The Necessary Logic of American Politics: Ezra Klein's Why We're Polarized

Donald Trump’s victory in 2016 came as a shock to most political analysts, and spurred numerous analyses looking to explain the outcome. One insightful explanation comes from Ezra Klein’s book Why We’re Polarized. Klein sees the election as a culmination of our social psychology mixing with a media landscape designed to outrage, in a political system that incentivizes Republicans to become more extreme. We are hard-wired to protect our identities from external threats, and contemporary political parties have become strong proxies for the groups to which we belong. The media and politicians tap into our psychology that makes us react more strongly to threats and antagonism than to positivity. And the American political system was designed centuries ago to represent geography more than popularity in a way that makes Republican electoral success tied more to extreme stances than winning over swing voters. All of this, according to Klein, leads to “a legitimacy crisis that could threaten the very foundation of our political system.” The book’s claim that political parties now stand in for identities, in a way that leads to more polarization than was common in the 20th century, is convincing. However, Klein leaves important social factors unanalyzed, and there is reason to believe he is presenting current trends as more inevitable than they in fact are.

Listeners of Ezra Klein’s podcast will have noticed his focus has shifted away from technocratic policy discussions and towards broader philosophical questions. He has become more interested in talking about veganism or identity politics than the latest NBER paper on healthcare policy. Why We’re Polarized hits somewhere in the middle, using social science research to explain the circumstances that made America so polarized and led to a Donald Trump Presidency.

Klein’s narrative centers on the issue of identities, and the way shifting identities have impacted the current political climate. He draws on both social science and the history of partisanship in the United States to explain the current situation. Historically, a key part of his argument is that the current situation represents a break from mid-20th century norms.

History and social psychology

Most identities used to be weak predictors of one’s political party preference: In 1952, other than southerners and Protestants , no demographic had “more than a 10-percentage point difference in the percentage of its members represented within each party.” Moreover, ideology wasn’t much of a common thread within parties: In 1976, only 54% of Americans thought the Republican Party of Gerald Ford was more conservative than the Democratic Party of Jimmy Carter. When Roe v Wade was decided in 1973, opinions on abortion were essentially split within each party. Polls showed opposition to the Vietnam War was similar between the parties as well.

With parties not firmly defining policy preferences, voters oscillated between elections and split the ticket within races. Between 1972 and 1984, the average difference between how a state voted in one Presidential election and the next was 7.7 percentage points. But as the parties became firmer in the policies they supported, this number became 1.9 between 2000 and 2012. The correlation between parties of a district’s House representation and Presidential candidate went from 0.52 in 1972 to 0.97 in 2018.

In a chapter titled “Your Brain on Groups,” Klein dives into social psychology and political science research suggesting the key to understanding this shift is the way intergroup opposition shapes group decision making. Evidence suggests that our emotions are more heightened during moments of opposition rather than support. Even in the absence of objective differences, experiments show that people will establish arbitrary distinctions among themselves, quickly defining an “us” and “them” that impacts their treatments of each other. Opposition to the “other” is so strong in experiments that subjects “preferred to give their group less so long as it meant the gap between what they got and what the out-group got was bigger.”

Jerry Seinfeld was noting this phenomenon when he observed that sports fans have deep emotional attachments to what boils down to the color of the clothes their team wears. The players change teams, the teams change cities, and the most consistent thing is the uniform. Klein draws parallels between sports fanaticism and political partisanship – deep emotional attachments to our tribe winning, rather than diligent commitment to democratic discourse. In The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Adam Smith remarked on the strong human desire to share in the sentiments of our peers but, notably, we care much more about our friends sharing feelings about our dislikes than our likes. Unsurprisingly, the easiest common ground to find with coworkers is complaining about a boss, or with friends is to gossip about a familiar person. This was brought to bear in the 2016 campaign – Trump’s campaign was much clearer about his opposition to The Swamp than what he stood for.

