so not because liberal democracies elect better people, but because the people elected must operate within a spontaneous order and not an organization. No one deliberately intended this extraordinary outcome. The democratic peace is an invisible hand phenomenon, which may be why so many ignore its significance.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

diZerega, Gus. 2024. Review of Toward a Hayekian Theory of Social Change. P. Boettke, E. Dekker and C. Van Schoelandt, eds. Cosmos and Taxis. 12: 56. 2024. 115-28. https://cosmosandtaxis.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/review_dizerega_ct_vol12_iss5_6.pdf

_____. 2015. Not Simply Construction: Exploring the Darker Side of Taxis. Cosmos and Taxis, vol. 3, no. 1, 2015. https://cosmosandtaxis.files.wordpress.com/2015/11/dizerega.pdf

Bourne, Randolph. 1918. War is the Health of the State. Libcom.org. 2007. https://libcom.org/article/war-health-state-randolph-bourne

Finn, Daniel. 2022. Albania’s History of Communism and Postcommunism Has a Message for Our Time. Jacobin. July, 2022. https://jacobin.com/2022/07/albania-history-communism-postcommunism-hoxha-liberalism/

Hayek. 1960. The Constitution of Liberty. Chicago: Henry Regnery and Co.

_____. 1976. Law, Legislation and Liberty, Vol. 2: The Mirage of Social Justice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

____. 1979. Law, Legislation and Liberty, Vol. 3: The Political Order of a Free People. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kingdon, John. 1995. Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies. 2nd. Ed., New York: Longman.

Kirzner, Israel. 1973. Competition and Entrepreneurship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lowi, Theodore. 1985. The Personal President. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Mearsheimer, John. 1990. Why We Will Soon Miss The Cold War. The Atlantic Monthly, August 1990. Volume 266, No. 2. 35-50.

Pitkin, Hanna. 1972. Wittgenstein and Justice. Berkeley: University of California.

Polanyi, Michael. 1962. The Republic of Science: Its Political and Economic Theory. Ed. Marjorie Grene. Knowing and Being: Essays by Michael Polanyi. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969. pp. 49-72.

____. 1951. The Logic of Liberty. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Reuters. 2024. Hungarian far-right would lay claim to neighboring region if Ukraine loses war, Jan.28, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/hungary-far-right-would-lay-claim-neighbouring-region-if-ukraine-loses-war-2024-01-28/

Rosato, Sebastian. 2003. The Flawed Logic of Democratic Peace Theory, American Political Science Review Vol. 97, No. 4 November 2003.

Russett, Bruce, 1993. Grasping the Democratic Peace: Principles for a Post-Cold War World, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Wikipedia. 2023. Buddhism and Violence. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buddhism_and_violence

Featured image is One World Trade Center, by Michael Vadon