Let's Wreck Some Norms and Take the Court Down a Peg

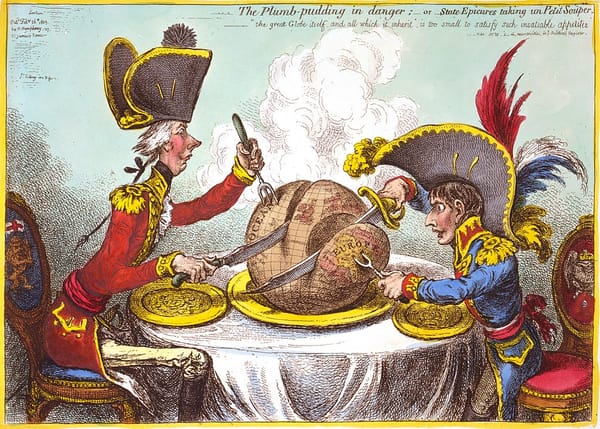

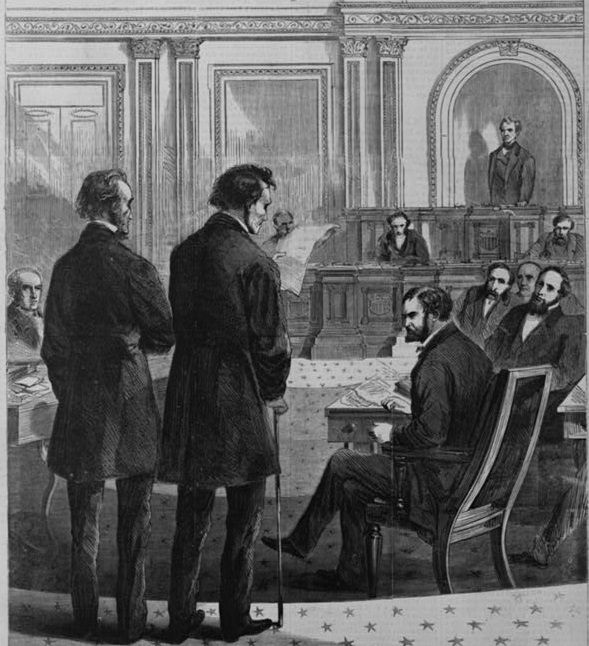

It may be difficult to believe today, but Congress was once a force to be reckoned with. The pinnacle of this, of course, was Reconstruction, during which Congress regularly overrode the president’s veto and even impeached one for the first time. Most significantly, the Reconstruction Congress regularly put the Supreme Court in its place. When Congress worried that the Court was going to use a case brought by a southern printer to end martial law in the former Confederacy, it stripped the Court of jurisdiction to hear that case. It changed the size of the Court three times, first expanding it to ten justices, then shrinking it to seven, before finally expanding it back to the original nine.

The Reconstruction Congress was exceptional in its assertiveness, but Congress in general used to have some fire in it. Unfortunately, it has been more or less defeated by the political and institutional developments of the 20th century. Never mind stripping jurisdiction or changing the size of the Court, the current Congress cannot even get a justice to show up for a hearing. Chief Justice John Roberts felt perfectly at ease rejecting an invitation to speak before the Senate Judiciary Committee. More than that, he spoke down to the chair of the committee, smugly lecturing him on the importance of “separation of powers” and “judicial independence” to justify his decision to “respectfully decline.” He gave every indication that he considers himself the adult and teacher, and elected officials the children and students. Roberts is not mad, merely disappointed that Senator Durbin attempted to get a sitting Chief Justice to testify before his committee.

Roberts will face no repercussions for his brazen contempt for Congress. The elected branches have shown time and again that they won’t take serious action against the Court, so why should Roberts believe this time would be different? Forget removing federal judges—an impossibly high hurdle anyway—simply passing legislation to outlaw the kind of corrupt behavior Justice Thomas alone has engaged in is frustratingly difficult.