These dynamics are more or less hardwired into our social interaction. But we’ve become increasingly polarized as these in-group/out-group dynamics have reached a fever pitch in the political realm as various identities have become more aligned with one another into what Klein calls ‘mega-identities’. Our personal identities are a mix of characteristics like where we grew up, our gender, whether we eat meat, our religion, our musical tastes, or whether we own guns. Increasingly, these individual identities coincide more often than they do not. The people who are likely to do yoga in their free time are also likely to live in big cities, drive a Prius, watch MSNBC, and consider themselves non-religious.

Because of this, it is easier for individuals to perceive the political party they support as embodying their values, preferences, and in-groups. ‘Democrat’ or ‘Republican’ become simplified labels for an entire identity. These can be seen geographically and politically – Democrats today represent 78% of districts that have a Whole Foods, and Republicans represent 73% of districts that have a Cracker Barrel.

Klein notes that politics is no longer just an opinion on how to govern, it has become “a means of self-expression and group identity.” With all of our identities now so closely mapping onto a political party, it’s easy to see why any chance of that party losing feels like a threat to our entire personal identity, as if our way of life is under attack. He remarks that “elections feel like they decide whether our country belongs to us and whether we belong in it.”

Klein discusses a mid-20th century aberration in American politics that had much less party polarization. This period was defined by the clear us-versus-them political conflict of the Cold War. Americans then had a common enemy that they do not have today. The September 11th attacks provided national unity briefly, but those effects have petered out. With no common enemy abroad, are we left with no choice but to turn on each other? Polarization may be, as Tyler Cowen recently put to Klein, “the opiate of the masses.” While this does not discount Klein’s analysis, it does suggest our contemporary polarization is not inevitable. If a new enemy emerges, could we break out of our domestic polarization?

Klein is correct that the parties have become more of a proxy for our collective identities, but there are reasons to think this part of Klein’s story is oversimplified. Our lives are fundamentally different in ways that excite the sensibilities he mentions, though they are absent from his analysis. America has undergone rapid secularization in the span of a generation. This removed the community, support system, and shared purpose that religion gave people while leaving a void currently unfilled.

In 2004, the modal American male reported having zero close confidants, compared to three in 1985. The increase of “deaths of despair” coincides with evidence that something is missing from American life. As we have lost previous sources of community, people have found appeal in a cheap, easy alternative: Tribalism. Our strong sensibilities to find common enemies aren’t merely because of an overlapping political mega-identity. There’s a good chance they’re being amplified because we’re lonely. A deeper investigation of this issue would likely improve our understanding of this polarization.

Regardless of its etiology, the problem is not that polarization is inherently bad. People disagreeing is healthy in a democracy. The problem is that the American system is poorly designed to account for this new norm in a way that poses a severe threat to the system’s legitimacy. Politically liberal voters are congregating heavily in urban metropolitan areas. By 2040, 70% of the population is estimated to live in 15 states but be represented by only 30 Senators. One paper estimates that, because of the electoral college, a Democratic Presidential candidate narrowly winning the popular vote could lose the Presidency 65% of the time.

Donald Trump became the Republican nominee for President by winning the most votes from primary voters, a small slice of Republican voters overall. Outside of certain tax cuts and nominating federal judges with conservative legal philosophies, it’s difficult even now to find policies Trump shares with the Republican Party of 2012. But he excited an increasingly white and older base of voters who felt demographic change was threatening their way of life. He said they didn’t have to apologize for being uncomfortable with gender-neutral bathrooms, campus “political correctness,” or having to press 1 for English on the phone.

Once Trump became the nominee, the mega-identity Klein establishes kicks into gear. Team Red has their candidate. Voters say they may not like how he tweets, how he treats women, or calls people names. But opposition to Hillary is much stronger – the person who called half of us deplorables and probably drinks Fair Trade lattes. Trump’s the alpha guy who doesn’t look down at gun ownership or Christian values. How is his strong support within the Republican Party today consistent with his policies that are in stark contrast to Paul Ryan and Mitt Romney in 2012? The explanation, according to Klein, is that “conservatism isn’t, for most people, an ideology. It’s a group identity.” He adds that while policy expertise is not very common, “all of us are experts in our own identities.”

