The Fruit of the World's Trial and Error: Importing COVID-19 Containment Tactics

The good news is that some countries are winning the war with COVID-19; fruit from the vast trial and error occurring around the globe, as numerous nations wrestle with the same problems with varying degrees of severity. The bad news is that, at the moment, nationalist and provincial reactions to the crisis predominate, and there does not therefore seem to be many seriously attempting to learn from these successes.

Below, I examine specific lessons we can learn from other countries in the struggle to take back our lives from COVID-19.

Contact tracing

The vast scale of the US outbreak means that manual contact tracing just won’t be enough. Digital contact tracing can provide better capacity, but it comes with challenges in terms of privacy and compliance with US privacy law.

Mobile apps have been developed for people to track instances of COVID-19 exposure. When a person installs these apps on their phones, the app uses either Bluetooth or GPS to record when two or more users have been in close proximity of themselves for a long period of time, long enough for the virus to be transmitted.

And when a user reports that he or she is COVID-19 positive, the app instantly alerts others who were close enough to the infected user, and advises them to go for a test. In the US, the sim tracking falls into a rather strange category in which it is often governed by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

HIPAA barriers to implementation

On February 3, 2020, HHS issued a bulletin: HIPAA and the Novel Coronavirus. That bulletin details the flexible approach of the HIPAA Privacy Rule in setting the parameters for the authorized use and disclosure of protected health information (PHI) in situations like the current pandemic. While the bulletin did focus on the authorized uses and disclosures, it was overly restrictive and it ultimately failed to envision the current pandemic.

The spread of coronavirus in the United States has raised questions about HIPAA compliance and enforcement. Initially, the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) declined to relax the requirements of the HIPAA Privacy Rule.

The Iowa Freedom of Information Council argues that the HIPAA law is being used too broadly as a reason to not release data on the spread of COVID-19. Journalists have been denied requests for data on the number of COVID-19 tests performed or hospitalization rates, according to local ABC affiliate KCRG. Health officials point to HIPAA as the reason they cannot disclose this data.

And on March 16, HHS responded to the COVID-19 pandemic by relaxing some of the enforcement of certain provisions of the HIPAA Privacy Rule in its COVID-19 & HIPAA Bulletin: Limited Waiver of HIPAA Sanctions and Penalties During a Nationwide Public Health Emergency. The limited waiver applies to hospitals that have instituted a disaster protocol and waives sanctions and penalties for noncompliance with several provisions of the HIPAA Privacy Rule.

Under the relaxed HIPAA regulations, hospitals don’t need to obtain a patient’s agreement to speak with family members or friends involved in the patient’s care. Additionally, hospitals do not need to comply with the requirement to honor a request to opt out of the facility directory. However, those waivers are limited. Future developments in the COVID-19 pandemic could trigger more waivers that could ease or complicate HIPAA’s overly restrictive approach.

It is important for the public to recognize what trade-offs would be involved in overriding HIPAA, were that option available. The digital contact tracing apps used in other countries require users to willingly share their private health information with a third party. A key challenge that digital contact tracing faces in the US is that the organisations that must be involved to make it work, such as Apple and Google, do not belong to the covered entities under HIPAA. They do not meet the standards of data protection required for processing health information under that 1996 law.

Apple and Google are attempting to address privacy concerns by limiting the information collected and anonymizing what is pulled in so that such personalized tracking isn’t possible. Both Apple and Google also stated that apps built to their specifications will work across most iPhones and Android devices, eliminating compatibility problems. They have also forbidden governments to make their apps compulsory and are building in privacy protections to keep stored data out of government and corporate hands and ease concerns about surveillance.

The battle is not between data protection and public health. It is not a zero-sum game. Health data is crucial for scientific research aimed at developing treatment options and vaccines. Contact tracing is vital for curtailing the spread. The purpose of data protection is to protect people (personal data) and prevent abuse.

Any kind of implementation of the tracing app that violates the HIPAA laws could result in an OCR audit, alongside a penalty. This can range from $100 to $50,000 per violation. A temporary exception to or permanent update of HIPAA will have to be created in the US to fight this pandemic effectively.

