The Utopianism of the Meritocrats

The psychological and historical appeal of meritocracy is inversely proportional to its tenability.

Trumpism has long been characterized by a desperate retreat from the dangers of thinking, making a heavy reliance on cliches a requirement. One of those cliches endlessly parroted by the administration in its attacks on DEI is the need to return to meritocracy. America it seems has abandoned the conviction that the best and brightest ought to be rewarded for pulling themselves up by their bootstraps. Instead a corrosive, egalitarian kind of identity politics has replaced the meritocratic ideal with one where rewards are to be distributed on the basis of racial grievance and victimization. Higher education guru Chris Rufo, who manufactured the controversy towards a consciously underdefined “critical race theory,” singled out its criticisms of meritocracy for special ire. The late Charlie Kirk had been touring relentless anti-DEI talking points, arguing that if you want to achieve equity you must compromise excellence. Perhaps no one has been more militant on this than Ben Shapiro. In his recent Lions and Scavengers (reviewed here) Shapiro divides the world into the meritorious Simbas and parasitic Scars, and describes anyone who challenges meritocratic mythologies as petulantly rebelling against God.

Individuals are equal in their rights but not in their qualities. I have the same rights that you do, but that does not mean that we each have precisely the same earning capacity. LeBron James and I have the same rights, but he is a far better basketball player than I am; meanwhile, I’d venture to say that I’ve probably read a few more books cover to cover than he has. That isn’t unjust—unless by unjust, we simply mean that we wish that God had made us all identical in every way at the outset of life. And if that’s our complaint, we ought to grow up. Anger at God for not making the world the way you want it isn’t justice. It’s arrogance, stupidity and childishness. (p. 68)

Rufo, Kirk, Shapiro et al.'s requisite indifference to precision notwithstanding, it has to be recognized that “meritocracy” is a term with many different meanings. In this essay I will not be discussing conceptions of meritocracy that center on the economic and practical importance of appointing people to positions to which they're suited; what one might call a competence-based version of meritocracy. Surgeons performing surgery ought to be hired on the basis of their professional merits. I will also not be addressing Nozick-style libertarian arguments—which differ from those appealed to to defend meritocracy but often overlap with them—about an entitlement to keep what one earns as the result of free and consensual exchange. Instead this essay will be narrowly tailored to criticizing the still enormously popular idea of meritocracy as a system which rewards the deserving while (and this dimension is often less discussed) withholding rewards from the undeserving. This is very much a moral idea, often promoted, which holds that egalitarianism challenges meritocracy by trying to take from the deserving to put them on the same level as the undeserving.

The American origins of meritocracy

The contours of this meritocratic conception go well back in American history. In Federalist no. 10 Madison often reads a great deal like a Marxist social theorist who believes the ruling classes should win. Anticipating modern meritocratic arguments, Madison writes

Diversity in the faculties of men, from which the rights of property originate, is not less an insuperable obstacle to a uniformity of interests. The protection of these faculties is the first object of government. From the protection of different and unequal faculties of acquiring property, the possession of different degrees and kinds of property immediately results; and from the influence of these on the sentiments and views of the respective proprietors, ensues a division of the society into different interests and parties.

While there are many reasons a society might factionalize, Madison warns that the “most common and durable” are inequalities of property. From these inequalities arise different interests, with the rich having an interest in maintaining their earned wealth and the poor having an interest in fleecing the rich. Indeed so intense were the animosities generated by class conflict that the “regulation of these various and interfering interests” was taken by Madison to be “the principal task of modern legislation.”

Madison was not the only founding father to lean into these proto-meritocratic sentiments. In an 1813 letter to John Adams founding father par excellence Thomas Jefferson cast shade on what he termed “artificial aristocracy” while insisting that there was nevertheless a

...natural aristocracy among men. The grounds of this are virtue and talents. Formerly bodily powers gave place among the aristoi. But since the invention of gunpowder has armed the weak as well as the strong with missile death, bodily strength, like beauty, good humor, politeness and other accomplishments, has become but an auxiliary ground of distinction. There is also an artificial aristocracy founded on wealth and birth, without either virtue or talents; for with these it would belong to the first class. The natural aristocracy I consider as the most precious gift of nature for the instruction, the trusts, and government of society.

The modern contours of this meritocracy of desert was well captured by Barry Goldwater (really ghostwriter Brent Bozell) in The Conscience of a Conservative. There he criticized graduated taxation as an “artificial device” contrary to the “laws of nature” because it redistributed from the worthy wealthy to the unworthy poor.

