Censorship, Social Sanctions, and Access to Audiences

Over the last few weeks, issues ostensibly about freedom of speech once again made headlines. Unfortunately, these debates seem plagued by conceptual brittleness. Classically, “freedom of speech” refers to freedom from state-enforced censorship, and despite what the current state of the “free speech” debate might lead one to think, the threat of such censorship is still very much with us. There is SESTA/FOSTA, retaliation against the speech of prisoners and parolees, the use of unidentified federal forces against protesters, and the exporting of Chinese censorship through global corporations, to name only a few.

The primary focus of the current “free speech” debate are not threats of this sort at all, but the threat of social sanction. I do not think we can make a principled case for a generalized freedom from social sanction. Freedom of association necessarily means freedom of disassociation, and the combination with freedom of speech means that people are able to argue for casting out particular members of an association. To come together to express shared values or pursue a goal can only work if one is able to cast out those whose participation is at odds with those values or that goal. But this is not a brief for unbridled freedom of association; any American should be familiar with what the right to refuse service, for example, has historically meant in practice. Yet the typical limitations on freedom of association, used to soften the hard edges of disassociation, are rarely raised in the context of the “free speech” debate.

Distinct from both of these considerations is the question of how open our media ecosystem is. “Openness” is here understood as the degree to which ordinary individuals have a reasonable chance of being heard. In the age of the Internet, social media, and the smartphone, many messages can reach the broader public even in a society with strict state censorship and harsh social sanctions. If we believe that it is important to be able to get ideas out there, even if one must take risks in order to do so, then having a media ecosystem that is more rather than less open is crucial.

These, then, are three distinct questions that the current debate over “free speech” runs together in a sloppy fashion: is the state engaging in acts of censorship? Are social sanctions against speech or beliefs too harsh? Is our media ecosystem sufficiently open? Failure to disentangle these questions has resulted in the current abysmal state of the conversation.

The long arm of the law

Once upon a time, if you wanted to publish a book, you had to go through a publisher. Even if you wanted to print a lot of pamphlets to distribute, you had to go to someone who had a printer. In other words getting people to hear what you had to say required a significant capital investment for most of history. Despite this relatively high barrier to entry, the early modern advocates of freedom of speech did not formulate that ideal to include the permissiveness of printers. If a liberal or a civic-republican—or, later, a socialist or labor organizer—was refused by the big printers, there were always smaller, independent ones. Even fairly nascent movements were usually able to pool their resources to ensure they had a printer sympathetic to them. Freedom of association and a robust commercial sphere offered numerous potential avenues to publication. No one printer had absolute veto power.

But governments do. When the state bans your book, your options are drastically reduced. You can petition the designated state official, if there is one and if they’ll let you. You can take the state to court in the hopes that the judiciary will side with you, but before the First Amendment and especially before late 20th century First Amendment case law, that was highly unlikely. If the law allowed for an official censor, odds were the judges would find no cause to quarrel. Nor do court cases come cheap to the litigator, then or now.

Those of us who live in 21st century liberal democracies are all too likely to forget that the state has other, far less polite censorship methods at its disposal than issuing an injunction or a fine. In contemporary Iran, blogger Hossein Derakshan spent six years in prison for his views. Historically, the removal of limbs was not off the table, nor was the death penalty. Nor should distance in time or space lull us into complacency, with SESTA/FOSTA on the books and federal forces in Portland assaulting protesters before stuffing them into unmarked vehicles. To say nothing of the Trump Administration’s varied and aggressive actions towards the press.

Contemporary anti-terrorism laws and agencies have frequently targeted “dangerous” speech. In 2014 France passed a law criminalizing “apologies for terrorism” and by 2015 they were using it to jail muslims who praised the attack on Charlie Hebdo that year. The international community had rallied around the magazine to support its right to publish cartoons of Muhammed, however offensive, yet the freedom of Muslims to speak their opinion—however hateful we may find that opinion—was not only curtailed, it was curtailed through prison time. And we should never forget that even with the polite veneer of a court system in a democracy, such proceedings always rest on the threat of violence.

That is why we should not allow other, broader concerns to be gerrymandered into the legal ideal of freedom of speech. Even here in America we are simply lucky to have obtained the First Amendment jurisprudence we did as recently as the late 20th century. At the dawn of that century, the 1918 Sedition Act was used to gag newspapers from reporting the flu that was ravaging the country, with devastating effects. Freedom of speech, understood as nothing more or less than freedom from state censorship, still requires a zealous defense. Such a defense calls for conceptual clarity and careful distinctions between this ideal and others, however closely related they may be.