Countries using contact tracing and their success

A considerable number of countries have implemented the digital contact tracing strategy and they’ve been making impressive progress so far. South Korea has implemented aggressive contact-tracing apps to track a person’s detailed whereabouts. China also launched an app that allows people to check whether they have been at risk of catching the coronavirus. Singapore’s TraceTogether was an early pioneer and reeked a high number of users after it was released. Other countries such as Australia and Germany have worked impressively to implement these apps. Germany being under the GDPR, one of the most robust data protection laws in the world. Yet they are still able to pull this off.

For virtually all countries, including the United States, the use of any contact tracing app is voluntary. However, for the contact tracing to become very effective, literally half of the country’s entire population must be users. We are talking about a significant amount of data that will include user location and their personal health information.

If deployed properly, contract tracing apps by employers, combined with other measures, could be an effective way for employees to return to the workforce. However, before these apps are deployed, employers should take caution to vet the technologies that are being used in order to ensure that employee privacy is respected. And the law will need to be changed, or a temporary exception created.

Extensive and quick testing

More than 65 million COVID-19 tests have been done in the US. It’s an impressive figure, nearly doubling the number of any other country. But while the US has performed the highest total number of tests worldwide, it does not have the highest rate of testing per capita.

When it comes to tests performed per number of residents, the US lags behind the UK, Israel, and Russia. The UK has performed more than 270,000 tests per 1 million residents, while Israel and Russia have performed over 214,000 and 212,000 tests per million people, respectively.

Conversely, the coronavirus testing center at Berlin’s Tegel Airport, Germany, is now testing anyone returning from a “hot zone” on entry for free. Ms. Kirstein, a returnee from Serbia, was on her way in a matter of minutes after having her nose and throat swabbed. She expected an answer in 24 to 48 hours. “The test was not only swift, I think it is super. It was so easy to find, and best of all, it didn’t cost me a thing.” She said.

Whereas such tests can be hard to find in the United States, with unpredictable costs.

In mid-May, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced that it had authorised the use of the very first rapid diagnostic test that could detect COVID-19 in as little as 45 minutes.

The FDA also stated that the new testing can be handheld completely at home—if companies don’t find the rules too burdensome. A routine screening of people who don’t even know they have COVID-19 could transform the fight against the pandemic.

According to the FDA Commissioner Dr. Stephen Hahn, “These types of tests will be a game-changer in our fight against COVID-19 and will be crucial as the nation looks toward reopening.”

But so far, the FDA is not allowing anyone to actually sell these tests for at-home use. Nevertheless, several testing experts, including Dan Larremore of the University of Colorado, said that the FDA’s move is a step in the right direction, and it could encourage companies to pursue inexpensive, rapid, at-home tests.

But Dr. Michael Mina, an infectious disease epidemiologist at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, said the way the FDA’s guidance template is written makes it less likely that such crucial tests will reach the general public.

The template shows off how a sample is to be collected, analysed, and how results are to be shown to a user without having to send a sample to the lab for analysis. The template also outlines how accurate tests must be, without slightly lower standards than the lab-based tests.

“The (required) software alone will pose an incredibly large hurdle for many,” Mina said via email. “Unfortunately the template does not offer this type of ‘new’ avenue that I think is going to be necessary if we want to see truly $1 daily tests become a reality.”

Mina said the standards should be lowered further. People are contagious only when there’s an extremely high virus level in their body, which can be detected by a less sensitive test. An infection that goes undetected by a less-sensitive test would be caught a few days later when the person is tested again, he said. Or the person would already be on the way to recovery and probably wouldn’t be contagious.

Public health specialists have stressed that the current testing delays render the tests essentially worthless because it takes so long to get results, and that by the time people find out they have the virus, they may have already passed it along to others. Other tests are fast, but they are very expensive, and it’s unlikely that they’ll be regularly used. A clinic in Massachusetts, for instance, charges $160 for a rapid test that is not covered by insurance.

In another approach, Intrivo Diagnostics of Santa Monica, California, and Access Bio of Somerset, New Jersey, are collaborating to design and distribute a rapid at-home test.

Dr. Michael Harbour, chief medical officer of Intrivo, said he expects to complete the FDA approval process by the end of October. Their test provides a finger-pricking device and analyzes a drop of blood. A blue line would indicate a positive for the virus; no line would be an all-clear. He would not comment on the per-test cost, however, and it remains to be seen if it will sail through the FDA process as quickly as he anticipates.The FDA, Harbour said, has “moved the goalposts” several times, requiring testing companies to follow one protocol and then another.