The graduated tax is a confiscatory tax. Its effect, and to a large extent its aim is to bring down all men to a common level. Many of the leading proponents of the graduated tax frankly admit that their purpose is to redistribute the nation’s wealth. Their aim is an egalitarian society—an objective that does violence both to the charter of the Republic and the laws of Nature. We are all equal in the eyes of God but we are equal in no other respect. Artificial devices for enforcing equality among unequal men must be rejected if we would restore that charter and honor those laws.” (p. 62)

This mystical and gishgalloping language of Goldwater/Bozell’s assertion—which references constitutionalism, the laws of nature, and God in quick succession—already gives a clue as to the highly ideological quality of many arguments for this meritocracy of the worthy. Very little is explained. For instance, why a redistributive tax is an “artificial device” to be rejected but taxes for the high levels of military spending Goldwater supported are not an “artificial” device to maintain a disequilibrium of American military power relative to its rivals is unanswered. Nor is what is meant by the “laws of Nature” ever explained. Even as a flourishing gesture to the conventional wisdom of the Founders it falters. After all Thomas Paine, author of Common Sense and The Rights of Man was one of the first to suggest it was actually property that was an artificial, social institution for which the rich owed society a debt.

As Max Weber noted in “The Social Psychology of World Religions,” the intransigence of these sentiments likely owes less to their logical, empirical or historical plausibility than their psychological appeal.

The fortunate man is seldom satisfied with the fact of being fortunate, beyond this he needs to know that he has a right to his good fortune. He wants to be convinced he deserves it and above all that he deserves it in comparison with others. Good fortune, thus wants to be legitimate fortune.

The utopianism of meritocracy

At the epicenter of the desert-based conception of meritocracy is a seemingly simple idea: that the good things in life, whether money, status, or honors, should flow to those who deserve and have them. Inversely, the good things in life should not flow to those who don’t deserve them. At its most pointed one might even desire that bad things flow to the undeserving. This seemingly simple idea typically originates in individual circumstances, where proximity makes it easier to assume who deserves what, and is then generalized to society as a whole. A well-functioning meritocratic society is one so organized as to ensure the good things in life by and large go to all the deserving, while fewer good things or even bad things go to the undeserving.

As Weber notes the psychological appeal of this vision, especially to those who have succeeded, is enormous. A combination of this psychological appeal and the deep historical roots gestured to likely explain its borderline common sense appeal. Indeed the idea of a desert-based conception of meritocracy is so deeply ingrained, even hardened egalitarians like Ronald Dworkin struggle to entirely give it up.

What is rarely acknowledged is that the psychological and historical appeal of meritocracy is inversely proportional to its tenability. It is in fact hard to imagine a much more utopian idea that has even been posited than meritocracy. From St. Augustine through the church fathers there is a deep drive in Western thought to imagine a world so well-organized that in the end each person will get what they truly deserve. The idea of heaven and hell speaks to this need. But the Church fathers were wiser than many of us in cautioning that such a world was not possible in this life, where the rain fell on the just and unjust alike. It was not within human power to give to each what they deserved or didn’t, let alone to design and establish such a society. Only God had the requisite knowledge, power and wisdom.

Even socialists and communists have been less ambitiously utopian than the hardened Shapiro-type meritocrat. In the “Critique of the Gotha Programme” Marx presents his distributive principles as being “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.” Many conservatives have lampooned the idea of society where each and everyone’s needs were met as cartoonishly unrealistic. And yet conceptualizing and provisioning what people need is a far less abstract task than somehow ascertaining what each person deserves, and giving it to them. For many today, somehow the invisible non-intelligence of the market is supposed to spontaneously do what it was once thought only the visible hand of God’s absolute intelligence could do: establish a society where each gives according to his merits, and receives according to his just deserts.

The two greatest liberal thinkers, on opposite ends of the political spectrum, reached critical conclusions about meritocracy nearly simultaneously in the mid-20th century. Best known is Rawls’ account in A Theory of Justice, which was directed at criticizing the more conservative versions of the meritocratic argument. For Rawls meritocrats missed the extent to which outcomes in life were enormously determined by morally arbitrary factors. First one’s natural talents or disabilities were the result of a genetic lottery, meaning one deserved neither commendation or condemnation for possessing them. Secondly, some people began life with enormous social advantages and others with enormous social disadvantages. In contemporary American society many grow up in highly affluent homes, are provided with every resource in private schools, and are tutored on how to get into the Ivy League. Others grow up in households where there is barely money to keep the water running, and they’re told to get a dead end job early to help keep the family floating above water. These circumstances have ripple effects throughout life. Finally, the ability to profit from one’s developed talents itself is contingent on being fortunate enough to live in a society where there is a market for those talents. A person who grew up with natural talent for hockey his parents had the money to foster might end up a millionaire NHL player if he was lucky enough to be born near where I grew up in Stittsville, Canada. The exact same person born into a supportive family in Tunisia will end up with an eccentric hobby. Taken together Rawls’ pointed critique is that we have very few reasons to imagine any society could be a meritocracy; the rule in life is there but for the grace of God go I.