Employment in America

Though it is nowhere enshrined in the American Constitution, and therefore gets substantially less play in public debates, freedom of association as an ideal is in many ways more constitutive of liberal society than freedom of speech. Whether or not a hairdresser can weigh in on the public debate around statue-smashing is likely a less pressing concern than whether they can leave their current employer and find a new one, or start a hair salon themselves as sole proprietors. Even the right to preach in public may be less valuable to the religious than the right to form churches.

The outcomes of freedom of association are not neutral or egalitarian, however. Not everyone is in a position to organize in the first place. The difference in political muscle between the organized and disorganized (regardless of whether some of the latter had been in a position to get organized) is also palpable. Most importantly for the present discussion, some people are put in a position to put the livelihood and comfort of other people in jeopardy.

In addition to this asymmetry of social power is an asymmetry of wealth. No one can credibly worry about the fate of Bari Weiss or James Bennett, but there are people in this country who cannot afford to lose their job. But this isn’t a problem that began with “cancel culture” and a large number of remedies have been discussed, proposed, and implemented in many times and places. The twin vices of myopia about our moment and provincialism about the American context have largely kept these remedies out of the discussion.

The left has criticized the power of employers over employees for as long as there has been a left. Unionization and collective bargaining is one way that reformers sought to equalize the power between them. America has taken a number of measures to weaken unions, while several European nations have taken measures to strengthen them.

America is also fairly unique in its widespread enactment of at-will employment, a fact long criticized by leftists as well as by liberals like Elizabeth Anderson. Critics of “cancel culture” warn that ordinary people risk losing their jobs if they fail to meet standards met by intrusive moralists. Such critics may find this from Anderson to be of interest:

The Industrial Revolution moved the primary site of paid work from the household to the factory. In principle, this could have been a liberating moment, insofar as it opened the possibility of separating the governance of the workplace from the governance of the home. Yet industrial employers retained their legal entitlement to govern their employees’ domestic lives. In the early twentieth century, the Ford Motor Company established a Sociological Department, dedicated to inspecting employees’ homes unannounced, to ensure that they were leading orderly lives. Workers were eligible for Ford’s famous $5 daily wage only if they kept their homes clean, ate diets deemed healthy, abstained from drinking, used the bathtub appropriately, did not take in boarders, avoided spending too much on foreign relatives, and were assimilated to American cultural norms.

To my knowledge, Zaid Jilani is the only one who has brought up at-will employment in the context of the “cancel culture” debate. This isn’t some abstract consideration; most of the world regulates employment relationships differently, and Montana does as well. All of these alterations to freedom of association carry trade-offs, of course. Making it harder to fire people, whether through stronger unions and collective bargaining or abandoning at will employment, means making it harder to fire office workers that make the workplace hostile, professional drivers who drive while intoxicated, and people who, willfully or not, simply don’t contribute enough to their company to be worth their paycheck.

If that doesn’t sit well with critics of “cancel culture,” we can opt instead to push for more generous and more universal social safety nets, making the material downside of losing one’s job much less dangerous. However one chooses to go about it, mitigating the material downsides to freedom of association is the most direct way to address the way disassociation gets turned into a tool of social sanctioning. It is therefore very odd that so much energy is expended attempting to persuade the mob, however large, to have more self-control, when that simply does not scale.

Take, for example, Kat Rosenfield’s essay in Arc Digital on the woman who told the police “An African-American man is threatening me and my dog.” Rosenfield believes that what the woman did was horrible, calling it not “just an execrable display by someone who was already in the wrong, but a power play that extends a horrifying and violent history of white people reporting innocent black men to the police for non- (or fabricated) offenses.” Still, Rosenfield wonders when enough is enough, especially for targets less deserving than this one:

And yet, there must be a point at which the correction does become “over-.” Was it when the police acknowledged the incident? When Amy deleted her social media accounts? When her employer announced that she’d been suspended? When the cocker spaniel rescue organization announced that it’d taken back her dog? If we allow that it was correct for one person to alert the rescue to the video, do we draw a line at five people? Fifty?

