Defending Hierarchy: the Conservative Impulse

It is allegiance which defines the condition of society, and which constitutes society as something greater than the ‘aggregate of individuals’ that the liberal mind perceives. It is proper for conservatives to be sceptical of claims made on behalf of the value of the individual, if these claims should conflict with the allegiance necessary to society, even though they may wish the state (in the sense of the apparatus of government) to stand in a fairly loose relation to the activities of individual citizens. Individuality too is an artifact, an achievement which depends on the social life of people.

Roger Scruton, The Meaning of Conservatism

Since at least Trump’s election in 2016, the question of what separates conservatism from liberalism has gained renewed importance. It’s not an easy task since even the term “liberal” has different meanings in American political culture. On the right, “liberal” has often been used as a pejorative slur second only to “socialist” in the contempt it evokes. On the other hand, many prominent intellectuals on the political right—particularly those who identify with the Intellectual Dark Web—proudly identify as “classical liberals” while launching into their 50th tirade about allegedly illiberal or authoritarian college students. Sometimes conservatives are portrayed as the most determined defenders of liberal values like free speech and association; locked in fierce battle against the censorious left and its growing list of cultural and market allies. But on the other hand there is a burgeoning movement of “post-liberal” conservative thinkers who openly flirt with integrating Church and state.

In this article, I will draw a sharper conceptual contrast between liberalism and conservatism as they emerged historically and operate contemporaneously. The fundamental distinction between conservatism and liberalism is the former’s commitment to moral inequality. Conservatives are simply more comfortable with the idea that people are unequal, and so should be treated unequally. This idea takes more and less extreme forms, with moderate conservatism overlapping closely with right wing variants of liberalism. But in its most reactionary forms, conservatism can give an almost metaphysical grandeur to the inequalities that exist between people. I will conclude by arguing, as I’ve discussed elsewhere, that the more liberals become convinced that moral equality must entail high levels of material parity the more likely they are to affiliate with socialist ideals. Because I think ultimately the idea of moral equality necessitates securing for all individuals a comparable—though not equal—set of capabilities needed to live a good life, liberals should gradually come to gravitate more towards these progressive positions.

The idea of moral equality

The historical relationship between moral equality and liberalism is complex, but can be boiled down relatively simply. The Scruton epigraph discusses the liberal’s individualism and their consequent wariness of the notion of “allegiance.” Elsewhere in The Meaning of Conservatism Scruton stipulates how this cashes out as an “attitude of respect towards individual existence—an attempt to leave as much moral and political space around every person as is compatible with the demands of social life. As such it has often been thought to imply a kind of egalitarianism. For by its very nature, the respect which liberalism shows to the individual, it shows to each individual equally.” Scruton is exactly right on this point, and as we shall see it is conservatism’s insistence that respect needn’t be paid to all individuals equally that lies at the root of its dispute with liberalism (and by extension, socialism).

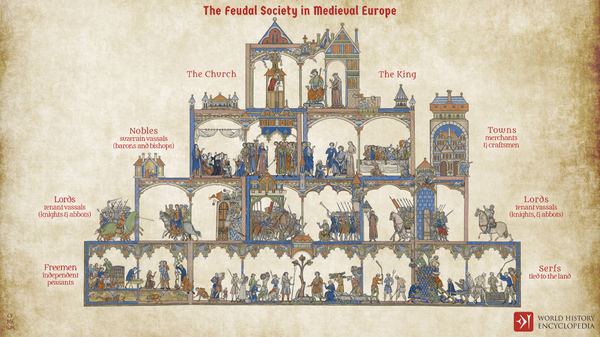

The idea of moral equality has deeper, and less secular, roots than liberalism of course. The Buddhist Emperor Ashoka reflected the ideal in his injunction to tolerate and learn from sources of wisdom wherever they may come from. The Roman stoics, who profoundly influenced liberals like Adam Smith, often insisted that slaves and emperors live, age, and die alike. And at its best the Christian Scholastic tradition taught that all of God’s children were equal in His eyes. But these doctrines confronted a broader consensus of learned opinion that people were, either by nature or by divine fiat, fundamentally unequal. Consequently, it is both inevitable and desirable that society should reflect these inequalities in how wealth and power are allocated. In the Republic Plato famously distinguished between people with souls of bronze, of silver, and of gold, and insisted only the latter were fit to rule. If the wrong souls were somehow to rule, the city would be doomed. Aristotle similarly ranked people according to their virtues and natural capacities, infamously declaring many to be “natural slaves” fit largely for the manual labor which would enable their betters to pursue higher and more virtuous ends. In the medieval and early modern era, religious defenses of both feudalism and later absolutism stressed both the naturalness and divine necessity of social stratification. Sir Robert Filmer’s Patriarcha, scathingly criticized by none other than John Locke, defended the divine right of kings through a mix of both: arguing that God granted initial authority to a series of Biblical patriarchs, who passed it along through their biological descendants.