Less well known is F.A. Hayek’s critique of meritocracy in The Constitution of Liberty: The Definitive Edition. Hayek is largely not responding to conservative proponents of meritocracy, but their egalitarian critics who defend redistribution on the basis that it would in fact be more meritocratic. There is a longstanding debate in Western philosophy, well traced by Elizabeth Anderson in Hijacked, around the work ethic. This has deep links to the desert-based conception of meritocracy, with right-wing versions of the work ethic arguing the rich deserve more given their superiority and efforts. It was this version Rawls largely targeted. The left wing version of the work ethic inverts the moral argument, holding that it is the working class that deserves more given it does most of the actual labor in society and currently reaps far less of the reward. Aligned with this is the supposition that the working classes are morally superior to the rich. Critics like Jordan Peterson often wrongly associate this kind of sentimentalist attitude towards labor and the working class with Marx. In fact it was probably given its best exposition by Ricardian and Christian socialists like R.H. Tawney who argued that if labor really produced value and entitlement to property then the undeserving rich were effectively stealing from the productive workers who actually labored to produce commodities of value. In The Acquisitive Society Tawney called for a transition to a functionalist principle of distribution where people would actually be rewarded based on their efforts, which he argued would entail the poor getting a far bigger slice of the pie.

Hayek wished to rebut this left wing view that the poor and working were deserving of more given their disproportionate efforts relative to the often idle rich. This led him to a rejection of meritocracy. He pointed out that in a free society people would be rewarded based on the value they produced through gratifying the subjective desires of consumers. The result would often look patently unfair, with the undeserving getting ahead while the hard working and even talented slipped behind. Fifty Shades of Grey will sell millions of copies and make E.L James rich while generations of talented novelists like Hermann Melville will die poor. It didn’t even seem to correspond to the “objective” value of what one produced. In a market society pediatric nurses will earn a middling income saving the lives of children day in and out while the brownnosing Daily Wire crowd will reap millions from grateful billionaires. Wal-Mart cashiers will work long hours and struggle to get by, while the Walton family coasts on billions in inherited wealth. A fermenting cheese can end up President while more morally virtuous figures spend their days volunteering in soup kitchens. Correcting for these clear deviations from merit would require mass intervention by the state to give to each what they deserve, to Hayek’s mind interfering with the free outcomes of exchanges based on gratifying subjective preferences.

Hayek’s point is less systematic and clear than Rawls’ but he does add something that Rawls doesn’t. Drawing on his longstanding anti-utopian reservations and skepticism about the ability of human beings to design society, he detects the utopian qualities inherent in any version of the desert-based conception of meritocracy. It simply is impossible, and very likely undesirable, to aspire to such an ideal, because it would require state engineering on a mass scale and well beyond what human beings could intelligently put into practice.

A society in which the position of the individuals was made to correspond to human ideas of moral merit would therefore be the exact opposite of a free society. It would be a society in which people were rewarded for duty performed instead of for success, in which every move of every individual was guided by what other people thought he ought to do, and in which the individual was thus relieved of the responsibility and the risk of decision. But if nobody's knowledge is sufficient to guide all human action, there is also no human being who is competent to reward all efforts according to merit. (The Constitution of Liberty p. 161)

One can put this a somewhat different way in the same register. In Anarchy, State and Utopia the great libertarian thinker Nozick claimed “liberty disrupts patterns.” That is, allowing free individuals to engage in exchange will always lead to deviations from any intellectualized conception of justice you want to impose on society. Nozick’s target, like Hayek’s, was the egalitarian who wants to bring everyone to the same starting point. He pointed out that left to their own devices, even economic equals would pay stars like Wilt Chamberlain money and help him get rich. The same reasoning applies to the ultimate and most utopian of patterned theories of justice: desert-based meritocracy. Left to their own devices rich parents will leave money to trust fund kids, consumers will reward inferior products and their producers because of slick or misleading marketing, grifters will often strike it rich, and Disney will make billions off another remake of their classic filmography. It would take immense social engineering for the meritocrat to even partially and very imperfectly impose and then constantly reimpose their preferred pattern of merit.

What would a meritocratic utopia require?