This in turn calls into question the sustainability of the current order. Democrats have won the popular vote in 6 of the last 7 Presidential elections, yet it is they who somehow are struggling to find a winning political recipe. In 2018, Democrats received more than 10 million more votes in Senate elections but still lost two seats. As the popular will becomes less represented by elected officials, the legitimacy of the system becomes harder to defend.

Trump’s tenure in office has also shown the strength of these identities, and the threat they pose to constitutional governance. The recent impeachment hearings demonstrate that no matter what a President does it’s nearly impossible to get enough Senators on board for removal. Despite having a term with constant scandals, Trump’s approval rating has stayed in a narrow band for more than three years. Even with all his offensive campaign rhetoric, Trump received essentially the same share of female and Hispanic voters as Mitt Romney in 2012 and John McCain in 2008. No matter what, his base will support him, and his critics will oppose him.

An overdetermined conclusion

There’s an inevitability underlying Klein’s analysis, that we’re on an alarming path leading to catastrophe absent significant reforms. Klein emphasizes that he is looking at the systemic level rather than just bad actors. Get rid of Donald Trump or Mitch McConnell and the system is still there. Our social psychology still remains the same, liberal voters in urban metropolitan areas will still have the same preferences, and the Senate will still have two representatives from each state regardless of their respective populations.

Klein also asserts that the Republican party is on a path to become more extreme in a way that Democrats are not. Republicans can win the White House or Congress through this geographic setup by appealing to a smaller and relatively homogenous base. The party has since 2004 shifted its effort away from persuading undecided “swing” voters and towards motivating its base. Indeed, research shows that the party voting behavior of self-described independent voters is easier to predict than the partisans of the mid-20th century. This means the party pulls more to the right, which is further away from the median American voter.

Meanwhile, according to Klein, Democrats have to appeal to a large and diverse coalition in a way Republicans do not. They have to win over organized labor, big city business interests, religious minorities, and Silicon Valley yuppies. This causes them to moderate and even provide some appeal to those right of center in order to have a shot at governing. Despite the media focus on very progressive Representatives like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez or Ilhan Omar, the Democratic pickups in the 2018 election were from moderates in red districts.

But just as these forces came together perfectly for Donald Trump to become President, it’s possible that some of them are variables rather than constants. Our social psychology that makes us defensive of our tribes need not be directed at each other, nor does our desire for belonging need to be so motivated by antagonistic forces. Republicans have found electoral success since 2016 at the Federal level with an extreme demagogue at the helm, but the success of moderate Republicans at the state level shows the party is not necessarily going to continue on the extreme path Klein predicts.

Klein clearly spells out how this environment of strict partisanship cripples the accountability mechanism of democracy. But it’s unclear whether his framework necessarily will lead to a more extreme Republican Party and a more moderate Democratic Party. As this is written, Bernie Sanders is the frontrunner for the Democratic Presidential nomination. Whatever else one may say about Sanders, neither his supporters nor his detractors would call him moderate. If the Democrats’ coalition is as diverse and moderating as Klein suggests, how did Sanders become the favorite for the nomination? Could Trump opposition mobilize enough people to support a self-described democratic socialist in the general election? Or will the Democratic voting bloc assert more independence than Republicans of 2016?

The book also fails to fully explain what we are to make of the fact that four of the five most popular governors in America are Republicans in blue states. To Klein, it shows that a different brand of Republicanism canwin. But if moderate Republicans can not only win in blue states but also be popular while governing, how does this square with his beliefs that: 1) political brands have become incredibly nationalized; 2) Republicans have to become more extreme to win; 3) people see any hint of the opposing party as a threat to their identities? The approval ratings of these governors give striking evidence against the inevitability of Republican extremism.