Roberts knows that under the current arrangement, the nine justice Court is protected by existing institutional norms. His attempt to treat the rarity of Chief Justice testimony before Congress as evidence that it should be rare is an example of how such norms get set in the first place.

Since Donald Trump’s victory in 2016, liberals have adopted far too conservative a rhetorical posture towards institutional norms. Liberals should not be in favor of preserving norms per se. The norms that we ought to care about are the ones that serve the project of advancing liberal ideals. We did not establish the republican form of government, abolish slavery, and build the modern welfare state by politely adhering to institutional norms. Lincoln and his party were quite prepared to buck the Supreme Court and overturn the established institutional interpretations of the Constitution in order to grind slavery out of existence. Labor and civil rights activists engaged in aggressive, direct confrontation in order to apply pressure.

For the most part, the norms flouted by Trump were good ones worth protecting. Indeed some, like those around conflicts of interest, ought to be formalized into actual laws. Others, like the rules of decorum and diplomacy, are important but likely not codifiable. It’s easy to overlook their value, but just as we wouldn’t want the Federal Reserve Chairman posting all-caps panicked tweets about the state of the economy, neither should we want the commander-in-chief of the world’s largest military to be casually threatening world leaders on social media.

Norms that respect an independent judiciary—no more and no less than norms of an independent civil service—are a valuable component of a functional liberal democracy. Judicial independence is not the same as judicial supremacy, however. While liberals ought to care about human rights and the rule of law, judicial review is not necessary for either. Great Britain and Australia have been no more lawless than the United States in the last 245 years, and they have had firmly entrenched parliamentary supremacy for that entire period. We must dispense with the idea that a panel of judges weighing in on the lawfulness of legislation is a pivotal mechanism in the maintenance of a liberal legal order.

Judicial supremacy has no more merit as an ideal than the old 18th century notion of enlightened despotism. But it can be agonizing to discuss what we might do to unseat the Supreme Court from the top of our system when the procedures that hamstring our elected branches remain in place and the norms that protect the Court appear so unbreakable.

But the American system can change and has been changed before. What we call “norms” are mostly the result of previous conflicts. Each fresh conflict raises the possibility of revisiting these norms or establishing new ones. From the vantage point of the late 19th century, the federal executive branch that we have today seemed unobtainable. But we did obtain it.

There is no telling how long it might take to find the right political moment to pursue fundamental reforms of the court system. But the difficulty of the task and the uncertainty of the timeframe should not deter us from affirming its necessity and putting pressure on our elected officials to pursue it.

What follows will be an analysis of our present dysfunction, followed by a practical program for surmounting it.

Our supermajoritarian legislative process

The Court has not insulated itself with norms of deference because of the logical merit of doing so, but because it has intrinsic advantages over Congress as an institution—advantages that were cemented as the federal government took shape over the last century.

In short, the Court’s advantage is not really its own strength, but rather reflects the weakness of the federal legislative process. So long as nothing is done to create greater parity between the institutions, the status quo will continue.

We will probably never have another Congress as powerful as the Reconstruction one, because Congress can do very little alone. A congressional supremacy akin to the parliamentary supremacy of other countries is forever out of reach. With significant changes to our system, we might be able to get legislative supremacy, but the president would always be deeply involved, and the legislative process would always be cumbersome.

This is a problem, because legislation does not defend itself from misreading, misapplication, or being struck down—institutions do. Legislation passed by Parliament is supreme in the UK not because the rules say it should be so, but because of the demonstrated strength of Parliament as an institution. By the same token, we have an imperial presidency and judicial supremacy because of the demonstrated weakness of Congress.

In some ways, the very features of our legislative process that make it so difficult to defend also make it more suitable to have as the highest level of authority in our system. For even without the filibuster, it has a supermajoritarian bias.