Hayek is undoubtedly correct in many of his claims; something his fans on the right like Shapiro have struggled to acknowledge. But one might rebut that even if a true meritocracy is impossible we still ought to aspire to it. Aspiring to the perfect can still result in producing the good. To my mind, given Rawls’ objections especially, this kind of special pleading ultimately looks a bit like saying even though we can't have square circles we still want square circles so badly we should aim for them. Let's entertain this idea for a while. What would it take to genuinely establish a meritocratic utopia where each gave according to his merits and received according to his just desserts?

Most obviously, contra Kirk and Rufo’s claims, it would require massive and intense redistributions of wealth, privilege and power. Indeed redistribution on an unprecedented scale. This point was well captured by Kimberlé Crenshaw, critical race theorist par excellence and founder of intersectional theory. She asks us to imagine America as a competitive race where some people start several hundred yards ahead of the line. This corresponds to the advantages accrued by, say, the white population which by and large enjoys enormous amounts of generational wealth racial minorities don’t have. But it could also correspond to other advantages that operate along gender, class, etc lines. Now a race in which some start with these advantages is clearly not genuinely fair, given the advantaged will very likely end up winning and the disadvantaged lose for reasons that have nothing to do with ability, drive, athletic talent etc.

For the race to actually be meritocratic and reward the “best” runners, everyone would need to be brought to the same starting point. Corresponding to actual society this means that to design (and that is what it would amount to) a truly fair and competitive meritocracy, we would need to go well beyond purely formal equality of opportunity where everyone can nominally compete but at very different starting points. All unearned advantages would need to be eliminated and disadvantages that aren’t related to individual drive, talent, ability would need to be radically compensated for. Only then would the truly “best” fairly win the race of life.

It is staggering to imagine the level of state intervention that would be required to achieve this, let alone the degree of intrusion. As Hayek would note it's not clear it would even be possible given the intelligence required, and it is certainly not prima facie desirable. But it is what would be required to even approximate for a moment the meritocratic ideal, which should demonstrate once and for all just how fanciful it truly is. Moreover after each race was won, we’d need to reset new participants to the baseline to ensure unearned advantages or disadvantages don’t reappear and compound. In Goldwater’s terminology, anything approaching meritocracy would require “artificial” devices beyond count.

Interestingly Crenshaw applies the “race” metaphor to argue for affirmative action. Not because it contravenes meritocratic principles, but in part because she thinks meritocracy requires it. And in some respects she’s right for the reasons mentioned. One can’t run a series of profoundly unfair competitions, where some are immensely advantaged and others comparatively disadvantaged from birth by virtue of racial characteristics and prejudice, and call that a fair competition. In this respect some form of affirmative action or leg up to compensate for unfair disadvantages is actually required to get marginally closer to the meritocratic ideal. The irony is that just as socialists like Tawney took more seriously than pro-capitalists the principle that hard work should be the basis of reward, Crenshaw takes the idea of meritocracy more seriously than Shapiro, Rufo and the rest of the boys. She actually has some sense of the enormous redistributive and social changes that would be needed to even partially achieve it and is willing to sign off on them.

But I think Crenshaw is wrong to think that our ideal should be a society where we still have competitive races, but everyone is brought to the same starting point on the line. Firstly, as mentioned, taken seriously it would require enormous state reorganization to accomplish this along every meaningful “intersectional” metric. But secondly, because I think even if accomplished the kind of society that emerged would be even more unpalatable. Per Michael Sandel’s The Tyranny of Merit we already have a ruling class in this country that applauds itself for possessing unearned merits which it owes to no one else, and inversely a working class that is often demonized unfairly as lazy and demanding. This has induced enormous feelings of ressentiment. If we were to accomplish Crenshaw’s goal of bringing everyone to the same starting point along every intersectional metric, the race of life would be somewhat closer to a fair competition. The results still wouldn’t be very close. Morally arbitrary natural inequalities would still play an enormous role, and we’d have to debate the extent to which society was also responsible for that. But we’d be roughly closer, if still far away, from the meritocratic ideal.

In this scenario it is likely the already intense and socially corrosive feelings of ressentiment would only intensify. The winners of life would feel socially even more assured that they truly owed nothing to anyone else, and the losers that they alone were responsible for winding up working as a Daily Wire intern forced to listen to Matt Walsh all day. For a liberal egalitarian this situation is unjust in not acknowledging the enduring depth and expanse of our duties to the least well off, and also fails to recognize the extent to which it's moral arbitrariness the whole way down.