Quest Diagnostics announced on Wednesday that the FDA issued emergency authorisation to use a new technique that will cut testing to two to three days for some people. Testing laboratories such as Quest Diagnostics and LabCorp have struggled to keep up with testing as cases skyrocket in the west and south of America.

With the new FDA testing technique, the company expects to be able to perform 150,000 tests per day by next week and 185,000 per day by Labor Day.

How other countries have dealt with re-opening.

As school officials in the United States debate on when it will be safest to reopen schools, looking abroad might provide some insights. Nearly all the countries in the world left their schools shuttered in the early stages of COVID-19. Many of these countries have since sent students back to class with a rather varying degree of success.

For Israel, it was too much, too soon. Israel took stringent steps in the early stages of the pandemic. They severely restricted everyone’s movement and closed all schools. By June, they were being lauded globally for containing the spread of COVID-19.

But not long after schools reopened in May, on a staggered schedule paired with social distancing and mask mandates rules, COVID-19 cases surged across Israel. Schoolchildren and teachers were getting sick. Today, several hundred Israeli schools have closed again.

Many went as far as blaming lax enforcement of health guidelines in schools. The weather was of no help. And in May, a record hit wave hit Israel, making masks uncomfortable for the students to wear.

But schools were only part of a broader reopening in Israel that, many experts claim, came too soon and without sufficient testing capacity. Israel’s public health director, Siegal Sadetski, resigned in early July, saying the health ministry had ignored her warnings about reopening schools and businesses so rapidly.

In Sweden, it was more of a hands off approach, really. They never shut down schools in Sweden. Some call it part of the Scandinavian country’s risky gamble on skipping the COVID-19 lockdown. Only students of age 16 and above stayed home and learned remotely. Social distancing and wearing a mask was recommended, but optional, in correspondence with the Swedish government’s emphasis on personal choice.

This strategy went as far as to earn praise from President Donald Trump but some resistance from Swedish parents, especially those whose children have health issues. The government threatened to punish parents who didn’t send their kids to school. Sweden’s plan seems to have been safe enough. Restaurants, schools, and Business owners go about with their daily routines.

Yet more than 5,700 people have died with Covid-19 in Sweden, a country of just 10 million. It is one of the highest death rates relative to population size in Europe, and by far the worst among the Nordic nations. In the short term, Sweden’s Covid strategy is affecting its usually close relationship with its neighbours.

Norway, Denmark and Finland opened their borders to one another in June, but excluded Sweden due to its high infection rate, although Swedes from less affected regions have since been given more freedom to visit Denmark.

A bigger problem could be the impact on Sweden’s wider international reputation for high-quality state health and elderly care, “There has been a blow to the Swedish image of being this humanitarian superpower in the world. Our halo has been knocked down, and we have a lot to prove now.” Says Helen Lindberg, a senior lecturer in government at Uppsala University

Only one young Swedish child is believed to have died of coronavirus. A true example that whereas the nation’s strategic approach was not as good as they hoped, the approach for reopening of schools proved a significant success.

In Denmark, the decision of when and how to reopen schools was made by the central government together with the Parliament. This allowed for municipal councils (similar to school districts in the US) to develop their own plans, and school leaders and teachers to do the same for each individual school based on guidelines from the National Board of Health.

Finland had a similar decision-making process. Minister of Education Li Andersson tweeted that to extend the school closures, the government would have to prove that opening schools would be unavoidable in the current situation and was “a matter of weighing basic rights.”

In Denmark and Finland, the decision to gradually reopen included staggering by age, with schools for the youngest children reopening first. The main factor underlying the decision was the emerging evidence indicating that children play a small role in spreading the virus.

It has been so far so good for Japan. They had mostly made efforts to keep the virus under control. But later took a conservative approach to reopening schools in June.

Several schools have their Different strategies, but Japanese students generally attend class in person on alternating days, so that classrooms will be only half full. Lunches are silent and socially distanced. The students also undergo daily temperature checks.