Early and proto-liberals attacked the claim that society should maintain calcified distinctions of wealth and power from a variety of different angles. At the basis of their argument was the claim that, at least in the proverbial beginning, all human beings were morally equal. This did not mean society required everyone to be equal in fact, but it did problematize the idea that the proper kind of social stratification was set once and for all by natural or divine ordinance. Hobbes—not a liberal himself but a deep influence on the tradition—mocked the aristocratic ethos of Plato and especially Aristotle as so much nonsense, and insisted that in the state of nature all of us were conspicuously equal. Most notably this included in both our bodily and especially mental faculties; contra the ancients, Hobbes maintains that “as for the faculties of the mind: I find that men are even more equal in these than they are in bodily strength.” In the Second Treatise of Government, Locke reiterates his critique of Filmer and insists that the state of nature “is also a state of equality in which no-one has more power and authority than anyone else; because it is simply obvious that creatures of the same species and status, all born to all the same advantages of nature and to the use of the same abilities, should also be equal…” In the next century in her Vindication of the Rights of Women Mary Wollstonecraft eloquently chided her liberal counterparts for not applying such principles with the barest consistency, speaking “in defence of that half of the human race, which by the usages of all society, whether savage or civilized, have been kept from attaining their proper dignity—their equal rank as rational beings.”

This latter point brings us to the most noxious feature of liberalism’s history, which is the self-serving tendency of its exponents to preach moral equality while carving out gigantic exceptions where it was expedient. The American Founders were a spectacular example, with many of them owning slaves, and the pious democrat Thomas Jefferson seeing nothing wrong with sexual abuse. The post-colonial theorist Uday Mehta has drawn attention to the fact that J.S. Mill, a highly admirable liberal socialist in most other respects, nevertheless held condescending views towards the colonized peoples of the British empire. These compare unfavorably to those of the conservative Edmund Burke, who was more sensitive to the cultural differences of the Indian subcontinent.

Notably the commitment to moral equality did not mean that liberals were initially committed to material or even political equality for all. As I’ve discussed elsewhere, echoing C.B. Macpherson, most early liberals were “possessive individualists.” They felt that the old naturalized hierarchies should give way to a more dynamic society where social stratification would be determined through competition in the market, rather than something as arbitrary as aristocratic privilege. This persists down to the present day, with neoliberalism constituting the most radical form of possessive individualism we’ve yet seen. Liberal possessive individualists may accept the need to end legal discrimination against groups, which keeps them from participating as formal equals in the market. But they are generally wary of taking too many steps to compensate members of discriminated groups on the basis of what Hayek called the “mirage of social justice,” and absolutely do not think there is any entitlement to the political provision of high levels of material well being for all where that would contravene the efficient mechanisms of the market.

Possessive individualism’s emphasis on the importance of property and the competitive market is the variation of liberalism with which many conservatives have felt the deepest elective affinity. Right wing liberals like F.A. Hayek and Michael Oakeshott returned the love by emphasizing the importance of law, order, and tradition in stabilizing capitalist societies and providing a sense of humanistic attachment above and beyond market relations. They also sometimes worried, like Alexis de Tocqueville in Democracy in America, that liberalism would give into a levelling impulse that would gradually erode the striving for excellence and status upon which social progress and high culture depended. But there was always a resistance against moving too far in the direction of inegalitarianism; or as Hayek put it in “Why I am Not a Conservative,” even right wing liberals must reject “the conservative position … that in any society there are recognizably superior persons whose inherited standards and values and position ought to be protected and who should have a greater influence on public affairs than others.” It is this denial that there are “recognizably superior persons” that makes one a liberal and not a conservative.

