When Words Are Stolen

The real stakes of semantic fights.

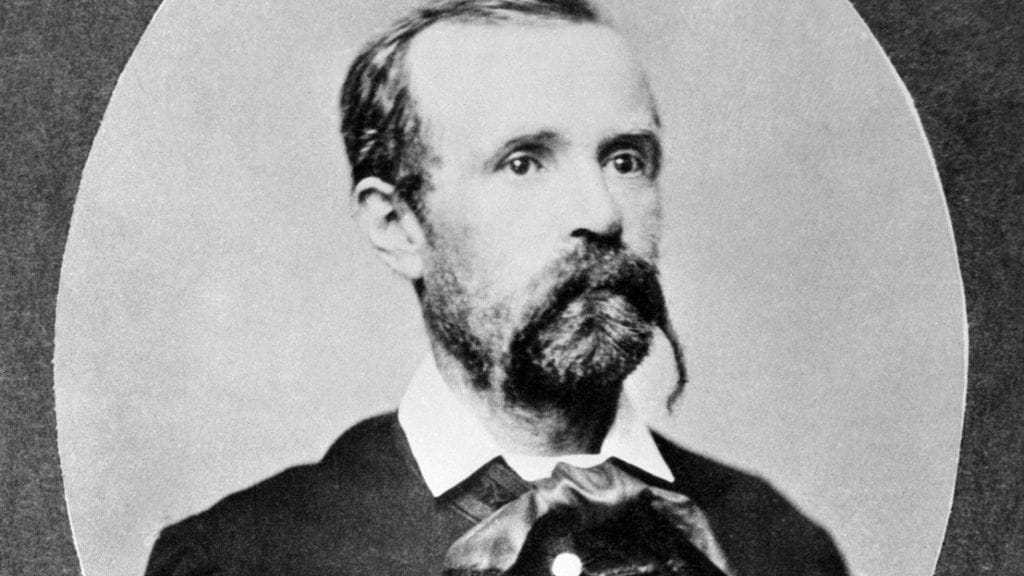

In the 1850s, veteran of the 1848 French Revolution Joseph Déjacque was exiled in New Orleans. His ideas were radical. At a bar in Royal Street, he called on slaves to arm themselves and overthrow the US government. He advocated for gender equality, the abolition of the family and of religion, and a post-racial America based on a transracial working class coalition.

Somewhere in his large body of writing, he thought of using the term “libertarianism”—which had previously referred exclusively to a metaphysical view that upholds the existence of free will—to refer to his belief that liberty requires abolishing both private property and the state. The name took off, and for good reason. “Libertarian” provided an immediate connection between these radical political ideas with the widely shared value of liberty.

This connection made the term an envied possession—especially by those who saw the rabid defense of private property as the key to liberty. Eventually they managed to “capture [this] crucial word from the enemy,” in the words of Austrian School economist Murray Rothbard. In doing so, those we now call libertarians connected the value of liberty with private property. Those who opposed private property lost: their view is now labeled as anarchism, a term that suggests chaos and instability more than freedom.

Words can be banned: indeed, we are witnessing this in the Trump administration’s ban of heretofore apolitical words (from “women,” to “pronouns,” to “safe drinking water”) from research projects. Power can also operate by inventing new words to frame a situation in favorable ways: when Lee Atwater infamously recommended framing racist policies in terms of “states’ rights” in 1981, harking back to terminology from the Civil War, he invented a new way to mask racism, thus making racist policies harder to contest.

But what happened with “libertarian” was different. It was a power struggle over who gets to claim a word and what it gets to mean. And it ended with the word being stolen: twisted away from its original meaning at the service of a specific agenda, and leaving others with impoverished resources for communicating their position.

The Trump administration, too, is stealing words. When DOGE tweets “Grant awards will be based on merit, competition, equal opportunity, and excellence” (as it does more or less daily), this is a move in the long game of stealing words like “merit,” “equal opportunity,” and “excellence.”

Having merit used to mean that a person possessed the skills required to succeed in the professional position they were in. These days, however, merit is repeatedly contrasted with DEI, which at one point stood for diversity, equity, and inclusion but is increasingly a rightwing bogey. This sets up the fallacious inference that anyone other than white men don’t really deserve their jobs. This new frame thwarts the original meaning of “merit.” Historically as well as currently, white men are the demographic most often hired precisely because of their race and gender, not merely because of their merit.

When DOGE frames grant cuts and the firing of people perceived to be hired for DEI considerations, as promoting “merit,” this has immediate costs. The appeal to merit makes it harder to argue back: who wants to argue against a measure that promotes merit? And how are we to do so without appearing to be in favor of incompetence and bias?