Conclusion

One of the best arguments for liberal egalitarianism is that it finally dissolves the abstract aspiration for meritocracy in favor of a more realistic worldview. There will never be a society where people get anywhere close to what they “deserve” even if people truly want it very badly. It isn’t clear to me how that could even be defined, given the enormous complexity of even a single life with all the ups and downs of our interactions. We are each of us so intimately enmeshed in the fabric of family, friends and community it is often hidden where we wound and where we console, where kindness becomes condescending pity and expectation curdles into venomous resentment. What we can have is a society that treats people fairly by securing for them what they need. And you know what they say about the wisdom that comes from realizing you will not be getting what you want, and the virtue shown in gratitude at getting what you need.

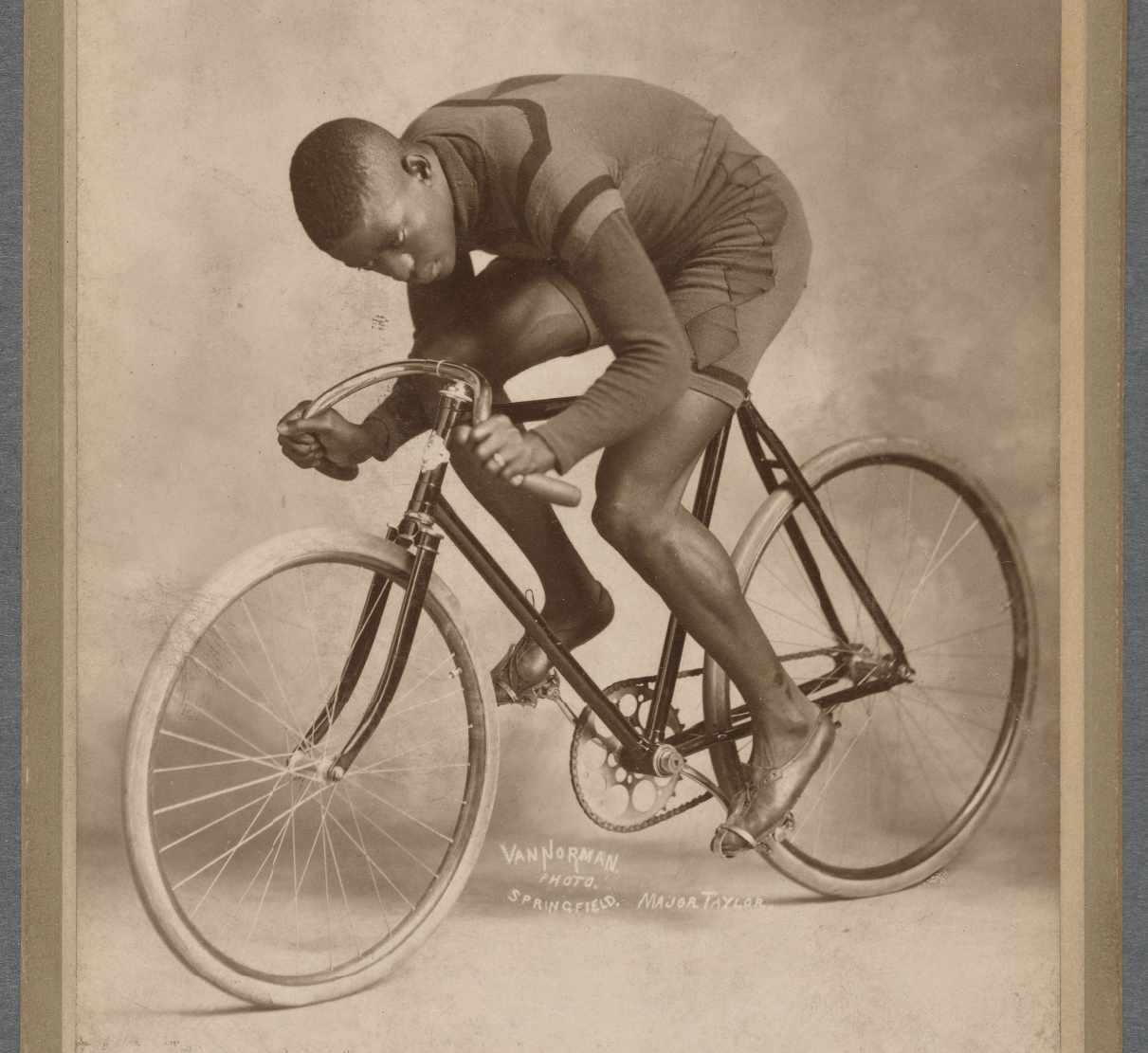

Featured image is "Major Taylor," George H. Van Norman 1898