These precautions are more stringent than those in many other countries. Still, some Japanese school children have gotten COVID-19, particularly in major cities. Parents, students and teachers continue to express hesitancy about returning to school and displeasure over reopening measures

Schools in Germany continue to follow new directives for reopening schools: Hallways are now one-way avenues, masks must be worn in classrooms, seats are assigned and spaced far apart, and everyone is encouraged to wear heavier clothing as windows must be kept open to improve air circulation. All of that is in addition to already common practices such as keeping a 6-foot distance between students when standing in line.

But implementing these measures has come with challenges. For example, some schools simply can’t fit every student inside the building if they are to maintain social distancing. In the Neustrelitz high school, only about a third of the student body can be in class at a time — and even then, a teacher might have to teach two groups in two classrooms at once.

New Zealand’s government recognizes that not everyone is ready to return to school. And they have offered a pathway to allow parents the liberty of sending their kids back to school only when they feel comfortable to do so.

New Zealand’s students went back to class on May 14, but students and parents who thought that date was too soon were allowed to opt for a “transition arrangement” with their school.

“We also know that children and young people’s wellbeing is important and there may be students whose parents are anxious about their return to school, as indeed the students themselves may be. In these instances, we can help you work through a transition arrangement that will take longer than the period of time talked about here,” New Zealand’s Ministry of Education stated this month.

However, the government provided no real clarity on what such an arrangement would look like or for how long it should last. Those details were left up to the schools, all but assuring a lack of uniformity in the kind of “arrangements” agreed to throughout the country.

After shutting down in March, schools in Italy are to reopen on September 14th, the government has announced, with “at least a billion euros” in funding to implement new safety measures.

The €1 billion in funding is intended to cover, among other things, the employment of 50,000 extra teachers and temporary school staff. However, this is a critical step and is seldom discussed in the US Safe reopening would require much larger staffs, and therefore budgets.

The education minister Azzolina said, “We are giving clear but flexible solutions. For safety you need space, we can’t go back to chicken coop classes. Schools have never seen this much money.“ Adding that teachers would receive a bonus in July of between €80 and €100, in what she described as a “recognition they deserve, because the salaries of Italian teachers are among the lowest in all of Europe.”

On Thursday last week, ahead of the meeting between the minister of Education, Lucia Azzolina, and the representatives of the Regions, Provinces and Municipal administrations, in 60 Italian cities rallies were organized to protest against the plan.

The protesters point out a number of flaws in the plan. Generally, the plan is considered to place too much responsibility in the hands of schoolmasters and local administrations, which are going to have to rethink the entire organization and offer in a substantive way, without having clear directions.

Furthermore, the practice of distance teaching, which was not homogeneously efficacious around the country during the lockdown, with varying levels of implementation and success between different schools and regions, is also regarded as a poor substitute for traditional school, destined to aggravate inequalities between students.

“If the plan that the Ministry is drafting is going to lead to a classist school system, where inequalities will rise and where only those who can afford private lessons will make it, we will continue fighting”, said Costanza Margiotta, leader of the committee. Protesters are asking for a deep revision of the plan and to have certainties over the school start in September, which needs to be “safe, allowing everyone’s presence and work without interruptions”.

The gradual reopening of schools after the crisis provides an unparalleled opportunity to rethink the day-to-day experiences of students and teachers. A major cause of Sweden’s strategic failure was because its citizens did not abide by social distancing rules, which the US needs to take note on. New Zealand’s decision to offer an individual choice to parents on whether they want their kids to return to school or not is worth learning from as well.

In much of the world, schools that closed in March remained closed through the summer break, and autumn will see a wave of reopenings. For millions of especially vulnerable children, however, the break may continue indefinitely. Many low-income countries lack the resources to shrink class sizes or provide everyone with masks and so are hesitant to reopen in the midst of a pandemic.

In June, Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina said schools will likely stay shut until the danger of COVID-19 has passed. Similarly, officials in the Philippines said in-person schooling will not resume until there is a vaccine to protect against COVID-19.

In other places, ranging from Mexico to Afghanistan to the United States, planning for fall 2020 is underway. In the United States, school districts are releasing a patchwork of plans, which often include hybrid models that alternate distance learning with small in-person classes.

Whether those plans sufficiently protect children, staff, and communities from COVID-19 will depend on how case numbers look as opening day approaches. This reality was thrown into stark relief late last month, when Arizona’s governor announced he would delay the state’s school reopening by at least 2 weeks, to 17 August, because of a surge in cases.