These small, local thefts of words can have dire implications when repeated. A word can come to acquire strong associations with these distorted uses, and lose its earlier, useful meaning. Our collective resources for expressing ideas become impoverished, and we are left struggling to articulate what we really mean. We no longer have the words.

Arguably, we are at an advanced stage of this process with the term “efficiency.” The word “efficiency” used to refer to the ability to achieve a desired result with the least waste of time, effort, or resources. In this framing, everyone, even progressives, wants efficiency in government. But now that “efficiency” is in the very name of a dubious organization destroying the federal government, calls for efficiency usually serve as a demand to shrink or dismantle government altogether. Never mind that dismantling an organization is unlikely to make it more efficient in any reasonable sense of the word. DOGE would more aptly be named the Department of Austerity.

Losing the term “efficiency” is costly. It makes it harder to have reasoned conversations about how to manage resources to best achieve collective goals. As the word “efficiency” becomes toxified by its Muskian associations, we might even become suspicious of the core value it represents. In this way, stealing words can erode important values.

Everyone recognizes that banning words is a clear attack on our freedoms of thought and speech. So too is the act of stealing words by distorting their meanings, and for similar reasons: in both cases, we lose words that we need to think and communicate about the world. As we lose words, we lose our ability to bring a shared reality into focus—a prerequisite for having any productive discussion.

The good news is that we can resist this attack on our freedoms. It won’t be easy. Power and money make it easier to “flood the zone” with framings of choice. But collectively we have some options.

One thing we can do is insist on rigor. “If politicians, journalists, and even kitchen-table debaters adopted the habit of defining their terms, we would understand each other better—and begin the process of restoring language” suggests activist and journalist Masha Gessen in their 2020 book Surviving Autocracy.

As philosophy professors, we are obviously enthusiasts of this proposal. But we think it is also limited. Once a word has been stolen—as “libertarian” has—insisting on the use of an earlier meaning is pointless. And even when an earlier meaning is still a contender, many people have little patience for listening to definitions and tracking them carefully in conversation (trust us, it’s our job to try to get people to do this in the classroom).

Fortunately we have other resources. We can try collective counter-insurgency: to use the term that is under attack in our ways. For example, if “efficiency” is under attack, we can flood the public sphere with competing uses: describing social democratic governments, public healthcare, public education, and so on (accurately) as efficient. In doing so, we can insist on the value that efficiency can have when at the service of the collective good. This can help keep the term from sliding into a new meaning—and it can help us keep sight of what we value.

This strategy can be paired with efforts to block attempts at capture by offering our own alternative framings. We might frame DOGE’s actions as the destruction of our collective institutions and as imposing chaos and instability—framings that are incompatible with efficiency. Or we might employ mockery and sarcasm to make the framings favored by Musk et al. seem ridiculous—pointing out, for example, that efficiency tends to be incompatible with the use of ketamine (Musk’s confirmed drug of choice). The goal with both strategies is to keep the “efficiency” framing of DOGE from sticking, stopping the capture of the term in its tracks.

Even when a term has been captured, this doesn’t need to be the end of the story. Instead, we can take a page from strategies of appropriation and collective creativity that marginalized groups have long engaged in. A term that is stolen is not necessarily stolen forever. It can be reclaimed, like derogatives ranging from “queer” to “redneck” have been. It is less common to reclaim labels for political views or for values, but it can at least be attempted: perhaps “efficiency” could be won back to denote a state that actually meets its citizens' diverse needs, and “merit” to denote those who become highly skilled, especially if this required surpassing sizable obstacles.

Finally, language is not static: we can repurpose existing terms, like Joseph Déjacque did with what was then the obscure philosophical term “libertarianism.”

We can also invent new terms. When feminists came up with the term “sexual harassment” in 1975, they empowered many people, in particular many women, to understand and communicate the seriousness of previously invisible experiences that were hampering their success in the workplace. These new words led to a new legal framework, and, ultimately, to significant cultural changes that allowed many women to participate more fully in society.

Similarly, reframing the minimum wage as a living wage emphasizes dignity and everyone’s right to meet their basic needs, shifting the terms of the debate. Perhaps new, better words that better highlight our values can be introduced to replace those stolen by bad actors.

Whatever strategies of resistance we use, they need to be collective. Words are collective goods: they let us communicate with one another precisely because they exist between us instead of belonging to any one person. Together, we can protect and construct language that helps us see the world clearly—as long as we attend to the ways in which it is under threat, and remain focused on articulating our values.

Support Liberal Currents

Become a patron or make a one-time donation today.

Featured image is Joseph Déjacque