As far as improving the system and dampening the impacts of political polarization, Klein admits he’s writing more to describe than to prescribe. His suggestions range from abolishing the electoral college, granting statehood to DC and Puerto Rico, ranked-choice voting, and ending gerrymandering. He also encourages people to be more involved in local and state politics – the place where individual citizens can actually make a difference.

Klein’s story of how strong our identities are tied to our political behavior is a convincing lens through which to view American politics. And yet his recollection of American political history is a good reminder that not everything is fixed in place. The policy bundles that each party represents, the nature of bipartisanship, or the conventional wisdom about what it takes to win an election can all adjust as the country changes. Why We’re Polarized is effective at explaining how we’ve become split in such strongly emotional ways, but it’s less convincing about how inevitable this reality is to go on. Time will tell whether the seeds he describes will give way to the legitimacy crisis he predicts.

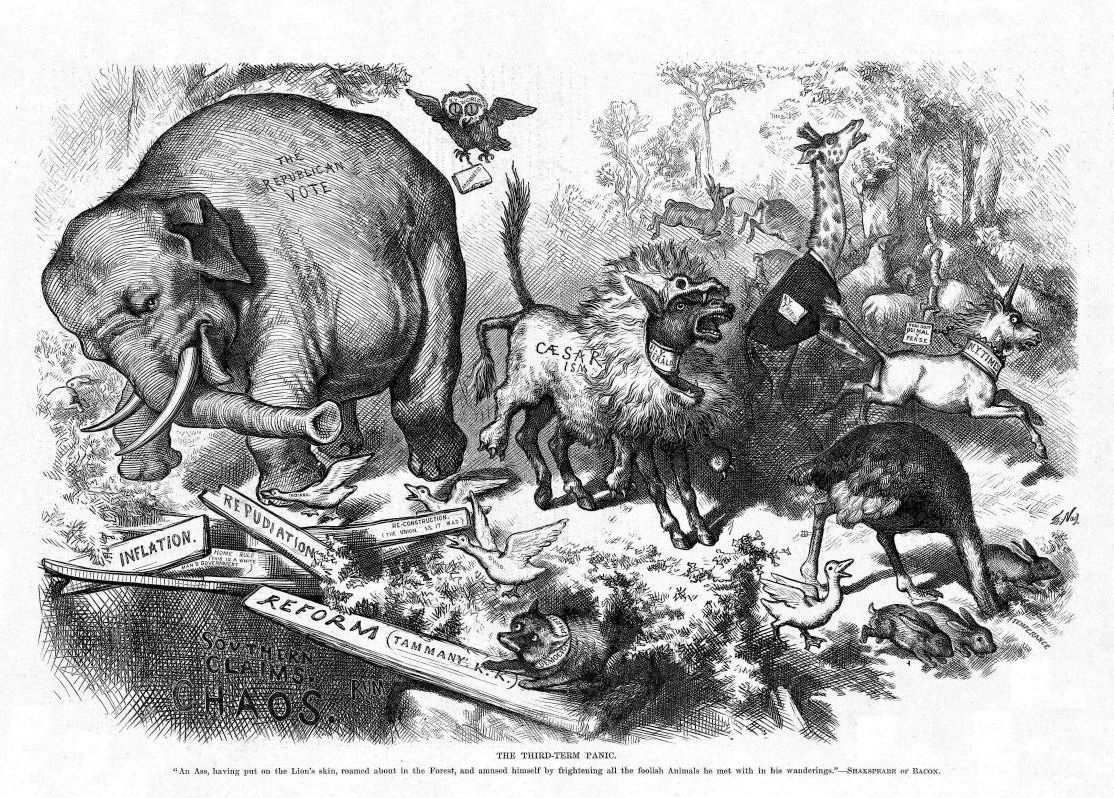

Featured image is The Third Term Panic, by Thomas Nast