Different constituencies elect the House, the Senate, and the president. This naturally creates divergence in the goals each pursues. But the overlap in constituencies, which is significant, doesn’t necessarily provide a countervailing pull towards cooperation either. Instead, it turns each part of the trifecta into rivals in a competition to distinguish themselves before the same audience. Another factor in the system as it exists today is that every elected official is just as beholden to a majority of their primary voters as they are to a majority of their general election voters, further broadening who they must take into account to stay in office. Finally, the different term lengths, and the president’s term limit, means that each elected official is operating on very different time horizons.

In practice this means that the support of a majority of voting Americans is rarely enough to get a bill passed and signed into law. Even a supermajority may not be enough for Senators willing to gamble that the political calculus will have changed by the time they are up for election. And, of course, the filibuster was established to give Senators that sort of breathing room; it allows members of the majority party to pin the blame for inaction on the minority party.

The filibuster should be done away with; we should not allow those Senators that breathing room. But even without it, the legislative process will only become somewhat less supermajoritarian. So long as the basic structures remain in place, it will never be simply majoritarian. And from a certain point of view, perhaps that is a good thing. Much could be done to take advantage of this, if we truly had legislative supremacy in this country. It would be far more consistent with what James Madison, in particular, had envisioned, if the more nimble state legislatures blazed the trails that the slower, more consensus-based federal trifecta selectively followed.

The problem is that this supermajoritarian process cripples Congress in its dealings with the Court. It only takes five justices to overturn the results of this tremendous effort. The Court even decides for itself what the limits of Congress’s power to strip its jurisdiction are. Roberts invented a precedent to turn down an invitation to testify before the Judiciary Committee; had they issued a subpoena it’s quite possible four of his colleagues would have joined him to invalidate it. The barriers to action, even actions with enormous reverberations across our system, is shockingly low for the Court. And so long as they have no reason to fear a response from the elected branches, they will stand at the top of the federal system.

In order to take the Court down a peg, drastic and politically difficult reform is necessary.

A plan of action

The Supreme Court, and state supreme courts following in its footsteps, became much more active in the 20th century than they had been in the 19th. But far more transformational than this was the birth of the new executive branch.

America’s administrative apparatus lagged behind its European peers. Again, precisely because of the issues described above, it took over a half a century before advocates for reform made tangible progress. And then, almost all at once, with the New Deal, an enormous and powerful executive branch sprung into existence. To say this development overturned many of the then-established norms of our political order would be an understatement.

All of this is to say that while reforming the judiciary is unlikely today, it is not unlikely if we expand the time horizon we are willing to consider. It falls on us to continue pressing for reform here and now, but we should accept that it may end up being our children who get to reap the benefits of that work.

What follows is a program for reform that is quite comprehensive. Some one or two of them are obviously more likely to go through than the whole package, but I believe that if legislative supremacy is the goal—and it should be—the entire program is worth struggling for.

Right now, five of nine individuals—who may stay in office until they die if they so choose—have the power to drastically reshape our political system. The timing in which just one of them dies, relative to who happens to hold power in the White House and the Senate, can have consequences for generations. Court reform should aim to water down the impact of any single justice and increase the predictability of appointments.

To that end, every presidential term ought to come with one appointment to the Supreme Court, whether or not any of the previous justices have left office. This would slowly expand the Court, of course, but it would do so in a way that isn’t clearly to the advantage of any one party, since it would be tied to future election results, not current officeholders.

Another way of watering down the strength of individual justices would be to increase the strength of circuit court judges. They are no less qualified in their knowledge of the law than the justices. Therefore, we ought to create a process by which a majority of circuit court judges (across all the circuit courts) can call for a special panel to review a recent Supreme Court decision. This would work similar to how en banc sessions work within circuit courts today.

Taken together, these reforms would shift case law in the direction of reflecting a consensus among the federal judiciary, rather than a simple majority of the nine top judges. This alone would make it more predictable and less prone to drastic, nakedly political action. It would balance the scales of institutional politics with the elected branches somewhat.

To that end specifically, legislation ought to be passed setting rules around disclosure, conflict of interest, and recusal, with financial penalties and jail time for breaking them, and an independent body to adjudicate them so that judges are not overseeing their colleagues. This would firmly establish that no branch of government, not even members of the top court, are above the law—law produced by the elected branches.