Rosenfield is trying to ask when it is “enough” in principle, as if a limiting principle could truly be the guide here. But fifty people is a very small fraction of the audience reached by a highly viral story. Rather than hoping for self-discipline, or reasoned calculation, or the better angels of our nature, critics of “cancel culture” really ought to be thinking structurally. As long as employees can become PR liabilities for their employers, and employers have the power to fire them, they will do so.

To focus so intensely on the New York Times or Vox staffing disputes is to invite the interpretation that “cancel culture” critics care primarily about intra-elite competition. Drawing proper distinctions between freedom of speech and the dangers of social sanctions in a free society can help clarify their criticism and shift the focus to the truly vulnerable.

Can’t stop the signal

Our third question concerns the openness of our media ecosystem. But what does “open” mean in this context?

The most open media ecosystem will offer broad access to potential audiences. A “potential audience,” as the term implies, is a possibility. This is, quite simply, the probability of obtaining an audience for a public statement. In a media ecosystem that offers broad access to potential audiences, the typical person is capable of making a public statement with a high chance of obtaining an audience while incurring minimal cost.

It is important to emphasize that the distribution of actual audiences will always be highly unequal. This is a well established finding in network science; as Clay Shirky once put it, “freedom of choice makes stars inevitable.” This is why potential audience is the appropriate unit of measure for assessing the relative openness and egalitarianism of a particular media ecosystem. Though the actual audience distribution is extremely clustered around a small percentage of players, there is a long tail in which nearly all players have a fairly equal chance of having some specific public statement “go viral,” however small that chance might be.

But let’s step back from the principles for a moment and look at specific systems. At one extreme, for the vast majority of history, humanity had neither the printing press nor paper. The materials for writing were scarce and each piece of writing could only be copied by hand. As a result, literacy remained in the low single digits—either writing or reading were possible only among a small priestly caste or nobility. Formal censorship of anything but oral speech is hardly even necessary in such an environment; the closedness of the media ecosystem precludes politically dangerous speech outside of a small circle of people who all know one another.

Of course, most people don’t compare our current situation with the media ecosystem of the Middle Ages or early modernity. Most American media critics have the 20th century institutional media model in mind. But the midcentury press was radically less open than our current media ecosystem. High capital costs, the tightly regulated broadcast licensing system, and mass markets created a small number of large players and what was arguably a media cartel. Just as a shortfall of freedom of speech in the 1918 pandemic contributed to that tragedy, so too the lack of openness in 1968 likely played a role in glossing over a pandemic that ultimately led to 100,000 American deaths.

Today, the barrier for entry is remarkably low. Almost anyone is in a position to have a social media account, and any social media posting has the potential to go viral. Moreover, if we shrink the size of the potential audience under consideration, the probability increases dramatically. We tend to underestimate how hard it was for most people to achieve an audience of hundreds or even dozens before the Internet. A typical community theater might have considered audiences of such sizes a sign of great success! Now a moderately motivated social media user has a high likelihood of achieving it.

“Private” Facebook groups, discussion forums, and chats, moreover, form publics, small stages on which one can speak and be heard as much as listen and converse. And of course it is easier than ever to launch an independent publication, from Jacobin, to The Daily Caller, to Vox, to our own Liberal Currents. The broad access to potential audiences means that even if a link that the creators of these publications posts to social media do not go viral, any of the handful of people who may share it can have their post go viral. A widely equal probability of obtaining an audience translates into more broadly held power to determine which publications gain actual audiences.

“The Internet promised to take power away from media gatekeepers and make censorship near-impossible,” blogger Scott Alexander once recounted.

In discussing the many ways in which this promise has admittedly failed, we tend to overlook the degree to which it’s succeeded. One of the most common historical tropes is “local government and/or lynch mob destroys marginalized group’s printing press to prevent them from spreading their ideas”. The Internet has since made people basically uncensorable, not for lack of trying.

Unlike freedom of speech, which is a purely legal matter, there is obviously an enormous technological component to building an open media ecosystem. But it is not only technological. Many institutions, from ICANN to Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to corporate behemoths like Google and Amazon, govern the operation of the Internet. The information transfer mechanisms that power the Internet are protocols; while certainly technological, their adoption by important stakeholders is as much a social matter as the adoption of diplomatic protocols between nations.

Threats to the openness of our media ecosystem abound as well. Some of the very things that have made our media ecosystem more open create structural threats to that openness. It is now easier than ever for a publicly unknown person who is only interacting with a small group of friends online to go massively viral, specifically because of gigantic social media platforms. But the very concentration that makes such potential virality possible also puts most online content under the governance of a handful of corporations.