Conservatism and inequality

Oddly enough conservatism was the second, not the first, major modernist doctrine to emerge. This is ironic since conservatives often hold themselves to be defending more ancient and enduring values than their liberal and certainly socialist counterparts. And indeed conservatives continue to find more use in the authors of antiquity than liberals or socialists; whether one talks about Aristotle, Confucius, or any of a million strands of quasi-Thomism. But as a distinct body of thought modern conservatism emerged in response to the liberal and democratic movements of the 18th century, which they initially saw as a concerted threat to well-established political hierarchies.

This responsiveness to events, the reactionary disposition as it is sometimes called, means that conservatism is far more eclectic than either liberalism or socialism. This is sometimes explained away as arising from theoretical differences. According to Russell Kirk, unlike liberals and socialists who are committed to abstract principles, the conservative is motivated more by a disposition or attitude than anything else. In “On Being Conservative” Michael Oakeshott framed it more nostalgically, claiming “to be a conservative … is to prefer the familiar to the unknown, to prefer the tried to the untried, fact to mystery, the actual to the possible, the limited to the unbounded, the near to the distant, the sufficient to the superabundant, the convenient to the perfect, present laughter to utopian bliss.” This preference for the familiar and “actual” is indeed emblematic of conservative thought, and why they often rightly claim to be more “realistic” in a narrow way than their liberal or conservative counterparts.

Since conservatives tend to be attracted to defending existent divisions of wealth and power, they can usually claim to be merely upholding the world as it is rather than speculating on an “abstract” (there is that word again) or utopian world to be. But this realism doesn’t run very deep, since the world never simply “is” but is always in a process of becoming. When Marx critiqued his opponents for their philosophical “idealism” this is what he had in mind; conservatives idealize a state of affairs they take to be reflective of some deeper, more natural, or holier reality and resist any tendency on the part of the material world to transition away from this idealization. Consequently the alleged “realism” of conservatism often turns out to be a kind of sublimated idealization, which not coincidentally is why conservatives since Edmund Burke have always been attracted to aesthetic and religious imagery and ideas, which seem to sacralize their preferred social order. This view is something that must be felt and venerated rather than questioned, or as Joseph de Maistre put it,

government is a true religion: it has its dogmas, its mysteries, and its ministers. To annihilate it or submit it to the discussion of each individual is the same thing; it lives only through national reason, that is to say through political faith, which is a creed. Man’s first need is that his nascent reason be curbed under this double yoke, that it be abased and lose itself in the national reason, so that it changes its individual existence into another common existence, just as a river that flows into the ocean always continues to exist in the mass of water, but without a name and without a distinct reality.

Power is generally sublimated into authority, and consequently either to be unquestioned or at best justified through apologias. Any effort to intellectualize power risks desublimating its authority and turning it into a matter of debate, or worse, voluntarism. This is one reason J.S. Mill snidely claimed “stupid people are generally conservative.” And indeed they can dismiss intellectuals as everything from “sophisters, economists, and calculators” in more elitist moments, and the “anointed” in more populist ones. Oftentimes this wariness of intellectuals is more visceral than thought through; a kind of instinctive response to those who would question the inherited and embedded wisdom carried in conservative traditions and institutions. Sometimes it is theorized in a rather partisan manner. But few are as honest as Roger Scruton in stating the primary reason: too much intellectualism leads people to become unwilling to accept the problems of life and to seek remedy through potentially radical political action. Consequently many conservatives prefer and even idolize an “unthinking” population.

There is a natural instinct in unthinking people—who, tolerant of the burdens that life lays on them, and unwilling to lodge blame where they seek no remedy, seek fulfillment in the world as it is—to accept and endorse through their actions the institutions and practices into which they are born. This instinct, which I have attempted to translate into the self-conscious language of political doctrine, is rooted in human nature…

In moments of political quietism or populism, conservative intellectuals will sometimes heap praise on these “unthinking” masses who know their place and keep the trains running one time. Particularly through contrasting them with ungrateful and resentful “elites”—which typically means liberal and leftist intellectuals and activists. The problem emerges when those same liberal and leftist intellectuals and activists convince the masses through abstract sophistry and other witchcraft that they should seek remedy for their problems in political and economic change. At this point the people quickly become the “swinish multitude” or Nietzsche’s “herd;” driven by resentment, envy, and a yearning to upset the sublimated idealizations of hierarchy dear to the conservative heart. In such moments the real emphasis of conservatism on maintaining existing hierarchies of power and wealth becomes most exposed, and it is at the greatest risk of appearing unpalatably elitist and inegalitarian. Conservative doctrine either naturalizes or mythologizes social differences that liberals and leftists are determined to overcome through reform or revolution.