The Supreme Court also should be stripped of the jurisdiction to hear cases about its own organization, jurisdiction, or oversight. And finally, legislation ought to be written specifically stating that statutory interpretations of the Constitution have more authority than case law—with a provision stripping the Supreme Court of jurisdiction to review it. Even with all of these reforms, the courts would still be a powerful force in our system, given the difficulty of the legislative process and the natural ambiguity of statutory law.

The judiciary will only become weaker, however, if we make the legislature stronger. If we’re going to increase the importance of the legislative process, then there are several aspects of Congress and our current party system that could use serious alterations.

The primary system both cements our two-at-most party system, and leaves us with weak husks of parties, whose members are easily captured by well-funded interests. We need federal legislation banning state or local governments from regulating political party nomination systems as a first move towards ending the primary system entirely. Strong parties are a necessary vehicle for organizing legislative politics; they act like unions among politicians in order to draw the best overall bargain from interest groups in the party coalition.

However, strong parties need a competitive environment even more than weak ones. To that end, we should pass a federal law turning every state into a single House district each under a party-list proportional representation scheme. This is a separate matter from how many seats are apportioned to each state, the total of which also ought to be put on a fixed seat-to-population ratio rule. Finally, we ought to invest much more in congressional staffing, including permanent staff for the committees and other institutional positions. Taken together, this second set of reforms would address much of the dysfunction that the polarization of the last thirty years has wrought on the legislative process, allowing the elected branches to better fulfill their roles.

Unflinching support for legislative supremacy

The Roberts Court holds elected officials and their agents in unhidden contempt; indeed Roberts’ letter is just the most recent announcement of this fact, and not even the most brazen. By contrast, the childishly naive characterization they offer of judges and the role they perform would be embarrassing among adults with more than an eighth grade civics education, were it not so nakedly self-serving.

Georgetown University Professor of Law Joshua Chafetz discusses “the way in which the justices portray the roles of various actors, including themselves.”

Administrative agencies are unaccountable behemoths that threaten to destroy republican self-government; (. . .)Congress is simply trying to pass the buck so as to avoid responsibility for tough decisions. (. . .)Of course, the justices never describe the motivations of their own institution: they simply describe the principles that they think should limit the other institutions, thereby implicitly holding themselves out as impartial, apolitical appliers of those principles.

No institution, elected or unelected, has a monopoly on vice, and neither the Supreme Court in particular nor judges in general have a monopoly on virtue. When he leaves the judiciary out of his analysis entirely and focuses on the vices of the other branches, or when he specifically sings special praise to the role of judges without reference to why we ought to believe them more capable of high-mindedness than administrators, Roberts is being naive at best, and more likely self serving—but certainly not realistic.

The attitude that the Court has towards itself, is little more valid than the longing for an enlightened despot. What difference is there between the credentialism of judicial supremacists and the autocrats who speak of the necessity of kings who are groomed for office? What difference is there between the version of judicial independence which posits judges completely unmoved by politics, and the popular image of the dictator as one who can act unhindered by legislative squabbling?

As an ideal, judicial supremacy, where the highest court gets the final say in any dispute, is equal in its folly to its 18th century autocratic counterpart. Legislative supremacy is not only more morally defensible, it is more pragmatic. In a modern, commercial society, especially a very wealthy one, the capacity for disrupting a political order is spread very broadly in the population. Representative institutions allow officials elected by the many interests of society to negotiate on behalf of those interests, creating a greater chance that the end result will not sow strife.

Judicial independence is important, but no more so than administrative independence. “Independence” should neither mean the absence of accountability nor indifference to the authority of elected officials. It is a difficult balancing act where implementers of the law are given a bit of arms-length space from direct partisan contestation, but are still ultimately accountable to the elected branches.

We don’t have that in America. But we could. And we should.

Featured image is Thaddeus Stevens and John A. Bingham before the Senate, by Theodore Russel Davis