Moreover, most of us would agree that those corporations should engage in content moderation of some kind; few would deny that fighting fraud and spam are a valuable service, for example. The more aggressive measures that platforms have taken during the pandemic are more controversial but still quite defensible given the situation. Speaking for myself, I find the basic fact that such large entities have such disproportionate power over the openness of our ecosystem more concerning than any specific example I’ve seen of their supposed overreach.

I think we should be investing in technologies and tech industry ecosystems that are more decentralized and thus less vulnerable to single points of failure. But conflating this challenge with the struggle against state censorship or the potential harshness of social sanctions only muddies the water.

The three matters considered

One recurring theme in the struggle for liberty is that its defenders too often imagine a free world to be far more pristine and peaceful than any world ever is. As a corrective against this, Sean Illing suggests that “all the excesses [and] the speech policing isn’t a short-circuiting of a free society but its outcome.” Indeed, one of the things that people will do when they are free to speak and have access to audiences who will listen, is to accuse other people of misdeeds and call for them to be socially sanctioned.

Facebook is not only a single point of failure whose arbitrary choices can impact the openness of our media ecosystem; they also receive pressure from activists who wish to enlist Facebook as an arm of social sanction. It may be that developments in America parallel those in China not by adopting our own “Great Firewall” but because we both have our “human flesh search engines” engaging in distributed social sanction. Recall Rosenfield wondering if fifty people making the call to get someone punished is more than enough. In a wide open media ecosystem, it only takes one person to widely distribute someone’s personal information. It only takes a fraction of a fraction of a percent of a viral story’s audience to inundate someone’s employer with calls or to fill someone’s day with messages that range from unpleasant hostility to overt threats.

Freedom of speech, freedom of association, and open media ecosystems are important ideals but they have real costs, especially in combination. If what we want is a frank assessment of those costs and an intelligent conversation on what to do about them, we will need to be able to consider each with clarity. That means understanding them both as distinct considerations and as considerations that interact in complex ways.

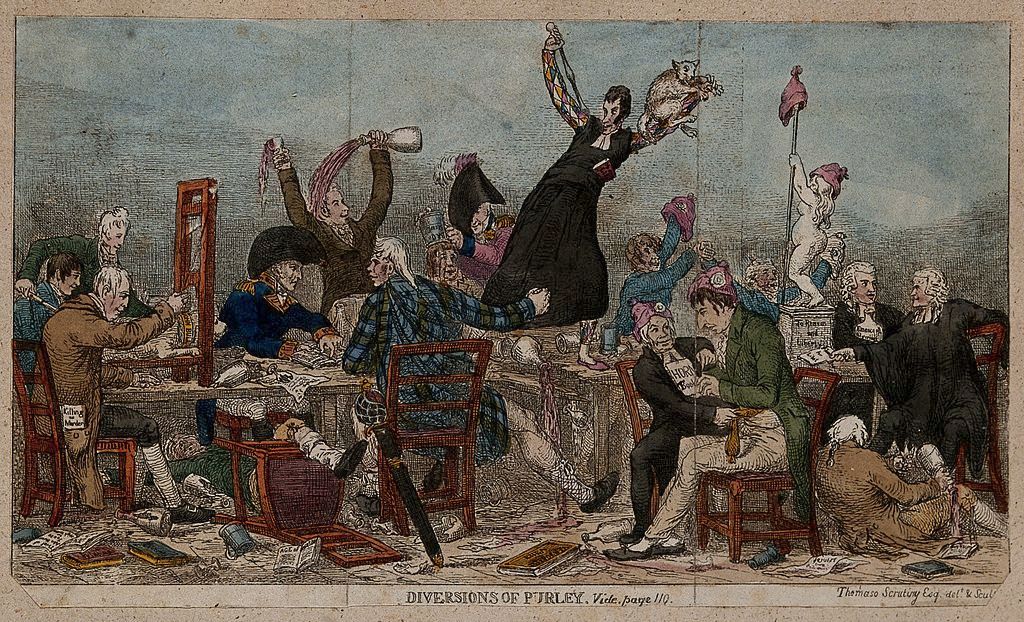

Featured Image is A rowdy dinner of British political radicals at John Horne Tooke’s house in Wimbledon