These differences can take many forms: differences in wealth and political status were the first to be critiqued by liberals and later socialists. But since then we’ve added struggles to ease inequities in gender roles, recognize the equal status of LGBTQ individuals, rights for ethnic and religious minorities, an end to racial hierarchies, recognition for migrants and countless more to the list of egalitarian causes conservatism has at one point or another opposed. Where they become sufficiently threatening, conservatives tend to become self-conscious, and recognize the need to reflect intellectually on their preferred hierarchy to defend them. This is in some respects an uncomfortable position, since it means desacralizing those hierarchies and rendering them open to analysis and consequently criticism. But failing to do this cedes the intellectual high ground to liberals and socialists, who will use it to inspire critical reflection leading to demands for reform 20 years down the line. When too much change has occurred, conservatives will also adopt more radical postures which seem at odds with their usual claim to be persons of moderation and slow reform. One of the reasons illiberal post-modern conservatives like Donald Trump and Viktor Orbán were popular was the feeling that too many privileges and too high a status had been granted to the unworthy; their success owed a lot to an ability to convince citizens that too many people—immigrants, women, minorities—had cut in line and obtained benefits and government mandated advantages that they did not deserve. The same was true of Reagan and his tirades against “welfare queens” in the 1980s. In circumstances where too many gains have been achieved by liberals and leftists, conservatives will engage in anything from radical reforms to outright counter-revolutionary efforts to restore the right kind of social hierarchy to society.

Conclusion: conservatism and liberalism

These conservative impulses are all very different from those of liberals and socialists, who operate on the presumption of moral equality and believe any deviations from equality require justification. For conservatives it is inequality that is the fact of life, either tragically or for the best, and thus efforts to produce artificial equality should be scrutinized. This tends to be reflected most prominently in our contrasting views of authority. For liberals and socialists at their best, moral equality generates a further presumption in favor of the liberty of the individual. Since all people are equal, we should all be equally entitled to pursue our contrasting visions of the good life, and only constrained where absolutely necessary. For conservatives, inequality suggests that some people do indeed know best what should be done. These may be the more virtuous, the stronger, the more patriotic, the more intelligent and religious, or any combination thereof. Typically they will make themselves known by rising or staying at the top of a venerated social hierarchy, whether this is religious authority or the commanding heights of the economy. Conservatives believe the views of these “recognizably superior” persons should naturally be granted greater weight and significance politically, even if these views happen to look like prejudice. Indeed the prejudices that liberals and leftists criticize so furiously may actually reflect a kind of shared wisdom that binds a community together and commits it to higher standards of excellence, which gives way to the anarchy and decadence of levelling when gone.

One thing we may grant to conservatives is the anthropological point that many people may indeed view the world in such quaintly hierarchical terms. There is good biological evidence to suggest we naturally sort ourselves hierarchically, and this doubtless colors our interactions and viewpoints. But I do not think this is nearly as strong a point as they make it out to be, since the liberal and socialist point has never been that all hierarchies are bad. No one should be weeping or marching over the fact that I remain locked in the Bronze League with League of Legends. The argument of liberals and socialists has always been that many of the particular hierarchies that exist right now are neither necessary, useful, nor particularly moral. The latter point about moral equality flows from the conviction that each person’s life is equally dear to them and those who love them. Louis XIV may have loved himself far more than many of servants who doted on him, but that was a blemish first on the narcissistic conceit that being born Bourbon somehow meant God smiled upon you. So there must be very good reasons for why some people are given such a better shot at a flourishing life than others.

Given this, we need pay little mind beyond strategy to the fact that many people are attached to them. That many southern whites, as James Baldwin put it, drew their sense of self-worth from feeling superior to people of color was a stain on them. That many resisted the change to a more racially equal society was both evil and brought needless pain and shame into the world. Today the same is true of many material inequalities, which persist despite the fact that billions of people could see their lives immeasurably improved and we have the wealth to help them. When we choose not to do so despite being capable that constitutes an abnegation of our moral duties. In our current moment, when inequality is once more skyrocketing to levels not seen since the Gilded Age and many people are enduring high levels of anxiety brought about by pandemic and recession, it is time for liberals to once again ask ourselves how much more some lives should be worth than others.