There is no perfect way to reopen schools during a pandemic. Even when a country has COVID-19 under control, there’s no guarantee that schools can reopen safely until there is a vaccine for the virus.

But the policies and practices of countries that have had some initial success with schools point in the same direction. It helps to slowly stage the reopening. Strict mask wearing and social distancing is critical, both in schools and surrounding communities.

And both officials and families need reliable and up-to-date data so that they can continually assess outbreaks – and change course quickly if necessary.

Most countries have national education systems. In the US, school officials in all 50 states must sort through the same politicized messaging and confusing data as everyone else to make their own decisions about whether, when and how to welcome back students.

What lies ahead

Despite all of the commendable methods and strategies of curtailing the COVID-19 pandemic that the US and other countries have been trying, with some variations of success, the only certain solution to ending the virus is for a reliable vaccine to be made. We should all prepare for a 2-3 year period of coping with this problem, and ultimately should be willing to learn from the successes and failures of the vast process of trial and error occurring around the world alongside us.

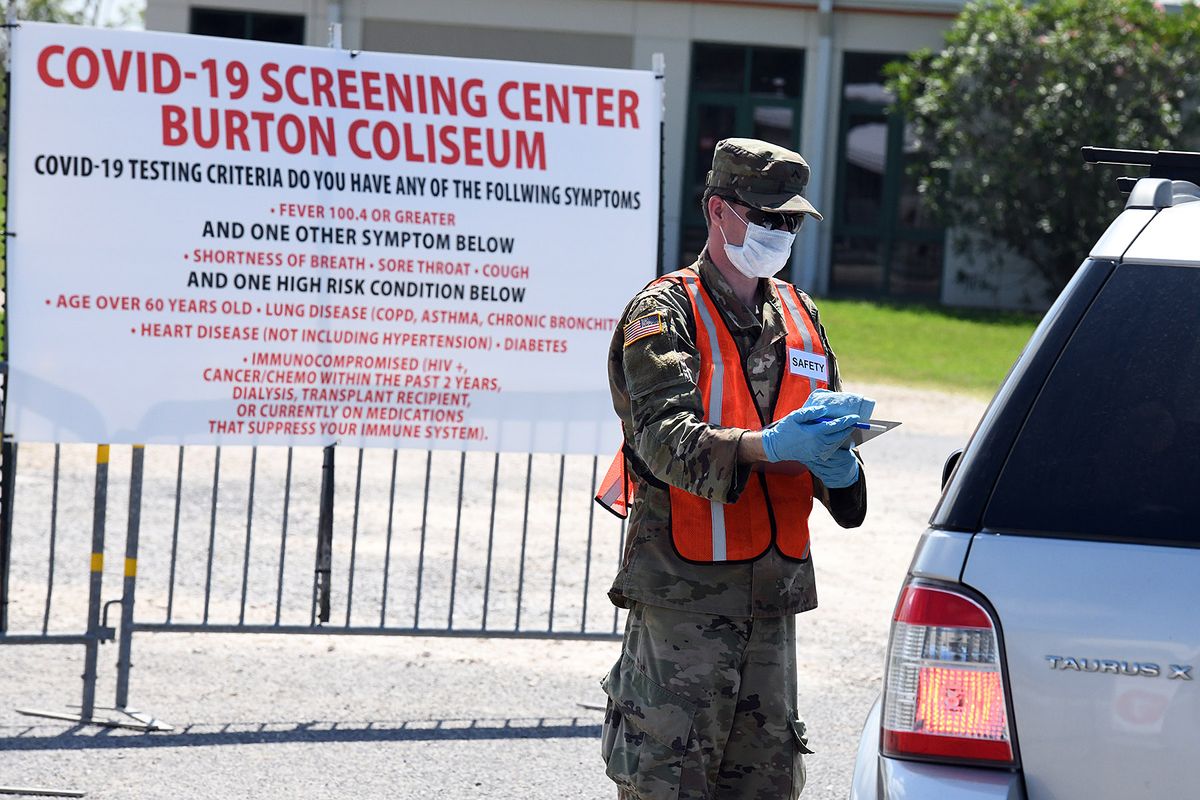

Featured image is the Louisiana National Guard assisting with COVID-19 testing